Why You Will Not Be Drafted Into WW III

20th-century Total War and Mass Conscription No Longer Explain Modern Conflict

Several times over the years, I’ve been asked by students if I think one day they’ll be drafted into the military, in order to fight China in WWIII. This is usually idle speculation, an attempt to get the teacher off on a tangent, or a what-if question stemming from discussing the Thucydides trap and the Peloponnesian War.

They don’t know it, but what students are really asking is, “will there be another large 20th century-style Total War?”

I won’t make any predictions about whether the U.S. goes to war with China. I certainly hope we don’t. What I will say, however, is that I think a future war, even a global conflict, won’t really look like “World War Three” does in our imagination. And I think the odds that a student of mine gets drafted to fight in that conflict are low, because a 20th century-style draft and mass mobilization simply won’t be that useful.1

So the short answer to the question is, “no.” The longer answer reveals a great deal about modern history and the way the world has changed, which go far beyond the narrow interest of military history buffs arguing about weapons specifications. This change is partially caused by changes in warfare and technology, but just as much by deeper patterns in society, including state capacity, demographics, and the complexity of modern economies.

Consequently, 20th century Total Wars are probably not the best guide for thinking about the future, and I think we need to look further back in history for examples to draw on. Perhaps more 30 Years War, and less “World War III.”

20th Century Industrial Total War

When we think of large-scale conflicts, Americans automatically think of World War II and the Civil War. These are our iconic “good” wars, unlike more morally complex and less-clean cut conflicts such as Vietnam and the War on Terror, and which play to American strengths of technological prowess and industrial might. They are also classic examples of what historians call Total Wars.

During the 19th and 20th century, strong national governments mobilized entire populations and industrial productivity, throwing entire nations into conflict. This process began during the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, with the levee en masse, and rapidly progressed over the next hundred and fifty years. Most people know that World War I saw the use of terrifyingly destructive new weapons such as artillery and machine guns, but what really made World War I the “war to end all wars” was the industrial might that produced, equipped, and fed millions of men under arms indefinitely. Napoleon’s armies frequently still “lived off the land” (meaning, stole food from peasants), and fought on battlefields a few miles across. In contrast, World War I armies were supplied year-round by railways and steamships bringing goods from factories, and were so numerous that their trenches scarred the face of an entire continent.

Along with these feats of organization and industry, modern nation states secured extraordinary levels of commitment and buy-in from their populations, coupled with the ability to compel obedience and participation in the war effort when necessary. The literature across this period is full of stories of mass voluntary service, and spontaneous outbursts of patriotism and national fervor, including within the diaries and letters of individual soldiers. Governmental propaganda urged along these efforts, using newspapers, radio, and television as new forms of mass media, but these efforts merely encouraged and amplified existing levels of patriotism, fostered by national education systems and popular literature and history. Great Britain started World War One with a small, highly trained, professional army, but, alongside conscription, rapidly filled out Kitchener’s Battalions full of eager volunteers. Hundreds of thousands of dutiful young men joined units drawn from the same local towns and shires. Huge numbers of these young men died together at the Somme.

These wars were wars of scale and bureaucratic prowess, from the fantastically fine-tuned German railway tables at the start of World War I, to America building the largest office building in the world during World War II (the Pentagon). One of America’s secret weapons during the war was Harvard’s Business School, churning out graduates to staff the war planning effort. This organizational capacity leveraged industrial output and manufacturing on a dizzying scale. During World War II, the United States built 300,000 aircraft, almost 90,000 tanks, and by 1945 had over 6,000 naval vessels (including smaller craft).2

Strategically, Industrial Total Wars also sought total victory. The Civil War ended in Richmond, and the Franco-Prussian War in Paris. World War One ended not simply from defeat on the battlefield, but when Germany realized that national collapse was imminent. The governments of Russia, Austria, and Germany all fell or were overthrown by the war, followed soon after by the Ottomans. During the Second World War, the Allies famously demanded the unconditional surrender of the Axis Powers, which only transpired after Berlin had been turned into rubble, and Japan’s cities had been firebombed and atomically incinerated. Among pre-modern armies and warfare, few examples come close to this level of complete destruction and defeat.

