Mapping the Past: John Lewis Gaddis and "The Landscape of History"

Part four on the nature of history and why we should study it

Much thanks to everyone who has subscribed and read these first few posts, I’m very grateful for the initial reception. Please consider passing the newsletter along to anyone you think might be interested.

Last time, we looked at R.G. Collingwood’s assertion that all history is the history of thought, and that historians must “rethink” past thoughts and understand the intention put into them. Now, let’s scale the act of interpretation up beyond the individual level.

To understand what it was like to be Nelson on the deck of the Victory, or to be a medieval peasant, we have to understand the context and circumstances of a past environment, and how an individual might interact in that environment. But notice what happens when we go from a very specific individual, such as Nelson, to a more general category of persons, such as medieval peasants. We have to extrapolate from individual experiences (many different peasants), and add in data from other sources (legal texts, environmental records, archeology, folklore, art, etc.), in order to plausibly re-enact what life was like for a peasant in general, and not just a particular individual. While still essentially the same process as Collingwood’s rethinking of past thoughts, we are no longer rethinking a single individual, but are re-enacting a category of thoughts.

As we move from an individual life or event towards a broader category of individuals or actions, we find broadening opportunities for interpretation, but also increasing limitations as we lose specificity. One individual life from the middle ages may not apply very generally towards medieval life as a whole, although it may tell us something about a specific category of individuals (the life of a peasant can tell us something about peasants in general). Eleanor of Aquitaine is hardly representative of medieval life, or even of medieval female life, but she can tell us something about the life of powerful nobles and statecraft in medieval society.

(As an aside, most pre-modern histories were written about kings and nobles; and often tell us little, if anything, about everyday life. Indeed, the very fact that novelty, rarity, and excellence are most likely to gain attention means that our written historical record is full of exceptions to the rule. As with modern media’s “if it bleeds, it leads,” practice, this emphasis on the unusual can sometimes make it hard to understand the baseline norm. Historians such as Thucydides, Polybius, and Procopius all set out to tell stories that they explicitly told us were extraordinary; it would’ve been odd if they’d written intentionally dull books about politics and diplomacy in times of peace.)

Often, it’s the broader questions that we most want answers to; such as what was medieval life like in general? If we want to know the overall tenor of a time period, or other large event, then we find ourselves necessarily having to abstract and flatten as we go outwards. It’s likely that each individual experience won’t map perfectly onto that general conclusion; there will be many exceptions and qualifications.

Most of us are familiar with the general idea of feudalism (medieval nobles granting land to vassals in exchange for military service), and think of it as one of the fundamental building blocks of medieval society. Yet, as soon as you get into the details, variations across time and place will rapidly bury you in uncertainty. The classic image of feudalism derives mostly from France, but German feudalism under the Holy Roman Empire was different from Norman Feudalism grafted atop Anglo-Saxon England, which was different from Spanish frontier fiefdoms acquired during the reconquista, which was different from the political and economic dominance of city-states in Northern Italy. And, feudalism presupposes that a majority of a lord’s military power will come from vassals fulfilling oaths of services on set terms; but by the 14th century, many kings were increasingly accepting payments (essentially, taxes) from vassals in lieu of service, and using their newfound revenues to contract out for paid troops. So then, was feudalism over by the 14th century? Note that we haven’t gone anywhere near the later political usages of the term during the Enlightenment. Reddit’s r/historians forum, where academic historians answer questions from the public, has a discussion of whether feudalism even really existed in the first place.

So, a narrow and specific focus can generate a sharper picture of limited applicability, while a very broad lens can take in much larger contours, which rapidly become fuzzy when individual parts are magnified. However, this is not the only problem we find in interpreting historical information.

While past individuals could probably explain small facets of their daily lives that escape us, other features of their lives only become clear in hindsight, or by applying a much larger lens onto a problem than they had access to. If part of the answer to why Norse settlements on Greenland (organized around walrus-hunting for ivory) died out in the 15th century is Portuguese expansion into the West African ivory trade, the historian may know more about the collapse of a society than those who lived through it. And just about any pandemic from before the advent of germ-theory is going to be one where historians can supply crucial information not available to the victims.

Other times, the very nature of an event may be hard to grasp for an individual participant. Individual battle narratives are a good example of this. An individual soldier, whether in a Greek phalanx or a WWI trench, has a very limited and incomplete picture of a much larger battlespace. Almost certainly, the older “guns and trumpets” historiography which focused on generalship and grand flanking maneuvers gave an incomplete picture of a battle, and needed the corresponding “grunt in the trenches'' perspective to say something more complete about the nature of war. But when it comes to understanding these two very valid perspectives, the historian (even while lacking direct lived experience) may be better placed to interpret some facets of the event than either the General or the Private.

We seem to be lost in apparent contradictions. Along with the difficulty of clear interpretation when moving between the particular and general, can we reconcile R.G. Collingwood’s dictum that “all historical knowledge is the history of thought” with historical agents who can’t always understand aspects of the phenomena we’re supposed to be interpreting through them?

We need a map.

The Landscape of History by John Lewis Gaddis is a provocative little manifesto laying out the task and potential rewards of the study of history. The defining image and cover art of the book is Caspar David Friedrichs’ The Wanderer above a Sea of Fog (1818). In a metaphor which works on multiple levels, Gaddis asks us to imagine the historian as a wanderer looking out over a shrouded landscape. History is a foreign country waiting to be discovered by an explorer who doesn’t know what he will find. Standing on a rock, looking out over the landscape, the historian can see over great distances with an air of authority; something audacious awaits. Yet, faced with such a huge vista, the historian is also remote and small. The past is tremendous, and cares little about one small wanderer who, descending from the heights, may soon become lost in nooks and crannies.

