Continuing our series in the early Roman Empire. Previous entries on Augustus, Caligula, and Claudius. These are adapted and revised narrative handouts I’ve written for students. Most primary source quotes and anecdotes from this reading are from Seutonius and Tacitus. This version has a bit more of the grown-up content added back in.

The death of Claudius, and accession of Nero -

Claudius proved to be a surprisingly good emperor in most respects, but one area of life that he never really figured out was women. He was married four times, never happily. His final wife, Agrippina the Younger, was a very forceful woman who managed (bullied?) to have her son Nero, from her first husband, made Claudius’ heir and successor. Claudius finally died in 54 AD. Many ancient sources suggest he was poisoned by Agrippina, as she had in fact poisoned her second husband, but this isn’t confirmed (her Wikipedia page has an entire sub-section listing her alleged murder victims).

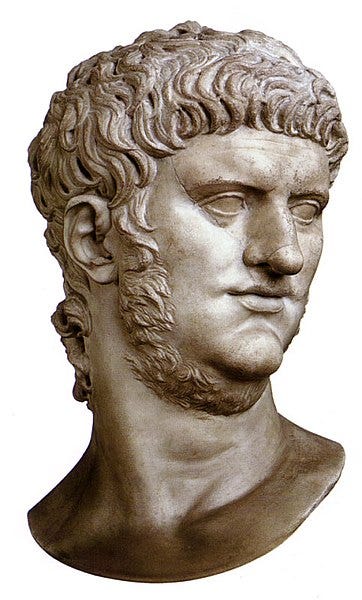

Nero (54-68 A.D.) is one of the most memorable of the Roman Emperors, but “memorable” doesn’t really do him justice. Nero is synonymous with tyranny, megalomania and decadence on a truly enormous scale, but it’s a strange sort of spectacle. We hesitate to say this, but it took a special kind of talent to be Nero.

Like Caligula, Nero’s early reign didn’t necessarily foreshadow how his rule would end. Nero was young when he took the throne, only 17, and still under the influence of his mother and his tutor, the famous stoic philosopher Seneca. With older figures helping advise and restrain the young princeps, things went fairly well. Trade and prosperity increased, and Roman armies won several important victories over the Parthian Empire in the far East. In 61 AD, the Romans put down a revolt in Britain, led by the famous Briton queen Boudica. This revolt actually happened after Nero started to spiral out of control, but it shows that the Roman administration and government (to say nothing of the military) were usually strong enough in the provinces by this point to run things even when the Emperor had “lost his touch.”

Nero started to change as he got older. He chafed under the influence of his mother and Seneca, and started to associate with other young noblemen who constantly flattered him. Under mounting pressure from court enemies, Seneca finally resigned his position and retired to the countryside to focus on his studies. Years later, Seneca was implicated (probably unfairly) in the Pisonian Conspiracy to kill Nero, and the Emperor ordered the philosopher to commit suicide. Seneca obeyed the order of his former student, and slit his own wrists while in the bath.

Nero’s mother, Agrippina, was tougher to get rid of. Tacitus and Seutonius suggested that Nero either had relations with his mother, or had at least wanted them. These rumors were later magnified when Nero took a mistress who supposedly looked a little too much like Agrippina, and the marriage of Nero’s eventual second wife, Poppaea Sabina, was postponed for a long time by Agrippina’s opposition (Tacitus has Poppaea basically call Nero a “momma’s boy”). As Nero finally distanced himself from his mother, Agrippina retaliated by backing Nero’s step-brother Britanniucs in a possible bid for the throne. Nero eventually poisoned Britannicus, and decided that his mother would have to go.

Reading the various accounts of ancient historians such as Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio gives a ridiculous picture of a black comedy of errors as Nero tried to kill his own mother. Some of the attempts are worthy of cartoon villains. Putting all the accounts together, we are told that Nero first tried to have his mother poisoned multiple times, but that on each occasion she drank the correct antidote. Nero then installed a mechanical ceiling in her bedroom that would collapse on top of her, and when that failed, he built a self-sinking boat that would drown her. But Agrippina swam to shore. Finally, at a loss, Nero simply went with the most direct method and sent assassins to kill her. According to Cassius Dio, when the killers approached her, Agrippina pointed towards her womb and said “strike here,” implying that it was her womb who bore Nero. If it was any consolation to her, Tacitus claims that Agrippina had been told by an astrologer years earlier, that her son would become Emperor, and would also kill her. Agrippina said “let him kill me, as long as he becomes emperor.”