The most famous theorist of modern war, Carl von Clausewitz, outlined a triangular relationship between a state, army, and people. Each directs, supports, or defends the others, and must function together, and destroying any side of the triangle will also lead to the defeat of the others. You can still see this relationship at work in pre-modern states, but with the lines muddled. In medieval feudalism, lords and vassals functioned as both government and army simultaneously, whereas tribal societies might have little or no distinction between each part, as in steppe nomad societies. 19th and 20th century nation states attempted to carry these distinctions to their rational (destructive) conclusion. Clearly-defined armies fought each other and sought the overthrow of governments, which represented civilian populations who paid taxes, worked in factories, and provided the manpower for those armies.3 This model was fantastically successful, and fantastically destructive. It’s still our default image for what war “should be.” Notice the frustration of counter-insurgency warfare against terrorists and irregular forces in Vietnam and the Middle East. Such enemies muddle Clausewitz’s triangle, by hiding amongst civilians and refusing to wear uniforms and fight in the open.

So in our popular imagination and understanding of war, we naturally and understandably draw a line of progression from the 19th century through to the 20th, and beyond. The Civil War was incredibly destructive, World War One was a European catastrophe, and World War II introduced nuclear weapons and the prospect of civilizational annihilation. The natural progression implies that the next war will be like the previous ones, only “more so.” Hence, fears about the dangers of World War III, even more mass mobilization and conscription, and nuclear war.

This is the world we have been building for two-hundred years, and the world which we increasingly take for granted as “normal.” But this isn’t the default norm throughout history, and as we’ll see, much of history has featured societies where Clausewitz’s triangle is much fuzzier. Ultimately, we’re still buying into 19th century nationalist propaganda if we think a world of platonic nation states and sharply defined national institutions must be the default going forward.

Smaller, expensive, better

In 19th and 20th century industrial war, sheer size and scale mattered as much as did quality. As many World War II buffs will tell you these days, many German and Japanese “wonder weapons” were massive resource sinks which wasted much time and effort. German Tiger and Panther tanks were famously capable, but so mechanically complex and unreliable, and built in such few numbers (just over 1300 Tiger Is, and under 500 Tiger IIs), that their actual impact on the war didn’t live up to the hype.4 In contrast, the American Sherman was easy to build and transport, and also famously reliable and easy to work on, with engines that were familiar to crewmen who had grown up working on farm tractors and trucks.5 In the air, by the middle of World War II, Allied fighter planes were generally better than their Axis counterparts, and were produced in huge numbers. Many allied weapons were well-designed, but critically, they were also well-manufactured. Allied industrial planners knew how not to make the perfect be the enemy of the good.

However, as the 20th century wore on, the ratio between quality and quantity began to change, with increasingly smaller but much more capable numbers of planes, tanks, and ships being produced, and at much higher unit-costs. There was a famous debate within NATO during the Cold War about whether quality or quantity mattered more, with the massive armored formations of the Warsaw Pact giving rise to the saying that, “quantity has a quality all of its own.”

Today, however, “quality” has decisively displaced quantity in every major military around the world (including China and Russia). Tank fleets and air forces that numbered in the tens of thousands during the 1940’s have given way to forces numbered today in the low thousands or even hundreds. Today, the United States military, which spends over $800 billion a year, “only” has 11 supercarriers, about 5,500 planes in the Air Force, and less than 3,000 tanks in active duty (though thousands more are in storage). At the end of World War II, the US Navy had over 6,000 active duty ships. The famous Reagan buildup in the 1980s grew the navy to about 600 ships, and today’s defense-hawks dream of a 300-ship navy which, without unmanned vessels, they won’t get. In World War II, America produced over 15,000 P-51 Mustangs (and similar numbers of multiple other aircraft). Currently, Lockheed Martin plans to produce at least 3,100 F-35 Lighting IIs over a four-decade period, for over a dozen different nations, which will probably be more than any other manned fighter jet this century.6

This reduction in equipment numbers is mirrored in the decline of personnel. The U.S. put 12 million men under arms during World War II, and still maintained over a million men in the army during the 1950’s, and for most of the Vietnam-era. During the 1980s, the army fell below a million, and for the last two-decades has had around 500,000 personnel or less. The Marine Corps today has under 200,000 personnel.

