Continuation of a narrative series on the Roman Empire that began with Augustus. Earlier posts in the series have covered Augustus, the Teutoberg Wald, and Tiberius and Caligula. Next week’s post will be another meditation on the nature of history.

Caligula’s instability and megalomania finally led to his assassination in 41 AD by the Praetorian guard. Dating back to the earliest days of the Republic, it had been illegal for Roman soldiers to march under arms and in uniform inside the city limits of Rome (except for Triumphal processions), so the Praetorian guard enjoyed a singularly powerful position inside the city; they were the only men with swords near the center of power. But, as with many imperial bodyguards in history, the Praetorians eventually realized that being the only men with swords around the emperor cut both ways. Caligula would not be the only Roman emperor brought down by his own guard.

Claudius (reigned 41-54 AD) seemed a very unlikely candidate for emperor, and the story of his cowering behind a curtain and the soldiers spontaneously acclaiming him makes for great drama. But viewed more cynically, It’s highly possible that Claudius was either in on the coup attempt (he certainly didn’t like his family), or that the soldiers planned from the start to proclaim him emperor. Many Senators might have hoped to abolish the imperial office, and perhaps restore the Republic, but the Praetorian guard would hardly have wanted to go along with a restoration that would have led to their own dissolution.

Claudius was not an outwardly inspiring figure. According to Suetonius,

“when he walked, his weak knees gave way under him and he had many disagreeable traits both in his lighter moments and when he was engaged in business; his laughter was unseemly and his anger still more disgusting, for he would foam at the mouth and trickle at the nose; he stammered besides and his head was very shaky at all times, but especially when he made the least exertion.”

His awkwardness made him a target of mockery and ridicule within his family, many of whom believed him to be simple and unfit for any business:

“Whenever he went to sleep after dinner, which was a habit of his, he was pelted with the stones of olives and dates, and sometimes he was awakened by the jesters with a whip or cane, in pretended sport. They used also to put slippers on his hands as he lay snoring, so that when he was suddenly aroused he might rub his face with them” (Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars).

Still, Claudius hadn’t survived in his chaotic and cutthroat family for so long by accident. Behind his disfigurement lay a very sharp mind, that undoubtedly had watched and waited, and perhaps deliberately played the image of a harmless fool. Whether he had a hand in planning Caligula’s death or not, he quickly acted to secure his position. It was Claudius who started the trend, which over time would increase to almost absurd proportions, of paying large donative “bonuses” to the praetorian guard upon the accession of a new emperor. According to Suetonius, each guardsman received 15,000 sesterce, with the officers almost certainly receiving higher payments. Given that the average soldier in the regular legions earned about 225 denarii a year (each denarius was worth four sesterce, so a soldier earned 900 sesterce), this equaled more than 15 years’ salary to a regular soldier (though the guard was better paid to begin with). The officers almost certainly received much more.

Claudius had a scholarly disposition, and earlier in his life had actually wanted to write his own history of the end of the Roman Republic, starting with the death of Julius Caesar (but, explains Seutonius, this topic was too sensitive, since members of Augustus’ family were still alive at the time). Claudius mostly worked hard, kept the peace, assuaged the Senate, and expanded the Empire. He built one of Rome’s most important aqueducts, and added to the port at Ostia on the coast, complete with a lighthouse evoking the famous Pharos lighthouse at Alexandria, along with other building projects in the empire.

In particular, Claudius was noted for spending a significant amount of time taking a personal hand in matters of justice; sitting in court and hearing legal pleas and adjudicating cases. The personal authority and prestige of emperors meant that they gradually became a final court of appeals, as claimants and lower officials brought cases forward for adjudication. In the long run, much of the consolidation and extension of imperial power over the empire grew through the eventual formalization of this ad hoc legal process.

Claudius oversaw one of the Empire’s few major foreign conquests undertaken after Augustus, as most emperors were usually content to consolidate their rule over existing territories and keep the peace along Rome’s borders. The island of Briton had been a tempting target for Roman commanders ever since Caesar’s expedition there a hundred years earlier. In 54 AD, Claudius sent several legions to Briton to subdue the natives and extend Rome’s rule. The native Britons (who painted themselves in blue woad, and used war chariots) fought hard, but in the end Claudius traveled to the island himself to celebrate another conquest for the Empire, although he conveniently arrived after his generals had finished all the real fighting.