With a mother like that, perhaps it’s no wonder Nero became...Nero. Nero’s second marriage, to Poppaea Sabina, didn’t end well either. Nero reportedly kicked her to death while she was pregnant, after she chided him for coming home late from the races. He did feel very bad about this, and gave her an emotional public funeral, in which Pliny the Elder claimed that he burned a year’s worth of Arabian perfume production in a single day. Some time later, Nero castrated a young male slave named Sporus, performed a marriage rite with him, and dressed him up to look suspiciously similar to his dead wife.

Free of his mother and tutor, Nero gave full vent to his passions. According to Suetonius, Nero became obsessed with gladiatorial games (even forcing Senators to participate, though not to the death), lavish parties, repeated romantic affairs (including another marriage ceremony with a male slave, with Nero playing the bride this time), and a deep obsession with Greek music and theater. He had himself trained by the best musicians and actors, and went on a grand tour of Greece, in which he competed in all the great games and contests, incredibly winning all of them (including the chariot race where he fell out halfway around the course). During Nero’s concerts, no one was allowed to leave for any reason, “no matter how urgent” (a woman went into labor and gave birth during one, while other audience members feigned death so they could be carried away). During a performance in Naples, he refused to stop singing even during an earthquake (likely near Mt. Vesuvius). Nero deliberately spent enormous sums of money at every occasion, awarding fortunes to musicians and artists and giving them mansions to live in. He never wore the same clothes twice, and played dice at four-hundred thousand sesterces per point. The extreme megalomania, utter lack of self-control, and terrified obedience of his servants who mutely agreed to every ridiculous demand he made have become a byword for decadent tyranny. It’s easy to see how the legend of Nero “playing the fiddle while Rome burned” sprang up.

- The Great Fire, Christians, and the Domus Aurea

In 64 AD, a fire broke out in Rome. Despite Augustus’ boast of Rome being a city of marble, most of the city was still very much wooden; and thousands of cramped apartment buildings relying on open flames for heat and light, and no real fire brigade were a recipe for disaster. Large fires in Rome weren’t that uncommon, but this one was particularly disastrous. According to Tacitus, over a third of the entire city was burnt to a crisp. The folktale that Nero started the fire and then performed a lyre-tune about the sack of Troy is perfect; but it’s probably not true, since even Tacitus says that Nero was out of the city at the time, and that Nero hurried back to help with relief efforts. But the story of Nero-turned arsonist refuses to go away, in no small part because of what he did next.

With Rome burned down and tens of thousands dead, the Romans needed a scapegoat to blame the whole thing on. And a small, secretive, and mysterious new religious sect was just what Nero needed for a sacrificial victim. According to Christian tradition, the Apostles Paul and Peter both died in the persecutions, while other Christians were dipped in tar and set on fire as human torches. The pyres were lined up every few yards in Nero’s garden, so they could provide light for a dinner party. We’ll meet these Christians again, and examine what the Romans thought of them more closely.

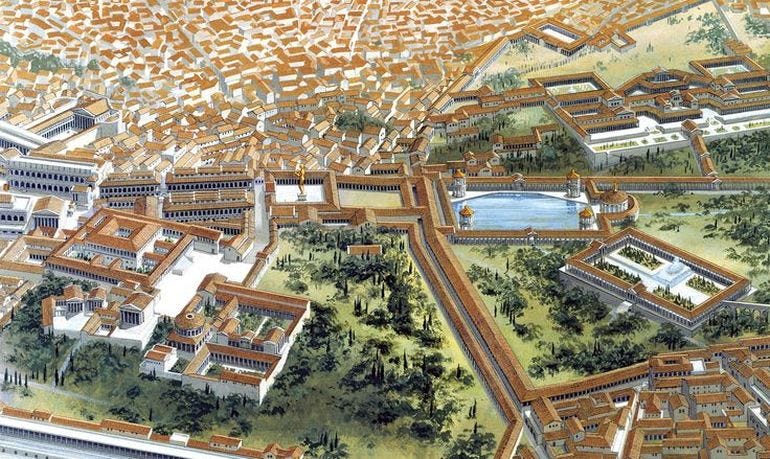

With a huge swath of the city flattened by fire, Nero had to decide how to rebuild. A chance to remake the center of a famous city from scratch doesn’t come along very often, so Nero decided to go for broke (literally. He bankrupted the treasury). Rather than public buildings, or improved housing for the poor, or even temples, Nero felt he needed a proper home to live in. Nero laid out a huge plot (possibly as much as 300 acres) in the very center of the city, in between the Palatine and Esquiline hills, and began to build his Domus Aurea (Golden House).