Staying on this paradox of particular and general, low and high ground, Gaddis quotes Machiavelli in The Prince:

For just as those who sketch landscapes place themselves down in the plain to consider the nature of mountains and high places and to consider the nature of low places place themselves high atop mountains, similarly to know well the nature of peoples one needs to be [a] prince, and to know well the nature of princes one needs to be of the people. - Machiavelli, The Prince, dedication to Lorenzo Medici

Sometimes a shift in perspective is needed to see something clearly. As Gaddis says, this paradox requires “an ability to shift back and forth between humility and mastery” (pg. 7). Part of what makes a mountain is its relationship to a valley, and vice versa, and part of what makes a prince is his relationship with his people. So too with history, and our relationship between past and present. “The best you can do, whether with a prince or a landscape or the past, is to represent reality: to smooth over the details, to look for larger patterns, to consider how you can use what you see for your own purposes” (pg. 7). The key word here is represent, which Gaddis elsewhere defines as “rearrangement of reality to suit our purposes” (pg. 20). Artfully selecting and arranging bits and pieces of reality for analysis lets us uncover meaning and significance. “For surely understanding implies comparison: to comprehend something is to see it in relation to other entities of the same class” (pg. 25). As the old wag goes, it’s difficult to understand the place you’re from until you’ve traveled somewhere else.

This might seem to clash with R.G. Collingwood’s assertion that we must understand the thoughts of those in the past as they themselves thought them; aren’t we distorting the historical record by comparing across times and places? As with any form of surgery, there is indeed a danger here. But Collingwood’s third proposition anticipates this problem - “Historical knowledge is the re-enactment of a past thought in-capsulated in a context of present thoughts which, by contradicting it, confine it to a plane different from theirs.” The very act of being in the present and rethinking past thoughts puts those thoughts on a different plane of reality. We are not actually traveling back into the past, but creating a representation of it, much like any map represents only a distilled portion of its chosen landscape.

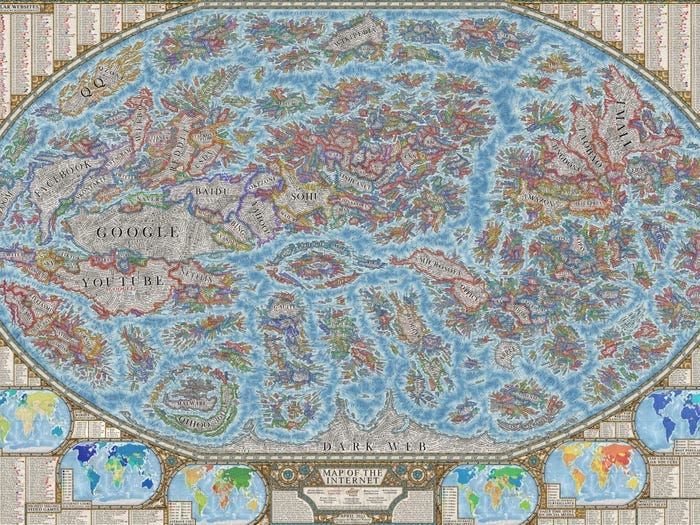

The virtue of maps lies precisely in their omitting of some details, so that others can be clarified. Gaddis recounts a fictional story from Jorge Louis Borges in which a cartography guild reached such perfection that they created a one-to-one map as big as their country itself. The map, being useless, was discarded in the desert (Gaddis, Pg. 32). Even a gigantic relief full of topographical details must smooth and average out bumps and deviations, and the smaller the map, the more it will compress. This abstraction applies to content as well as scale. A topographical map is appropriate for an army’s route of march, but Google maps needs to be able to show you the nearest Starbucks and account for traffic, and a map of all the major websites on the internet and their links to one another doesn’t even represent physical geographic space.

Maps are strangely relative in that we rate their quality by their intended purpose. A “good” pocket map will omit vastly more detail than a giant wall map, and a map of the New York Subway system won’t even bother to give you measurements in miles and feet. Maps are created and judged by the content and scale they intend to represent, in an exact parallel of R.G. Collingwood’s stubborn insistence on interpreting a thought only after its intended purpose has been firmly fixed and understood. The use and meaning of historical evidence is relative in that it can be applied and measured in almost any way the historian can dream up. An ancient shipwreck containing amphorae full of olive oil may seem a dull discovery, until you realize that the oil residue and minerals in the pottery can tell you where exactly the jars and oil came from, and thus something important about Roman commerce. And a Sumerian clay tablet inscribing a list of grain transactions can tell you a great deal about agriculture and social status if you know the right questions to ask of it.

Suddenly, small and seemingly isolated pieces of evidence, bereft of much meaning on their own, can form a broad landscape when viewed at scale, or in comparison. We can draw useful conclusions from large piles of evidence, even when we are uncertain about the value of individual pieces. Like a pixel on a screen, we may only derive limited information from the life of an individual medieval peasant. But with a large enough sample size, the pixels become a discernible image; a new map of the past, which can be used to chart a course, however hesitantly, into the future.

NB: This topic of historical interpretation has gone deeper than I intended, and I find I’m still only scratching the surface. I don’t plan for the average post to be quite so philosophical, but I think it’s useful to lay out my background and approach to historical thinking. Eventually, this newsletter will become much more content-focused. Next up - Some common historical fallacies. There may be a special pop culture-themed addendum piece out this weekend if I can finish it.