The Pitfalls of Teleological History

Herbert Butterfield, and the Whig Interpretation of History -

At the end of last week’s post, I said this week would get into contingency and determinism, as part of a discussion of why it’s difficult to derive general laws from history. This post on Whig history, however, grew into something which I think ought to stand on its own.

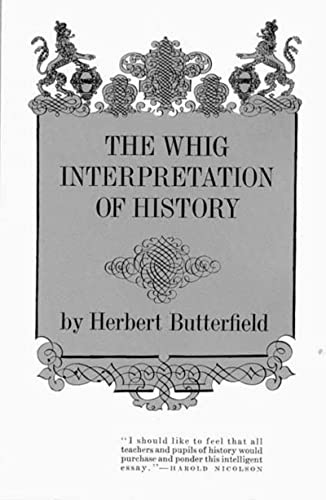

Last week, we mentioned Whig history, dating back to the 19th century and associated with English historians such as Macaulay, who charted the rise of modern Great Britain. Whig history was famously1 dethroned in 1931 by Herbert Butterfield’s short book The Whig Interpretation of History. Butterfield critiqued historical narratives that saw the rise of the modern world as inherently progressive, and essentially inevitable. In particular, Butterfield focused on the Reformation, Protestantism, and all the political struggles of the Tories and the Whigs in the early modern era. These historical narratives had a sharp trend of “dividing the world into the friends and enemies of progress”2, with everyone playing their proper role one one side or the other of a historical contest that would eventually lead to the modern world:

“The total result of this method is to impose a certain form upon the whole historical story, and to produce a scheme of general history which is bound to converge beautifully upon the present – all demonstrating throughout the ages the workings of an obvious principle of progress, of which the Protestants and whigs have been the perennial allies while Catholics and tories have perpetually formed obstruction. A caricature of this result is to be seen in a popular view that is still not quite eradicated: the view that the Middle Ages represented a period of darkness when man was kept tongue-tied by authority – a period against which the Renaissance was the reaction and the Reformation the great rebellion.

The whig historian stands on the summit of the twentieth century, and organized his scheme of history from the point of view of his own day; and he is a subtle man to overturn from his mountain-top where he can fortify himself with plausible argument.”3

We have here a fair encapsulation of a still popular today “just-so” story of the rise of the modern world; the Renaissance and Reformation inaugurating a series of positive changes that, despite a few bumps along the way, eventually created the modern secular, capitalist, and individualist world. Butterfield’s contention is not over the particular merits of said world, but with how it essentially reasons backwards from the present, drawing lines of interpretation and meaning based on the end result, and the preferences of the narrator.

I think it’s fair to say that, while most historians today reject Whig history, something of this notion of progress and change in the modern world remains. We still sometimes use “medieval” for primitive or unsophisticated, we talk of the “arc of history bending towards justice,”4 and of people needing to get on the “right side of history” on moral and social issues.

In fact, even when we reject this notion of ever expanding progress, we’re still applying the same overall teleological lens, just with the polarity reversed. A reactionary view of history that sees this narrative as bad (siding with the Catholics and Tories instead of Luther and the Whigs) is just switching sides on the historical “teams” that Butterfield describes. In Historian’s Fallacies, David Hackett Fischer discusses Whig history and the possibility of:

“an anti-Whig history which commits the same fallacy in an inverted form. Examples include the later works of Henry Cabot Lodge and Henry and Brooks Adams…For these gentlemen, history was…a steady spiral running downward toward the left, and culminating in some dark catastrophe.”5

For Butterfield, the underlying problem is essentially that of presentism; writing history due to present concerns, and being all-too conscious of where the story is supposed to end up. Historical agents and events are given moral weight and judged not so much on their merits, but on whether they happen to fall on the “right” or “wrong” side of history. Also, agents and events are viewed with an after-the-fact lens, and not evaluated in the context of how they saw themselves in their own day. Martin Luther did not set out to create the modern secular world. He didn’t even initially attempt to create a Protestant world.

