Widening the Historical Lens

Translating history is more than just a matter of linguistics, and when done well it can sharpen our focus of more than just the past.

Continuing on the theme of pre-modern vs. modern historiography, ancient historians are sometimes criticized for overemphasizing politics and warfare, and ignoring what we might today call social history. Likewise, traditionalists and other advocates of pre-modern historiography sometimes criticize modern history for dethroning great men and heroes as models for emulation.

Tocqueville noticed this change of focus in Democracy in America, as part of his emphasis on the role of equality in Democratic societies. If, in democracies, men (and implicitly, women) are socially and politically more equal, then great leaders and heroes will be demoted in favor of broader inquiries into peoples and nations. Tocqueville easily discerned the rise of 19th century social historians who talked about the spirit of whole peoples and civilizations, as well as the mechanistic operation of historical systems. Contemporary historians today don’t talk about the “spirit of civilization” anymore, but they tend to focus even more heavily on covering a wider variety of groups and individuals.

Last time, I attempted to briefly steelman the writing of pre-modern history, and look at why ancient historians had understandable reasons for often focusing on politics, war, diplomacy, and the like. In addition to the difficulties of doing modern-style social history, the pre-modern world really was one where elite individuals played larger and more prominent roles. In a society where fewer individuals wielded a greater degree of agency and influence, focusing historical education on those individuals was understandable. I don’t think this was just a matter of snobbish elites, though undoubtedly some of them were.

Now, I’d like to look at what the tools and methods of modern-style social history can tell us about past societies, about how the modern world really does represent a major change from that of the ancient.

The shift in focus towards social history is often described as bringing attention to previously under-emphasized or overlooked parts of history; finally given attention to and acknowledging the unsung roles and contributions of peasants, women, minorities, slaves, etc. The understandable claim is that while ancient and pre-modern historians wrote about kings arranging diplomatic marriages and generals ordering brilliant flanking maneuvers in battles, large swaths of society toiled along unnoticed, playing important and meaningful roles in history that political and social elites mostly ignored.

As I talked about last time, I think one thing that’s going on here is that modern historians have many more tools and abilities to access and study those parts of history. Modern archeology, mass literacy, and ready documentation of contracts and legal actions all make studying different social classes easier. A wider world with access to more national cultures and histories also makes social history easier, and more interesting; the history of one social group becomes more meaningful when you can compare it across times and cultures, just as traveling abroad for the first time gives a person much more context for understanding their own home.

I don’t think I elaborated on this point (about having better tools and methods) very well in my previous post, so I’ll offer a couple of examples, including one that straddles the pre-modern/modern divide.

In Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation, historian Peter Marshall talks about clerical chastity in Late Medieval England on the eve of the Reformation. The notion of priests and monks failing to live up to their vows of celibacy is a well-worn trope running right back through the Middle Ages, and the early Protestants themselves were not the first to complain about priests and monks visiting brothels and maintaining common-law wives. Scandalous behavior naturally draws attention and the ire of moral idealists, so it’s not surprising to find our literary sources from around 1500, including devout Catholics such as Erasmus and Thomas More, expressing anguish about the moral standards of the clergy.