However, despite this reduction in size, militaries today are vastly more lethal. During Vietnam, the USAF launched numerous raids over seven years against the infamous “Dragon’s Jaw” railway bridge in North Vietnam, with little success. Finally a single raid of 14 F-4 Phantoms armed with laser-guided bombs dropped the central span of the bridge, accomplishing what 871 previous sorties, 11 lost aircraft, and hundreds of tons of mostly-unguided bombs had failed to do. Smart bombs and missiles may individually be more expensive than dumb ones, but they also reduce the number of platforms needed (and thereby, the number of lives put in danger). During Desert Storm, the famous A-10 Warthog received praise as the low-tech heavy-hitting close-air-support platform, but high-tech F-111s and F-15Es armed with laser-guided bombs conducting “tank-plinking” missions actually destroyed more tanks. As recently demonstrated over Iran, 19 B-2 Spirit stealth bombers (21 were originally built) represent a global strategic asset.

The same trends towards commonality and modularity we see in the civilian world (smartphone platforms and apps, modular platform manufacturing for vehicles, etc) are in use in the military. The Navy uses one type of Destroyer hull for many roles today, and most aircraft are multirole-capable, replacing specialist-platforms. Stealth aircraft cost more to build and maintain than legacy planes, but require fewer escorts and supporting assets; one stealth platform replacing four legacy ones means one set of spare parts, and one training pipeline for crews. Increasingly, this modularity is moving down to the level of individual missiles and bombs.

Of course, this level of consolidation and modularity does have its limits and risks; a carrier that’s several times more powerful than its predecessors can only be in one place at the same time, and smaller numbers of high-value assets represent putting more eggs in one basket.

Doubtless, as technology and autonomy continue to improve, these legacy higher-value assets will be supplemented by cheaper, more disposable autonomous ones, but that itself is another form of technological innovation, and one which will only accelerate the reduction of the number of humans in direct combat. However, drones and autonomous systems replacing humans in combat isn’t a radical departure, but rather a continuation of a decades-long trend.

Higher-tech means highly-trained

Vietnam was an inflection point for the U.S. military, and the lessons learned in South-East Asia ultimately created the high-tech force of the 1980’s, Desert Storm, and the War on Terror. Greater cost and complexity, however, require more training, and more money spent on personnel. As it happened, the 1980s buildup of a more high-tech and sophisticated military coincided with Nixon ending the draft, and the military shifting to an all-volunteer professional force.

American conscripts in World War II were often given around 13-16 weeks of basic training, and some replacement troops were sent to the front with little more than basic rifle training. Modern troops in most militaries today, however, are often given at least several months of specialized training after their initial boot camp.7 Operating a modern surface-to-air missile battery or maintaining a billion-dollar warship is not simple, and requires a high quality of training, and highly-motivated personnel. Peacetime conscript armies often found that soldiers ended their term of service right as they’d acquired valuable experience, so professional militaries today have longer terms of enlistments, and spend more on personnel (pay, healthcare, housing, etc). While the price-tag of planes and ships garner critics and news headlines, the military actually spends more on personnel each year than it does acquisition (even before housing). Modern soldiers are not disposable cannon-fodder who can be thrown at trench formations as in the First World War, but expensive and highly-valuable assets. Drones and unmanned platforms will only continue to accelerate this trend, as fewer numbers of humans “in the loop” paradoxically become more important on a per-person basis.

An obvious rejoinder to much of what I’ve laid out, is that the U.S. has been on a de facto peacetime footing for a very long time, and hasn’t really had to “gear up,” even for recent wars in the Middle East. In a peacetime environment, armies often get smaller, more bespoke, and expensive on a per-unit basis. And that’s undoubtedly true to some extent. However, the modern American military’s “peacetime” footing isn’t really a scaled down one, but is supposed to be permanently large enough to maintain stability across most of the globe, and deter would-be rivals. The American military isn’t really intended to massively scale up for a major conflict; it needs to be able to fight and win mostly as is.