Roman Briton has an outsized influence in the Anglo-American imagination of the Roman Empire, thanks to popular stories about Queen Boudica’s rebellion, Hadrian’s Wall, and lost legions losing their imperial standards in battle. In reality, Briton was something of a backwater province during the early Principate, though it would become fairly affluent during the later empire. The famous “make a desert and call it peace quote” comes from a speech written by Tacitus about a British chieftain who launched a rebellion against Roman rule several decades after the initial conquest, and is not necessarily Tacitus’ direct opinion of the conquest.

- Romanization

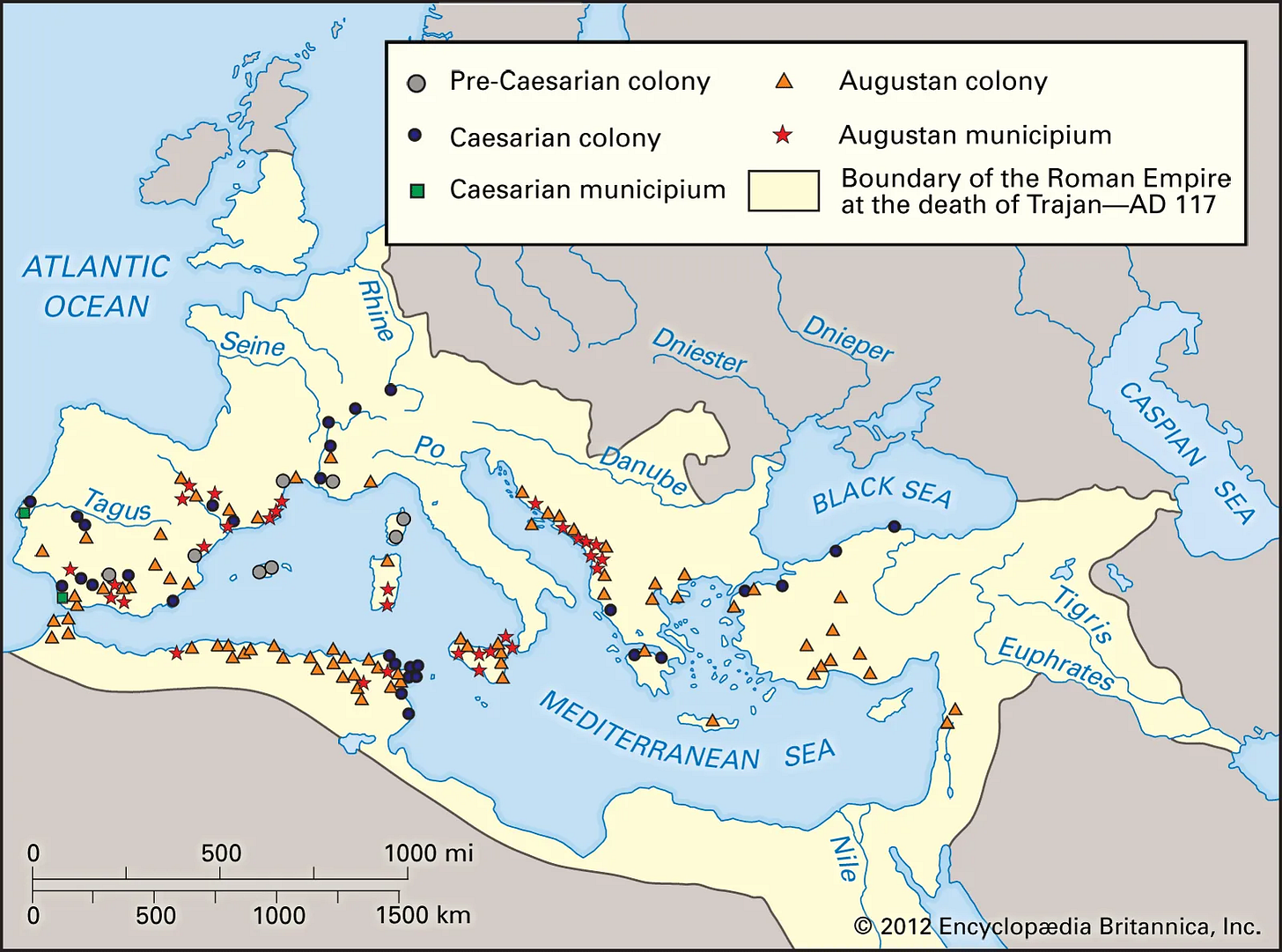

Claudius’ reign is a good point to pause and take stock of some changes in the Roman Empire. Originally, the expanding Republic had incorporated conquered peoples into a vast and extensive alliance network, under Roman headship. Conquered nations usually paid some form of tribute, had to contribute soldiers (known as auxillia) to serve in Rome’s wars, and follow Roman edicts, but were otherwise largely left to their own devices in terms of internal administration. Conquered provinces were administered by either the Senate or Imperial family, but local government was still fairly free of direct Roman rule. While there was a very large “Roman Empire,” only a very small percentage of the people living inside it were actual Roman citizens enjoying the privileges and protections of Roman law.

Over time, this loose system began to change and harden, as Roman influences began to seep into almost all features of life throughout the empire. The Roman government gradually took on more and more direct rule of provinces and territories. In fact, in some places, this happened with active participation of the locals. Gradually, new cities and townships grew up throughout the empire built along explicitly Roman lines, and with constitutions modeled on Roman law. These cities (municipia) usually ended up getting Roman citizenship themselves. Often, they had a founding core of retired soldiers given land-grants as part of their service. These colonies became a rapid growth-agent for romanization, as the far-flung provinces of the Roman Empire began to look more and more “Roman” in almost every sense of the word.