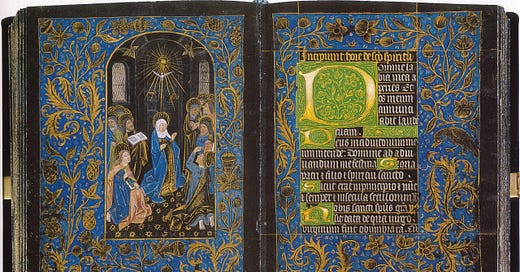

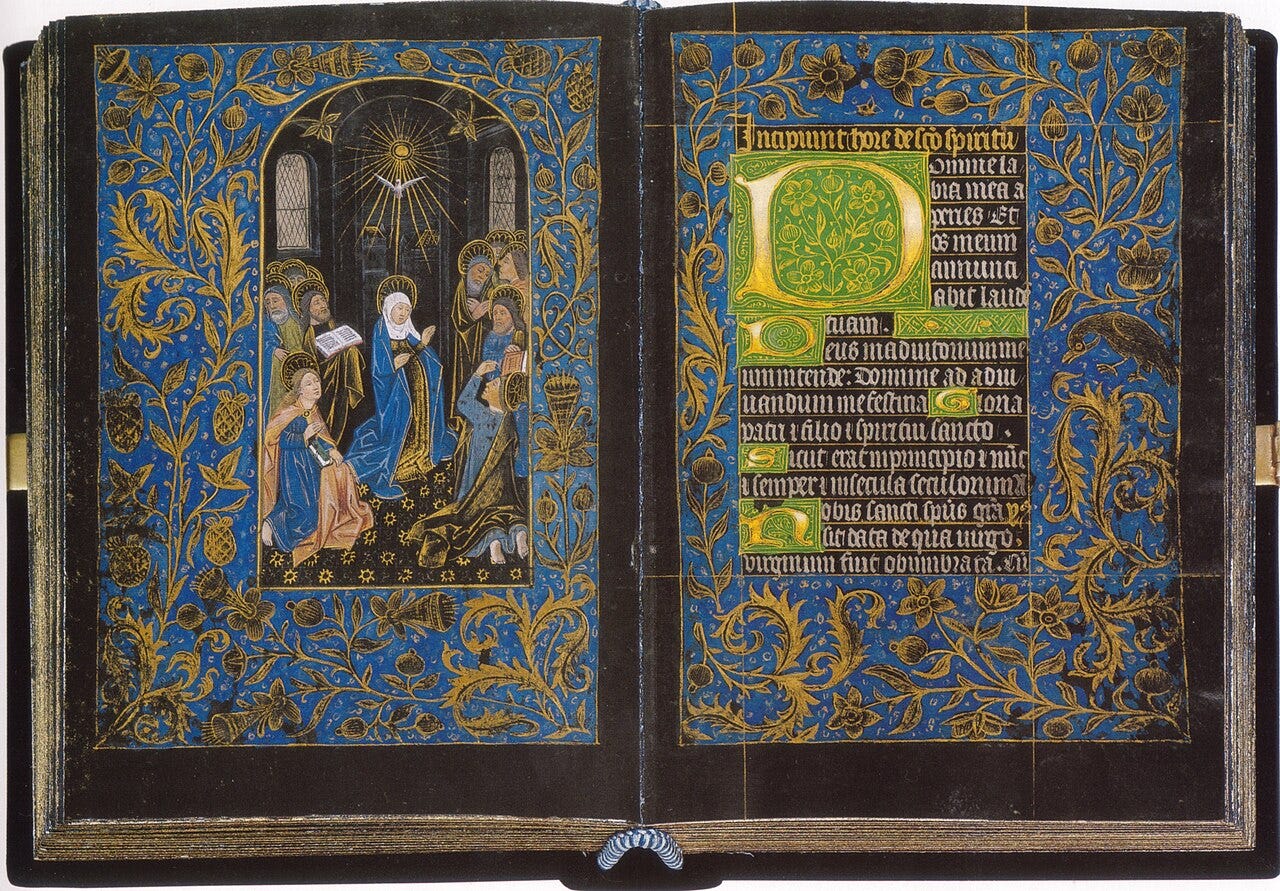

To double-check the popular sentiment, Peter Marshall surveyed a number of diocesan records to look for records of complaints brought by parishes to their local bishop; 5 complaints out of 478 Suffolk parishes, 9 out of 260 Kentish parishes, and 102 priests out of 1,006 in Lincoln. Marshall concludes, “these findings suggest that, on average, well over 90 per cent of clergy were routinely maintaining chaste lives.”1 This is probably better than what many reformers might have imagined. Marshall’s work is of a piece with much contemporary historiography on the Reformation, which has overturned older narratives about Late Medieval religion being cold and dry, with a disinterested laity far removed from a power-hungry and corrupt church-establishment. My general impression of contemporary scholarship (I make no claims to detailed knowledge here), suggests that late medieval religion was instead often enthusiastic and engaged, with eager crowds gathering to hear hours-long public sermons on high feast days, and a rising literate mercantile class wanting to make use of the newfangled printing press to purchase religious works and lay editions of the liturgy of the hours. In fact, it would make sense for this to be the social world in which Martin Luther would go viral.