If necessary, we could of course increase production, and build more planes, tanks, and ships, but the underlying complexity of modern high-tech systems means that there are diminishing returns to mass production. During World War II, The U.S. built dozens of Essex class fleet carriers, which were the most powerful ships in the world. Today, it’s hard to imagine building dozens of 100,000 ton nuclear-powered Gerald R. Ford carriers, let alone quickly enough for them to be used in an active conflict. Modern capital warships are reminiscent of 18th century ships of the line, which at the time, were some of the most complicated things humans had ever built.

Once again, where mass-production might prove most useful, is new versions of more affordable weapons and unmanned systems. There are a fair number of cheap and mass-produceable new bombs, rockets, and cruise missiles in the works or entering service. The debate over supplying Ukraine has also been a wake-up call to Western militaries about the need for deeper and cheaper stocks of artillery and guided weapons.

In theory, of course, the Selective Service System could be used to restart the draft. But the military for which a draft would be used today looks nothing like the military of the early and mid-20th century, and simply isn’t well fitted for it. The most likely scenario for a large-scale war, featuring a conflict between the U.S. and China over Taiwan, would largely be decided by an air and naval campaign, with only limited and supporting roles for ground base forces.8 The U.S. military would undoubtedly expand and increase recruitment, of course, but forcibly calling up millions upon millions of men (and women?) would serve limited purpose.

For context, the 1940 census listed a little over 132 million Americans, and we mobilized about 12 million men during World War II (about 9% of the population). The 2020 Census recorded over 331 million Americans, and we currently have a little over 2 million service personnel, including the National Guard and Reserves (about 0.6% of the population). To equal the World War II mobilization rate, we’d need to put 30 million Americans under arms, a fifteen-fold increase. More realistically, even doubling the entire U.S. military to around 4 million personnel would see about 1 in 82 Americans under arms, a far cry from roughly 1 in 11 in the Second World War.

In terms of paying for a dramatically expanded service, it’s hard to imagine doubling or tripling spending, which is currently over $800 billion, and will very likely surpass $1 trillion in the next few years. In short, unlike in the 20th century, American military today isn’t built to rapidly scale up in size, would struggle to put millions of new conscripts to use effectively, and would have to spend whatever extra money it could get on supplying and reloading the military it already has.

