“All History is the History of Thought:” R.G. Collingwood and Reenacting the Past

Part three on the nature of history and why we should study it

As we saw last time, the past creates the present, and becoming a free individual requires knowledge of those past influences and their reverberations. But understanding those causal links is more difficult than it may seem.

The past, by definition, cannot be experienced; it can only be remembered or recollected. It is impossible to re-experience the same historical phenomena as someone else did in the past (or even to re-experience your own lunch from yesterday). How then do we “know” a memory, or a past action?

R.G. Collingwood was an early-mid 20th century British philosopher and historian who puzzled over this question for much of his career. From his experience with archeology, he decided that it was necessary to approach historical knowledge as the history of thought; for only by grasping the intended purpose of a thing could that thing be properly understood. Until that purpose and intention is known, the artifact or text in question is essentially meaningless.

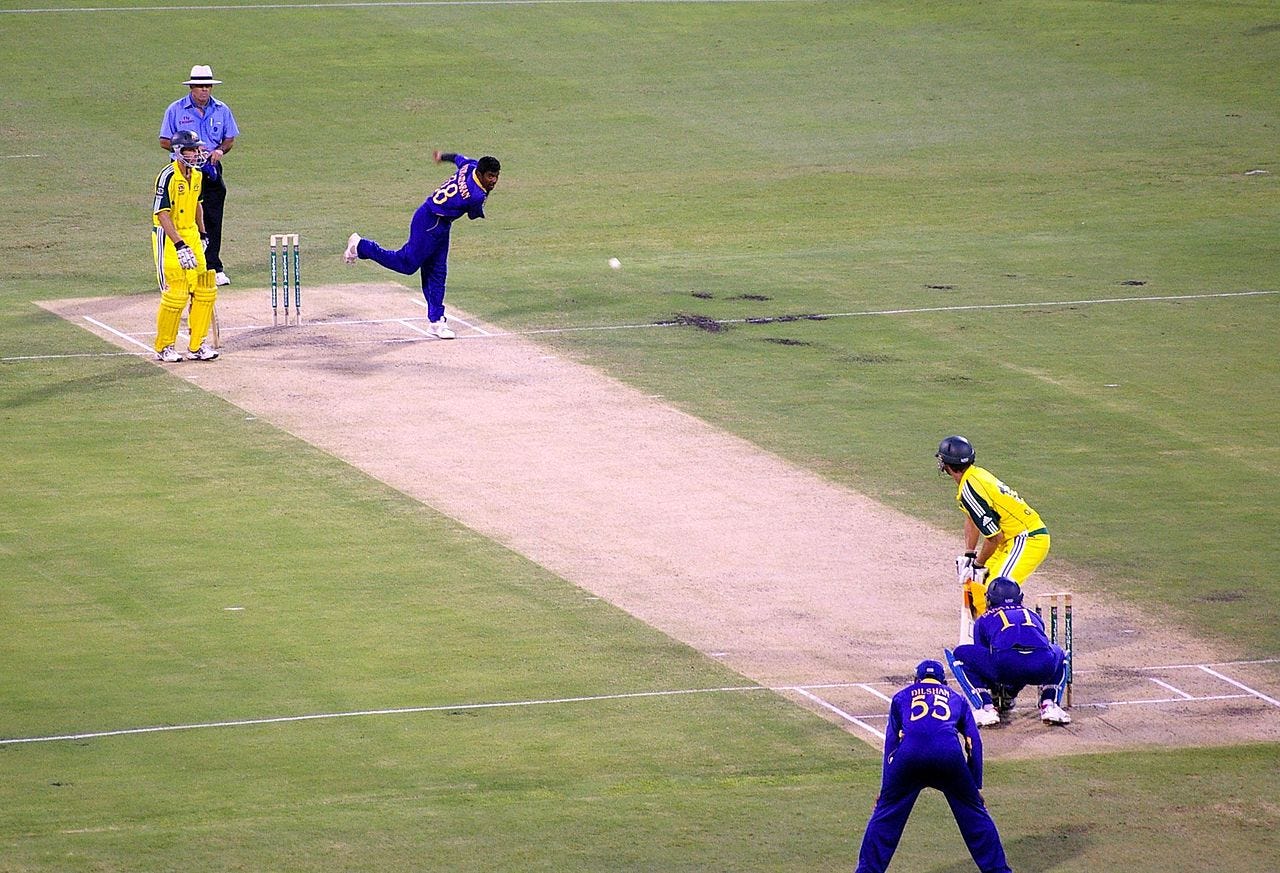

This may seem like a strong claim, but try playing a complicated board game where the rules haven’t been explained, or watching a game of cricket as an American. At first, actions and consequences seem almost random. Gradually, however, as you grasp the causal links between actions and their outcomes, you begin to understand the intention (thought) at work. Those who have mastered a craft often know their subject so well that they can predict likely moves and their outcomes, like football commentator Tony Romo predicting upcoming plays and their results in real-time.

Historical knowledge functions similarly. An unidentified length of bent iron dug out of an ancient house could either be a bad sword or a perfectly adequate poker for the fire, and only after discovering the purpose behind its creation will its nature make sense to the historian. Likewise, the surface-level meaning of a historical text (say, a letter urging someone to assassinate a close confidante of the king) may be clearly legible, but the “true” meaning of the letter could require much deeper investigation (to determine, for example, if the author of the letter was plotting to betray the king, or acting on the king’s behalf). Before the Rosetta Stone was discovered, Egyptologists could only make limited inferences about the meaning of individual hieroglyphics. This process is also cumulative; as one builds up a wider body of historical context and sees how it fits together, further discovery and interpretation becomes easier, as with an archeologist who can determine the date and location of making from even a small fragment of pottery.

Understanding of the “deep structure” of a thing makes it more intelligible, and therefore predictable. In Why Kids Don’t Like School (p. 134), cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham relates an experiment where chess experts and novices were both asked to place chess pieces on a board from memory, recreating a game in progress. The novices tried to “chunk” the pieces together based on physical proximity on the board, while the experts used the pieces' tactical relationships to each other to remember their locations.