Interestingly, Butterfield notes this temptation is almost inherent in history, and that the more we condense and shorten our narratives, flattening out details and context, the more likely we are to stray into Whig territory:

“The truth is that there is a tendency for all history to veer over into whig history, and this is not sufficiently explained if we merely ascribe it to the prevalence and persistence of a traditional interpretation. There is a magnet forever pulling at our minds, unless we have found the way to counteract it; and it may be said that if we are merely honest, if we are not also carefully self-critical. we tend easily to be deflected by a first fundamental fallacy. And though this may even apply in a subtle way to the detailed work of the historical specialist, it comes into action with increasing effect the moment any given subject has left the hands of the student in research; for the more we are discussing and not merely inquiring, the more we are making inferences instead of researches, then the more whig our history becomes if we have not severely repressed our original error; indeed all history must tend to become more whig in proportion as it becomes more abridged.”6

That last line is fascinating to me. The more a story is shortened, the more context and nuance is cut out. All that remains is a straight (or nearly) straight line of apparent causation from A to B, making it all the easier to assume that A must have led to B, and cutting off the possibility of imagining other outcomes or influences. In the popular imagination, very complicated events become fuzzy trends going up (or down). Indeed, insofar as Whig history survives as a term today in popular discourse, it tends to simply mean “the modern world has progressed into some ‘better’ state” regardless of whether there is a specific teleological arc at work. One could believe the modern world to be better off today than in the past, without it being an iron law of history that the world must get better over time.

Butterfield’s solution to Whig history -

There is a very fine line to walk between historical presentism (reading the present back into the past), and the core mission of history as an inquiry into understanding how the world came to be what it was. Butterfield himself is not unaware of this difficulty of merging past and present, and he recognizes that “there may be a sense in which this is unobjectionable if its implications are carefully considered, and there may be a sense in which it is inescapable,”7 since we can’t ever truly remove ourselves from our own contexts.

But as much as possible, the solution for Butterfield is similar to that of R.G. Collingwood; the historian must believe:

“that we can in some degree enter into minds that are unlike our own. If this belief were unfounded it would seem that men must be forever locked away from one another, and all generations must be regarded as a world and a law unto themselves.”8

Many historical questions are animated by present concerns, although sometimes academic historians deliberately attempt to divorce their research from any present issues in a quest for “pure research.” One can certainly study the past for the sake of its own inherent interest and worth, but if historians don’t have anything to say about how the past creates the present, then amateurs, pundits, and politicians are going to fill that space for them, in ways that historians probably aren’t going to like. The historian has to be willing to write with an eye on the present, while also remembering that understanding the present is best served by taking the past on its own terms as completely as possible.

Taking the past on its own terms -

The historian has the advantage of his subject, in that he already knows the end of the story. Individuals in the past were often confused, operating on incomplete or inaccurate information, and didn’t know the results of their actions ahead of time. A soldier in Napoleon’s Grande Armée had no way of knowing the outcome of the battle, or the next month’s campaign, and which factors in the battle would be most important. But the historian compiling the evidence after the fact is better able to weave together a complete picture out of messy information, and draw the necessary dots to tell a meaningful story about what happened and why. It’s not all that different from what happens when you watch a good mystery movie for the second time, as previously overlooked details jump out with new meaning and significance. The ability to work backwards from the end allows the historian to separate out the truly important causes from the false starts. When we say that the past is creating the present, these are the variables we’re looking for.

There’s just one problem with this ability to see an event with greater clarity and context, which is precisely the fact that our historical actors didn’t have that clarity and context themselves. The fact that we know the end result actually increases the difficulty of understanding what it was like for our historical actors to live through the event in the first place. Our historical actors didn’t know what was going to happen; they had to consider all possible outcomes, including the ones that the historian (in hindsight) knows to be false or unimportant. At the start of a war, a general has no knowledge of the battle which future writers will criticize him for not reinforcing sufficiently, and a political leader doesn’t know if a painful policy intervention will be worth the political cost of angering a key constituency. There are many examples of governments spending too little to prepare for a negative event, but sometimes you simply won’t know until after the event if you were being fiscally prudent, or recklessly tight-fisted (and this outcome may simply be the result of good or bad luck). The clarity of hindsight can actually blind an observer to the true difficulty of the moment.