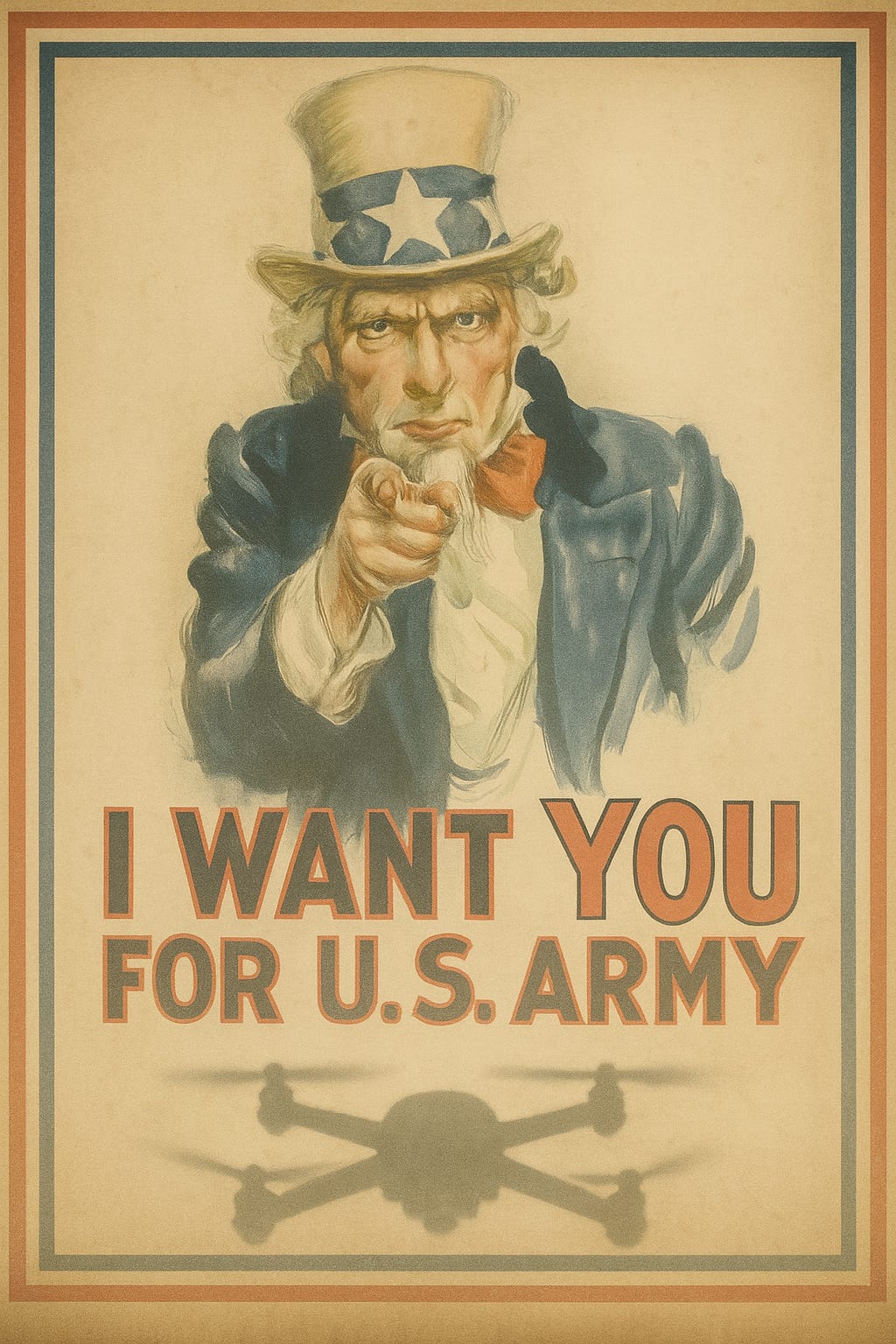

There’s no more “Home-Front”

Recall Clausewitz’s triangle, and the strong relationship between army, state, and people. This triad well explains the importance of “the home front” during the World Wars, where entire civilization populations were expected to contribute to the war effort. In addition to conscription and mass mobilization, civilians were asked to work in wartime industries and ration scarce goods, producing a whole slew of iconic propaganda images and posters. Rosie the Rivetter rolled up her sleeves, Norman Rockwell painted, and even Captain America sold warbonds. Everyone knew someone who served, and usually someone who had suffered a loved one killed or wounded.

19th and early 20th century industrial nation states also had rising demographics and young populations. Fertility rates in Europe and America were well above replacement, and the high birthrates of the late 1800s and early 1900s meant a high proportion of military-age males; the median American was 23 years old in 1900. Pre-industrial infant and childhood mortality had been very high, but improvements in medicine, sanitation, and nutrition saved the lives of millions of children, just in time for them to grow up and be drafted into the largest wars in history.

Today, of course, almost every major developed country (and increasingly, undeveloped countries) have birthrates below replacement level (in many cases, far below replacement level). With falling birthrates, governments have resorted to either overt or de facto policies of immigration to sustain tax bases and fund entitlement programs for increasingly aging populations. Industrial-era nation states could callously view huge numbers of young men as expendable resources. Modern states are already competing for foreign workers, even at the risk of roiling up domestic resentment at home.

Economically, the classic industrial-era nation state saw large percentages of the population grouped into either agriculture or manufacturing. Today, only about 1-2% of Americans are engaged in farming, and about 8% in manufacturing, with the rest spread across a dizzyingly wide array of service jobs which all support each other in various ways. In order to fight an industrial Total War, it was “relatively” simple to draft millions of men, and put most of the rest of the population to work growing food and making the necessary chemicals, steel, and fabric to sustain the war effort. Today, we have much less surplus population to mobilize, and huge sections of the economy that can’t easily be redirected to a war effort, but which remain vital to maintaining the government's tax base in order to pay for a war. Modern weapons also require a vastly more complex supply chain, and an entire digital infrastructure that didn’t exist a century ago.

