The Early Roman Empire and the Principate - Augustus

Ch. 1 - How Octavius killed off the Republic by pretending to save it

- Death of the Republic

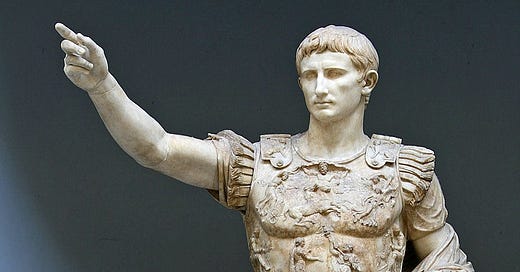

Gaius Octavius Caesar (reigning from 31BC to 14 AD, and known as Augustus after 27 BC) was an unlikely bet to kill off the Roman Republic and end the disastrous violence previous century. Finally ending with Antony and Cleopatra’s defeat at Actium in 31 BC, The Republican Civil Wars had been a decades-long series of struggles between strong political figures vying for power, chiefly through use of the military. Almost all of the big leaders in the late Republic - Marius, Sulla, Pompey, Julius Caesar, Mark Antony - had been generals first and foremost. Even the exception, Crassus, used his wealth to pay for an army so he could gain military prestige. The Romans had always valued military service as one of the highest occupations, and by the late Republic this was taken to the extreme. If you wanted to finagle your way into high political office, you made sure you had a few victories and conquests to your name if at all possible.

Gaius Octavius was a very serious student of philosophy and politics. Ironically, the relentless quest of the military generals to achieve power meant that they often weren’t well trained to actually use and keep power once they had it. Octavius was, and he avoided the pitfalls of his predecessors. Most importantly, Octavius avoided presenting himself as a king or absolute ruler of the Republic. He went to great lengths to portray all of his actions as preserving the Republic and the Senate, and publicly refusing absolute power. He praised the Senate, and a number of years made a great show of stepping down from the consulship. On the surface, the Republic was saved and restored.

It was superb theater. Behind the scenes, Octavius made sure that all the right people were in the right positions of power, and that they answered to him. He packed the Senate with political supporters who owed their position to his patronage, and made sure that the military either answered to him, or was run by non-entities. While he publicly refused power, he perfectly understood the value of reputation and prestige. He artfully arranged for the Senate to give him a number of honorific titles that elevated him as the chief man in Rome. He was declared “August” (meaning “revered,” and from which his name Caesar Augustus comes from), and Princeps, or “First Citizen.” As Princeps, Octavius (no, let’s call him Augustus now) was claiming to be a great man and the de facto savior of Rome, but still only a citizen, in theory just like everyone else. This meant that Caesar Augustus could sidestep terms like “king” and “tyrant,” that all good Romans hated. If anyone complained about him as a ruler, he could claim that he was “just a citizen,” and that the Senate and people ruled Rome once again. Granted, he had also been given Imperium (“right to command,” from which our word Emperor comes from), and many informed Romans could see that all the real power ran through Augustus (who maintained legal veto power over the Senate), but it was enough of a pretense that most Romans put up with it, as long as they were content and things got back to normal.

And in a sense, things did get back to normal. The other half of Augustus’ genius for ruling was that he was simply a good administrator. He knew that if peace was kept, law and order maintained, justice served, and the plebeians fed on bread and circuses, people would put up with one-man rule as long as it wasn’t rubbed in their faces. The historian Tacitus, writing much later and lamenting the fall of the Republic, pointedly said that “Augustus won over the soldiers with gifts, the populace with cheap corn, and all men with the sweets of repose, and so grew greater by degrees, while he concentrated in himself the functions of the Senate, the magistrates, and the laws.” After years of devastating civil wars that killed hundreds of thousands throughout the Empire (and most of Augustus’ potential rivals), people went along with the slow erosion of their political liberties because many of their immediate concerns were met, and because they could rationalize things as being much better than they had been during the tumultuous days of Pompey and Julius Caesar. To be fair, Rome had been in turmoil for so many decades, that no living person could remember a functioning Republic. Ultimately, Augustus bribed everyone with peace.

Tacitus had the benefit of hindsight and greater historical perspective; he could see that Augustus’ efforts had gradually entrenched one-man rule. Keeping true political liberty in any society is very hard to do. People might talk a lot about principles and virtue, but they will often enough trade their liberty away when faced with danger. Previous instability, failure of government, and outright violence (the civil wars of the Triumvirates) laid the groundwork for the tacit acceptance of an Emperor, so long as he could keep the people and the army happy. The remaining virtues of the Roman Republic slowly died away.

A good window into how Augustus operated and managed to kill off the old Republic, is the Res Gestae (“Deeds of Augustus”). Augustus inscribed a list of his achievements into bronze and had them displayed all across the Empire. The Res Gestae celebrates all of his achievements, from the defeat of his enemies (like Mark Antony), to his foreign conquests, to all the money spent on public works and infrastructure. It is very careful, however, to portray all of these achievements as being done on behalf of the Republic and not for his own aggrandizement. And any honors or titles taken by Augustus, are painstakingly portrayed as being given voluntarily by a grateful senate and people (of course, this was the same Senate that Augustus had packed with hand-picked supporters, and possessed full veto power over).