For Collingwood, this process of understanding historical thought means being able to literally “rethink” it, and that recreation needs to be as close as possible to the original thinker’s intentions as we can. Collingwood uses the example of getting inside the mind of Lord Nelson on the deck of the Victory when deciding not to remove his medals and coat, even though they made him a conspicuous target for the French sharpshooters who cut him down. The historian has to understand, as closely as possible, the motivations which caused Nelson to refuse to remove his coat (“in honour I won them, in honour I will die with them”). If the wrong motives are ascribed, then Nelson’s action remains unknown:

“Unless I were capable–perhaps only transiently–of thinking that for myself, Nelson’s words would remain meaningless to me; I could only weave a net of verbiage round them like a psychologist, and talk about masochism and guilt-sense, or introversion and extraversion, or some such foolery.” - (R.G. Collingwood, Autobiography, Kindle Location 1324).

Collingwood’s emphasis on recreating historical thoughts doesn’t mean that those thoughts can’t ultimately be judged or even condemned, but that they have to be rightly understood before any real opinion can be made of them. If a Viking raider killed a monk standing over the tomb of St. Cuthbert, we ought to both recognize the universal morality of murder, and the particular set of cultural conventions and norms that helped swing the axe.

The genesis of Collingwood's proposition partly came from observing philosophical arguments at Oxford, and noting that even good scholars frequently spent great time and effort intellectually critiquing merely what they imagined their opponents to be saying, and not their actual propositions:

“I therefore taught my pupils, more by example than by precept, that they must never accept any criticism of anybody’s philosophy which they might hear or read without satisfying themselves by first-hand study that this was the philosophy he actually expounded; that they must always defer any criticism of their own until they were absolutely sure they understood the text they were criticizing…when my pupils came to me armed with grotesquely irrelevant refutations of (say) Kant’s ethical theory, and told me they came out of So-and-so’s lectures, it was all one to me whether the irrelevance came from their misrepresenting So-and-so, or from So-and-so’s misrepresenting Kant: my move was to reach for a book with the words, ‘Let us see whether that is what Kant really said.’” - (Autobiography, Location 347)

The empathy required to get inside the mind of another person, in a strange time and place, is an ability anyone can and ought to cultivate, and it can also help us view others as real people with real thoughts and actions, and not just as abstracted avatars of ideas or movements or cardboard cutouts for us to project our own theories onto. The historian has to be a good listener. (As an aside, arguing against positions only held by imaginary opponents probably also describes many modern political “debates” where partisans argue past each other and angrily skewer the positions that they imagine their opponents hold.)