Elsewhere, I recently found something similar in regards to the economy of the Late Roman Empire and its imperial bureaucracy. In Anthony Kaldellis’ huge new Byzantine history, The New Roman Empire, Kaldellis tells us that:

“Diocletian’s tax system was long believed to have crushed the peasantry with its exactions, but this bleak picture has been radically revised. There is now mounting archeological and textual evidence for peasant prosperity in the fourth and fifth centuries…far from crushing small farmers, the new tax system may have spurred their economic productivity while shifting some of their prior tax burden to wealthier landowners, leading the latter to construct the familiar complaint of an oppressive state.”2

This new picture of the late Roman economy isn’t as overly-reliant on literary sources from the senatorial class, and helps explain why the more economically-complex Eastern Roman Empire actually held up well during this period, meeting more of its fiscal and military challenges than did the Western Roman Empire.

In both examples, it’s easy to see how the older interpretation came about, and for very understandable reasons. It’s hard to imagine Renaissance humanists and reformers carefully surveying parish archives and trying to establish statistical base rates to estimate moral behavior, or Roman senators calculating per-capita productivity in shifting population centers. Also, even if the interest was there, the ease of modern travel, electronic communication, and digitization of information, makes such research vastly more feasible today.

So then, modern historiography can more easily shine a light on previously undervalued and overlooked parts of society. This is the usual interpretation you’ll often hear from modern historians, and it’s this framing that often gets pushed back on by traditionalists who counter with those important moments where great men and events continue to cast large shadows on the historical record.

However, I think this is only part of the reason for the importance of modern-style social history. Modern “democratic history” in the Tocquevillian sense doesn’t just reflect the fact that non-elite social groups are important and worthy of attention, but reflects the fact that non-elite social groups are actually now more important to begin with. To put it another way, historical writing has needed to widen its focus, not just because important groups were being overlooked, but because those groups actually matter more now than they did in the past. Proportionally, over the last few hundred years, the degree of agency and influence wielded by elites has shrunk, and that of everyone else has grown.

This isn’t a judgment about the moral worth or value of any individual or group, but a statement about their ability to impact history. We can applaud the faith of the Apostle Paul, who ascribed infinite moral worth to slaves and women, and still recognize that women and slaves in ancient Rome had less agency over their lives. Indeed, that lack of agency is what scandalizes modern sensibilities.

It’s perfectly fair to say that medieval peasants had meaningful lives, and fulfilling relationships in vibrant cultures, and that those lives are worthy of study. In fact, because our own day and age is so different, we need to be able to accurately re-imagine the lives of Sumerian brick-layers, Greek housewives, and manorial peasants, else we won’t be able to grasp the basic shape and texture of their societies in the first place. Rather than topics to include for the sake of not leaving anyone out, the lives of these groups might need to be our very starting point. But even so, we’re usually trying to understand those individuals as representatives of a group. The question, “what was it like to be a Chinese peasant?” is aimed at the average, and the most unique and distinctive stories would actually skew our understanding of the whole. We’re not keeping as much appreciation for the individual as we think.

While medieval and renaissance art could easily imagine the world of the Bible as visually identical to its own day, we moderns must confront the strangeness and sense of difference about the past in order to even begin to understand it. Accurately or not, a renaissance historian could take much of the past for granted, and assume life was similar in many ways. Beyond language, the past didn’t need as much translation. But for a modern audience today, we need to translate much more than just language in order to understand the past.

When reminding students about the biggest ways in which most of history was different from today, I end up with a list that includes (among other things) the ubiquitous prevalence of subsistence agriculture, the difficulty of transportation and communication over distance, low literacy and high mortality rates, and dense family and kinship networks. Outside of the extreme outlier cases such as steppe nomad environments, there are only two exceptions to this general pattern. Those two exceptions are life in cities, and the broad contours of the modern world starting around 1500, and accelerating after 1800.

Earlier I mentioned the value of traveling abroad as a way to better understand one’s home; and the same idea goes for understanding the modern and pre-modern world. Because the more you’re able to internalize the old saying about how “the past is a strange place, they do things differently there,” the more you’ll notice just how remarkable the modern world is. This is the world that Tocqueville was so fascinated to describe in Democracy in America, and the world that we mostly take for granted today. Widening the historical lens on the past, can also help sharpen the lens on ourselves.

Cities and the rise of the modern world is where I hope to focus next, though I hope to pull together some thoughts on military-history and present day conflicts as well. Unsure of the exact order of publishing at the moment. Sincere thanks to all who have subscribed and shared.

Peter Marshall, Heretics and Unbelievers, 2017 Yale University Press, pg 101.

Anthony Kaldellis, The New Roman Empire, 2023, Oxford University Press, pg 39.