In 40 BC, the newly conquered territories in Gaul would have been utterly Celtic and foreign to Roman eyes, except for visiting Greek or Roman wine merchants and slavers. But by the reign of Claudius, it was possible for well-bred natives of Gaul to make their way into the Roman Senate. By the reign of the Five Good Emperors in the 2nd century AD, many inhabitants of Gaul were thoroughly Romanized. They wore togas, cut their hair like Romans, spoke Latin, and the wealthiest learned Greek and rhetoric. The historian Adrian Goldsworthy has noted that most rebellions and calls for independence on the part of locals only happened in the first few decades of Roman rule. In fact, when the Roman empire collapsed, most locals viewed the collapse as their own loss, and not a chance for renewed independence. While there were plenty of rebellions in the later empire, these always featured ambitious generals who desired to become emperor themselves.

We should emphasize again that this conquest of Roman culture was not carried out at the point of the sword. It may not have been exactly voluntarily on the part of the locals, but time and again local inhabitants realized that they had a lot to gain from willingly joining the Roman system. Probably more than anything else, Roman civilization offered the protections of Roman law, trade, and transportation, Greek culture, and access into the Roman elite. Rome’s famous road network that crisscrossed the empire enabled the rapid spread and exchange of goods, services, ideas, and eventually, culture. Roman law offered the ability to easily conduct business with anyone else in the empire, and it offered much more confidence to individuals that any legal disputes they had would be settled fairly and (relatively) impartially. It’s amusing to find the Apostle Paul, who wrote so powerfully about shedding all things extraneous to faith, very quick to assert his Roman citizenship as a legal protection in the face of persecution. Even when condemned, Roman citizens had to be executed “humanely,” so while the Apostle Peter was crucified (upside down according to tradition), Paul was beheaded.

The benefits of this system are hard to overstate. For the first time in Western history, the known world was interconnected, stable, and largely trustworthy. The economic benefits to the empire were significant, and the standard of living and wealth in the empire increased through the middle of the second century. It’s easy to lose sight of this transformation of the ancient world against the backdrop of a drama-filled and highly entertaining imperial family in Rome. Speaking of family drama…next up is Nero.