And of course, America already has a similar debt-to-GDP ratio to that of World War II. Most developed countries (including China probably, when you account for private debt) have similarly large debt. Americans can only buy so many warbonds when we already all have trillions of dollars worth of treasury notes in our 401ks.

Putting all this together, modern nation-states are older, have less available manpower, and in relative terms have fewer readily-available economic and material resources than in the 19th and 20th century. But there’s also the cultural angle.

The decline of a self-assured national culture

The industrial era was also an era of nationalism, mass-media, and patriotism. Governments and elite institutions enjoyed high levels of support and trust, and had reputations for competence and prowess; this was the age of the Hoover Dam, Tennessee Valley Authority, and the first national Welfare programs. Perhaps the most emblematic general of the age was Eisenhower, who in addition to his skill as a politician, was also the consummate bureaucrat, and as President presided over the nostalgic American golden age of the 1950’s. FDR leveraged the national reach of radio for his fireside chats, people all over the world listened to BBC, and the New York Times came as close as it ever would to justifying the slogan “all the news that’s fit to print.” During World War II, the government censored the media, and the media went along. Black and white newsreels before movies showed highlights of “our boys on to victory,” which presented the war in morally black and white terms (in stark contrast to the iconic images of Vietnam and War on Terror, which put so much focus on American casualties). The classic faith and confidence in America of Superman and Captain America come from this period.

It hardly goes without saying that none of this reflects the cultural fabric of today. Starting with Vietnam and running right through to the era of Covid and our current political moment, the American government and elite institutions have taken repeated blows to their trust, perceived competence, and credibility. Congress, the media, academia, and big business are all significantly less popular and trusted today than they were sixty years ago. Today, national expressions of patriotism are less common, and increasingly factionally divisive. Our media environment is fragmented into many different streams and subcultures. In 1983, the series-finale of M.A.S.H. (itself a thinly disguised anti-war commentary on Vietnam) was viewed by 121 million Americans. In 2019, the series-finale of Game of Thrones was watched by 19.3 million people. Popular mass-culture does not exist the way it once did, and is much harder to mobilize or persuade. When Marvel Studios dug Captain America out of the ice and brought him into the present day, his status as a man out of time served as an obvious commentary on how much America has changed.

Ironically, one of the few major institutions which still enjoys a fair amount of trust and popularity in America, is the military. But even as the country retains a mostly-positive view of the military, the average American is increasingly distant from it. Service in the military is increasingly concentrated in regional pockets or subcultures, and many Americans no longer know someone who has personally served in the military. The old national culture of almost universal familiarity with the military has been replaced by the more awkward “thank you for your service” sentiment, extended to a smaller class of individuals that the rest of the country sometimes has trouble relating to.

Another final theme to weave in, is that of “state capacity,” in reference to the relative ability of a government to achieve its desired goals and outcomes. The mid-20th century probably saw the apogee of governmental state capacity, with huge bureaucratic institutions with reputations for competence (this was the era of “experts” in white lab coats after all). This is also the era from which our most iconic dystopian tyrannies come from, including all the visual motifs of Fascism and the Gestapo, as well as the Soviet KGB. The Big Brother of Orwell’s 1984 is a terrifyingly competent bureaucratic institution. Totalitarian states literally ruled “in total.”

Arguably, social media has done much to damage institutional reputation simply by increasing perceived transparency. I’m not sure how well Eisenhower’s administration could’ve handled the age of Twitter and YouTube influencers. Certainly, it seems much harder for governments to carry out large-scale projects than a hundred years ago. Most likely, the future will be one where smaller institutions, leveraging digital platforms, will be much more powerful on a per-person basis.

The state capacity of large national governments may or may not have declined in absolute terms, but they almost certainly have declined relative to the complexity and sophistication of the societies they run. This especially applies to the technology and institutions that undergird modern military systems. Given what we’ve seen with drones in the last few years, I’d wager that a modern tech giant like Apple or Amazon could produce enough hardware in a couple months to conquer a small country.