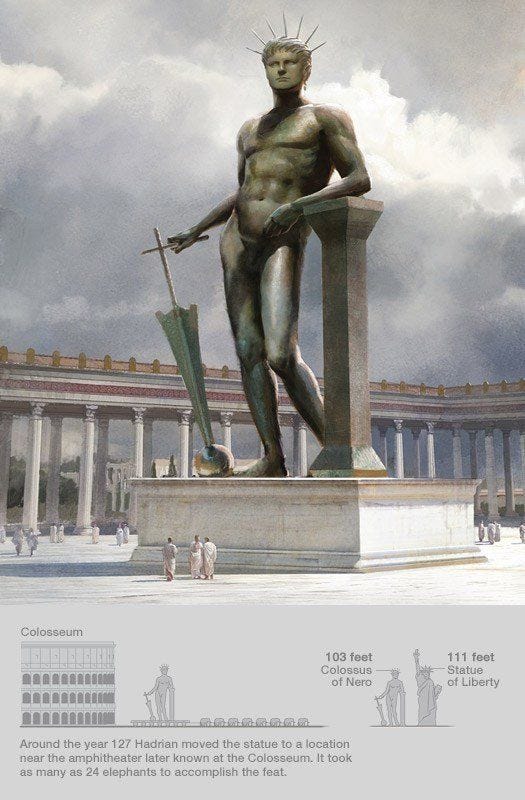

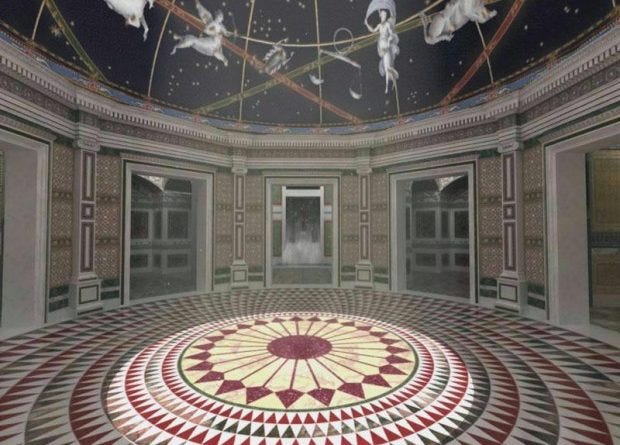

This massive palace featured a triple-colonnade over a mile long, a one-hundred twenty foot colossal statue of Nero depicted as the sun-god Sol, a multi-acre pond “like a sea” in the main courtyard surrounded by buildings to look like a city, and the whole thing was partially-enclosed by acres of parkland with trees and wild animals, tilled fields and vineyards, so Nero could feel as if he was still in the countryside. The “house” itself was basically history’s largest party-mansion, with over three-hundred rooms covered in gold and delicate mosaics (many on the walls instead of the floor, which was actually a key innovation in art-history). The piece de resistance was the famous octagonal room, with a rotating ceiling decorated with star constellations, and an open hole so rose petals could be dropped on the guests by the bucket, and walls containing pipes from which perfume could be pumped in. It’s quite possible that no one actually suffocated under the weight of rose petals, as that story cropped up later about Elegabalus as well. Despite the massive size of the palace, not a single bedroom has ever been found in it. Hundreds of years later, Roman hosts still gave out invitations to parties with Nero’s image on them. When the Emperor himself finally settled into his finished palace, he only said that he was finally able to live “like a human being.”

- Death of an artist

It was all too much. Nero had been quite willing to kill anyone who thought badly of him, but the endless carousing, debauchery, narcissistic opulence, and ridiculous extravagance finally caught up with him in 68 AD. While more than a few had thought about killing Nero (Tacitus’ description of the failed conspiracy of Piso and Nero’s retaliation is grim reading), what finally did it was the lack of money. With no coin to pay the normal military bonuses and the provinces suffering from heavy taxation, the increasingly disgruntled legions and their commanders finally revolted. A four-way civil war started, with multiple governors and military commanders all claiming the throne and vying to be the first to get to Rome and finish off Nero. Nero found himself abandoned in Rome with no public support (even the palace guards had vanished), and he finally fled towards a villa in the countryside. He finally resolved to take his own life, but didn’t have the courage to fall on his sword himself, and had to order a servant to run him through.

Before his death, all Nero could think was “ah, what an artist dies in me.”

That’s all for today. If time permits, I hope to have an extra post up this week on the historiography of Nero and attempts to “revise” him. Also, Plato’s account of the Tyrannical Soul from The Republic.