- The First Emperor

As princeps wielding imperium (right to command), Augustus ruled the Roman Empire from behind the scenes. In addition to re-establishing the rule of law and stabilizing the politics of the Empire, he set to work building infrastructure and public works, cracking down on corruption, and strengthening the army. He even cared about the social welfare of the public, and, worried about declining birth rates and morality, passed laws encouraging families to have more children and to discourage divorce. Augustus cared a great deal for promoting public religion, and rebuilt many temples that had fallen into disrepair. While the temple to Mars Ultor in his new Forum complex highlighted his military achievements, Augustus also built the ara pacis (altar of peace), and famously closed the doors of the Temple of Janus, which were always opened during times of war, for only the third time in Roman History

Augustus even exiled the poet Ovid for his scandalous writings and affairs (rumored to have included Augustus’ own daughter, but possibly just for Ovid’s scandalous Ars Amatoria, a shockingly Machiavellian handbook on seduction). Abroad, he expanded the Empire along the Danube, in Asia Minor, and in Egypt. Egypt was incorporated as a new province of the Empire, and became one its greatest sources of wealth and grain. Of course, these achievements were carefully orchestrated to give Augustus all the credit and glory, while still avoiding calling him a king or tyrant. It’s not an accident that Virgil wrote the Aeneid during the reign of Augustus. The Aeneid remains one of the greatest works of Western literature, but it was also a brilliant piece of public propaganda (with no insult intended). It gave the Romans a founding myth to celebrate on par with the works of Homer, while also subtly portraying the entire destiny of Roman history as leading up to the reign of Augustus. Recall Aeneas’ visit to the underworld.

With the violence of the civil wars gone, the economy rebounded. One of the most important keys to prosperity is the ability to carry out commerce without fear of violence or tyrannical confiscation from the government. If pirates infest the oceans, you won’t trade with people far away for fear of losing your ships. If warring armies are destroying cities and snapping up plunder without paying for it, merchants will go out of business. But, if there’s peace, and if there are established and reliable trade routes that enable long-distance travel, commerce can take off. Generally speaking, the Roman Empire enjoyed unparalleled prosperity because there was no threat of invasion or violence within the boundaries of the empire, because the roads were well-built and safe, and because the rule of law was enforced (you knew that you could transact business over great distances because the government was generally effective at enforcing contracts and catching criminals). People could be reasonably sure that their own property would be protected and wasn’t going to fall prey to marauding armies (either Roman or Barbarian), or even to the whims of a tyrannical government. If you add all these benefits up, you get a famous phrase known as the Pax Romana (“Roman Peace”). The Pax Romana described the general security, peace, and prosperity of the Roman Empire. It was such a positive term that people have subsequently used variations of the theme to describe other successful Empires in history (Pax Britannica for the British Empire in the 19th century, Pax Mongolica for the Mongols, and sometimes even the Pax Americana to describe the United States).

- Divus Augustus, and a Child-Birth in Judaea

Augustus Caesar ruled for a very long time, and finally died of old age in 14 A.D. He left behind him a much more stable and stronger Roman polity, but one with almost all hope of the liberties of the old Republic fading away. By the time of Augustus’ death, most younger Romans couldn’t remember the battle of Actium, and no one alive could remember a time before the destructive civil wars. The Pax Romana under one-man rule was in place, and people went along with it. As a final embellishment of his prestige and authority, the dead Caesar was proclaimed Divus Augustus (“Divine Augustus”) and was given his own temple as one of the gods, initiating the tradition of deifying Emperors upon their death.

Augustus’ reported last words were, “have I played the part well? Then applaud as I exit.” This was a telling note on how he had so carefully scripted his rule to keep up the fiction of Republicanism. Publicly however, it was put out that his last words were, “Behold, I found Rome a city of clay, and I leave her to you a city of marble.”

Caesar Augustus was one of the most important figures in the ancient world. Few other individuals could have so successfully stabilized Rome and laid a new foundation for the Empire after the disasters of the civil wars. The hegemony of the Roman Empire over the next four centuries would help solidify and expand the legacy of ancient Greece and Republican Rome all over Europe, and ensure that “Western Civilization” would actually become a tradition and civilizational ideal that outlasted the ancient world. We still benefit from Augustus’ pax romana.

The first two centuries of the Roman empire (27BC to 180 AD) are known today as The Principate period, because each emperor at least paid lip service to the fiction of “merely” being princeps. The Roman Senate continued to meet, consuls and magistrates were elected, and the best-remembered Emperors usually gave the courtesy of pretending to ask for the Senate’s advice and consent. It’s worth noting that most of the infamous emperors we still remember as tyrants (mostly for good reason) frequently clashed with and/or ran roughshod over the Senate. Aristocrats will sometimes tolerate having little real power, as long as you don’t go out of your way to remind them of it.

But Augustus wasn’t the only person in his day who would transcend history as one of the most important individuals ever. A little more than halfway through Augustus’ reign, a seemingly insignificant child was born in one of the most remote and unimportant backwater provinces of the Roman Empire. According to the Gospel of Luke, the birth happened in Bethlehem chiefly because of a census decree sent out by Augustus himself. Jesus of Nazareth would go on to be even more important to history than Augustus. We will look at the intertwining history of the Christian Church and the Roman Empire from time to time as we go forward.

Hello Mr. Rogers