The historian, then, must on the one hand use his or her knowledge of the overall outcome to look for the key variables that tell the story, and yet at the same time factor in the historical actors' very ignorance of that outcome. The historian has to mentally hold the outcome in abeyance for the moment, and try to imagine what it is like to reason or act on uncertain, incomplete, or contradictory information. This takes us back to R.G. Collingwood’s emphasis on the re-enactment of past thoughts, even though those thoughts will now exist on a separate plane from their original context. A historical agent forced to make a difficult decision or attempting to invent something for the first time may actually be faring much better than others, while still ultimately failing. As a rule of thumb, I try to maintain sympathy for individuals dealing with novel problems, such as WW I generals struggling to respond to trench warfare, or seemingly bizarre attempts to mitigate sickness during historical pandemics.

In fact, sometimes historical false starts and strange experiments can be genuinely useful case-studies. We can gawk at all the failed attempts at making flying machines throughout history, or seemingly foolish scientific theories of many pre-modern philosophers. But reasoning backwards based on the premises behind plague doctor outfits, or Thales’ imagined model of the universe, can offer insight and even respect for how people attempted to understand the world based on limited information. The fact that Greek artisans might have technically been able to produce steam engines, but lacked all the necessary social, organizational, and infrastructure incentives to come up with a genuine use case for them, actually reveals quite a bit about the nature of innovation. Late medieval and early modern philosophers clung to Aristotle’s Physics and the Ptolemaic model of the solar system for too long, but less obvious to us today is that both of those philosophical systems undergirded a host of other practical and useful ideas and concepts. Galileo and Copernicus weren’t simple morality tales of innovation and progress overcoming ignorance.

Tu quoque, Butterfield? -

Butterfield’s short book did much to shift academic historians away from notions of Whig history (except again, the Marxists, who carried on with their own teleological histories for several more decades). But, in the spirit of being fair to Butterfield’s own target, we ought to note that The Whig Interpretation of History may suffer from the very act of abridgment that Butterfield himself warns about. For the Whig history that Butterfield criticized never actually existed as a concrete school of historical thought; there was no self-labeled “Whig historiography” the way one could refer to Rankean or Marxist historiography. As William Cronen, a former president of the American Historical Association noted:

What exactly this curious phrase [whig interpretation of history] meant was not immediately clear, since it had never before appeared in print. As Carl Becker rather grumpily remarked in one of the very few reviews anyone ever wrote about the book—the American Historical Review gave it no notice at all—"The phrase may have an accepted meaning in England; but, so far as I know, it has none elsewhere. In fact, I do not recall ever having heard the phrase before." Worse still, Butterfield did not bother to cite any of the "Whig historians" he criticized. Thirty years later, E. H. Carr famously joked that although the book "denounced the Whig interpretation over some 130 pages, it did not . . . name a single Whig except [Charles James] Fox, who was no historian, or a single historian save [Lord] Acton, who was no Whig."

In fairness to Butterfield, David Hackett Fischer is slightly kinder than E.H. Carr, and notes that Butterfield does in fact manage to quote one genuine Whiggish historian. 9

Yet, despite there not being a definitive school of Whig historians, Butterfield’s overall charge and the tenor of his critique rings too true to simply dismiss. There was a general trend of viewing the rise of the modern world as a triumphant progress, and it was hard to avoid the temptation to see the roots of the Victorian Britain lying back far in the medieval past.

That same issue of abridgement creating a false illusion of causality may be at work here. Popular notions of progress and simplified historical narratives created a notion of Whig history even without a self-professed school of Whig historians, and in trying to pin down such a nebulous and wide-ranging sensibility, Butterfield had to do his own act of cutting the historical record down to shape and size. I’ll chose to take this as a reminder to be cautious about applying historical labels onto the past, and to realize that their utility may have limits. Maps are only representations, after all.

I realize I keep saying “famously” in reference to various historiographical events and figures that, outside of academics and enthusiasts such as myself, are basically unheard of. I similarly have a hard time remembering that Samuel Eliott Morrison, who wrote the official history of the U.S. Navy during WW II, isn’t a household name. I saw him referenced so often in the WWII books that I read as a teenager that my memory takes him for granted as a noted authority that “everyone” knows.

It’s often overlooked that when Martin Luther King Jr. popularized this phrase, he was making a theological point about providence, and not a historical point about a teleological arc.

David Hackett Fisher, Historians Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought, Harper Torchbooks, 1970, 139

Fissher, Historian’s Fallacies, 281

Right- it's not just Whigs who practice "Whig History," it should always be said

This post is an antidote to history buff ignorance.