In sum, Clausewitz’s triangle of state, army, and people is much weaker today, and much less clearly delineated. It seems noteworthy that so many of these transitions all started or inflected around the time of the Vietnam-era. Nixon ended the draft and resigned over Watergate, the military went volunteer and high-tech, and the economy turned global and service-oriented. The earliest versions of the internet were invented in this period, and would eventually lead to the breakup of mass media and popular culture.

China, Russia, Ukraine

If it’s hard to imagine America being able to sustain a mass mobilization of its populace for a prolonged national effort, it’s even harder to imagine most countries in Europe doing the same. In Asia, Japan and South Korea retain strong national cultures, but are aging even faster than Europe. Perhaps one exception is India, which does have a growing population (for now), and a strong nationalist culture.

Even China and Russia, the two countries seen as rivals to Europe and America, are caught up in many of these dynamics. Both are now rapidly aging. But also, both countries have for several decades been attempting to rework their militaries along the high-tech Western model. China is rapidly building a high-tech Blue Water navy, and intentionally leaking images of its 5th and 6th generation aircraft. A US/China showdown over Taiwan will not look like the Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War. While popular images of the Russian steamroller linger on, the Russian military on the eve of its invasion of Ukraine only had about 750,000 active personnel, many of whom were not conscripts.9 Prior to the war in Ukraine, the Russian military had spent a decade attempting to field a whole new generation of high-tech armored vehicles and aircraft.

The current Russo-Ukraine war is simultaneously a fascinating last-gasp of 20th century Total War, and a glimpse of the future to come. If there’s any place on earth where a traditional 20th century-style industrial Total War should still be feasible, it ought to be on the flat plains of Russia’s doorstep. Russia had a veritable mountain of Cold War weapons and ammunition, a much larger population base than Ukraine, and a tradition of mass mobilization and patriotic struggle. Instead, leery of domestic blowback, the Russians have carefully avoided overt mass-mobilization of the entire populace, relying on contract troops, even foreigners, and not just from North Korea. The Russians have exhausted much of their Cold War stockpiles, and have had to import artillery shells from North Korea (whether these are pass-throughs from China, I have no idea). Even the Russian’s own best-case statements about armored vehicle production mostly involve refurbishing mothballed vehicles, and not large numbers of new tanks and armored personnel carriers. And for all that the Russians have thrown at Ukraine over the last three years, their advances most days are measured in the hundreds of yards at best. In a far cry from the days of Soviet “Deep Battle” doctrine involving the 1st Guards Shock Army, many Russian assaults on Ukrainian positions are carried out by small squads dashing forward on Chinese-made dirt bikes, attempting reach Ukrainian trenches before Ukrainian drones and artillery reach them.

The Russian military is not incompetent, and has learned quickly, pioneering among other things fiber-optic guidance cables on drones to avoid jamming. But the old 20th century Total War playbook hasn’t worked for Russia. Modern guided weapons and ever-present reconnaissance from drones and satellites have made it nearly impossible for an army to move openly within several miles of the front. I’ve looked several times over the last couple of years, and I cannot find a single instance of a traditional armored breakthrough that even Russian sources can point to as a success.

Ukraine by contrast, has blended elements of 20th century Total War, along with a rapidly emerging picture of what war in the future may well look like. On the one hand, Ukraine has called up reserves, mobilized much of its population, and seen a remarkable outpouring of national unity and solidarity, reminiscent of the 19th and 20th century. It would be a great irony if Russia’s attempt to deny Ukrainian national history and reabsorb its former satellite, ultimately ends up producing a dramatic ethnogenesis and strengthening of Ukrainian statehood.10

On the other hand, Ukraine has, for most of the war, relied on older veterans with previous conscript experience, and has actively avoided drafting its entire population. Ukraine only lowered its minimum conscription age from 27 to 25 in April of 2024. In what should be one of the most clear-cut cases of national mass-mobilization in recent history, Ukraine has still not even tried to draft its 18-year olds. Of course, it’s possible that the pool of 18-year olds is not very large (many having already volunteered or left the country). Ukraine’s official rationalization of this policy is that older veterans on defense are steadier and more reliable, and that they want to preserve their younger population for the future. Either way, declining demographics drive a different logic when it comes to staffing a modern military, even in a national crisis.