Sometimes, the past is overtly strange enough that we realize we don’t understand it (for starters, we may literally have to translate it into our own language). Other times, however, it may seem superficially similar, and cause us to miss crucial hidden differences. The word “citizen” as used by Cicero is not quite the same as that used by modern democratic Americans, and applying 21st century assumptions about religion may obscure more than it reveals about early Christianity. Once again, the differences are sometimes more important than the similarities. A great many popular misunderstandings about historical time periods probably owe something to this assumption of things being more similar than they really are.

Other times, however, the strangeness of the past may cause us to look down on it and deride it, or write it off as worthless. The law codes of Hammurabi or the Salian Franks can seem utterly bizarre at first glance, and require a great deal of cultural and social context to make heads or tails of. Lacking this context, it’s all too easy to conclude that people in the past were foolish, and therefore not worth paying attention to. If we’re honest with ourselves, a great many things we write off as “uninteresting” may stem more from ignorance than genuine dissatisfaction (Though I confess that I often struggle with Tyler’s Cowen’s exhortations to apply this to modern art). Bored history students and children fidgeting while the adults drone on about “grown up stuff” have much in common.

That bored disposition, however, can instantly change to passionate interest if a key piece of information clicks into place, unlocking an entire conversation or topic. If we assume for a moment that people in the past were not always fools, but often did things for reasons that made sense to them, then we both respect them as fellow rational beings, and open ourselves up to the possibility of genuine discovery and learning (it’s difficult to learn from a subject of derision or dismissal). Past actors likely understood their situation better than we do, and it’s a good exercise to ask ourselves if it’s really all that likely that we understand a situation so much better than those who actually experienced it.

So historical knowledge requires understanding a thought as the original thinker (or as close to it as we can come). While this may seem harder to do for ancient subjects, and easier for more recent historical figures, even relatively recent time periods can feel remarkably foreign to us. The popular 80’s nostalgia in the show Stranger Things is a reminder of something that once felt very familiar, but no longer exists, and that jarring realization can reveal something to us about how much our own time period has changed.

There’s a final wrinkle to pull out from Collingwood’s description of historical thought. For even a recreation of a historical thought is still a recreation done by a historian who does not come from that time and place in question. As Collingwood put it,

“Trafalgar happened ninety years ago: I am a little boy in jersey: this is my father’s study carpet, not the Atlantic, and that the study fender, not the coast of Spain. So I reached my third proposition: ‘Historical knowledge is the re-enactment of a past thought in-capsulated in a context of present thoughts which, by contradicting it, confine it to a plane different from theirs.’” - (Autobiography, Location 1326)

The very act of re-enacting a thought is to put that thought on a different plane of existence from the original context, which is how we can apply that knowledge to present questions. We are able to “borrow” from the past and use it in the present. Throughout his autobiography, Collingwood describes this as something practiced by a historian, but he is also clear in saying that all philosophy is done in answer to some question which is ultimately historical (why did this come about, or why did someone think this?). Historical inquiry is something everyone does.

The results are spectacular, and line up well with the classical notion of education as truly liberal (as in, liberating):

“In knowing that somebody else thought it, he [the historian] knows that he himself is able to think it. And finding out what he is able to do is finding out what kind of a man he is. If he is able to understand, by rethinking them, the thoughts of a great many different kinds of people, it follows that he must be a great many kinds of man. He must be, in fact, a microcosm of all the history that he can know. Thus his own self-knowledge is at the same time his knowledge of the world of human affairs.” (Autobiography, Location 1337)

In withholding one’s own preconceptions and entering into the thoughts of others, we can take on the thoughts of almost anyone we care to learn about, and make their knowledge our own knowledge. Next week, we’ll consider how we can take that historical knowledge, and apply it onto the past more generally, as we go from individual human thoughts, to larger patterns. Up next: mapping the past.