Instead, Ukraine has fended off the Russian steamroller by leveraging technology and the social institutions which undergird rapid innovation. The list of Ukrainian achievements and innovations here is much longer than just the headline claims about drones now causing 80% of Russian casualties. Early on in the war, the Ukrainians used some of the same off-the-shelf programming architecture found in Google Maps, to put together an “uber for artillery” network, that could dynamically task artillery fires to the most high-priority targets in under a minute. Unmanned ground vehicles are starting to carry reinforcements, supplies, and remove casualties from the lines. Videos of FPV drones knocking down other drones by ramming or fouling propellers are no longer a novelty, and more sophisticated interceptor drones are starting to supplement traditional surface-to-air missile batteries against Russian Shaheds.

In less than three-years, Ukraine has developed, built, and launched an indigenous drone/cruise missile campaign that routinely strikes industrial and military targets deep inside Russia. Twenty years ago, only a handful of countries on earth had such a capability. In 2011, one of the reasons the Europeans asked for American assistance in Libya was that the French and British didn’t have enough precision weapons to reliably destroy Moammar Ghaddafi’s obsolete air defenses.

Beyond weapons systems at the front, Ukraine has been able to cobble together much of the digital command and control communications systems as traditional armies, for a fraction of the cost. SpaceX’s Starlink satellite terminals provided crucial communications bandwidth early on in the war, and with updates have apparently proved resilient to Russian jamming. There are many pictures and photos of Ukrainian command posts using Discord servers (as in, the gaming chat platform) to communicate with units. One of the most remarkable innovations is an online digital marketplace, where Ukrainian units post verified videos of killed or damaged Russian forces, and earn gamified points that they can use to purchase equipment. The system incentivizes Ukrainian troops to compete for kills and rewards, lets units choose which equipment they most think they need, and bypasses many traditional procurement bottlenecks and inefficiencies. Maybe it will turn out that the most realistic thing about the Call of Duty franchise of video games was global leaderboards and killstreak rewards.

In conclusion

Although it has elements of traditional 20th century Total War, the War in Ukraine also shows how much war has already changed. While drones get all the attention, what's more important is all the changes that underpin them. Useful weapons no longer need bleeding-edge technology and R&D labs, but can be had for the cost of off-the-shelf motors and the processing power of a cheap smartphone. As long as the coding prowess to resist jamming and hacking is present, civilian messaging apps and internet terminals can fulfill the same role as bespoke command-and-control infrastructure. Some of the most valuable individuals in this war are software programmers, small engineering teams copying Silicon-Valley’s startup-culture, and 20-year old gamers turned-FPV drone operators.

A large war between the U.S. and China wouldn’t automatically look like Ukraine, and in fact, I think Ukraine may be a bit of a false dawn for drone warfare in some ways, as I hope to discuss in the future. A naval war over Taiwan would look very different, and would leverage very different capabilities (short-range FPV drones cannot sink aircraf carriers). But those differences will still draw on the same changes in the modern world, which no longer make 20th century Total War a good blueprint for thinking about largescale conflicts.

So if “World War III” as “World War II but more so” is a bad way to think about the future, what historical parallels should we look towards? For all the talk about warfare changing in “unprecedented” ways, there are actually plenty of old wellsprings we can draw on to help us make sense of the future. In more than a few ways, a world where Clausewitz’s triangle is breaking down, is actually a return to something old. That will be the theme of a sequel to this piece.

We’ll set aside the question of a full-on nuclear exchange for now, and focus more on conventional war. Frankly, it would be hard to organize a draft in such a case anyway.

Late in the war, crews on USN carriers were sometimes known to simply push damaged aircraft overboard rather than bother with repairs, since so many replacements were readily available.

Clausewitz was a good 19th century German, who thought much about ideals and how to get as close to ideal states as possible. 19th century German philosophers tried to define the perfected nation-state as the end product of History, and Clausewitz attempted to define the platonic form of warfare.

By at least one estimate (there are others, but the ratios are similar), A Tiger tank took about 300,000 man hours to produce (much of it by hand), whereas a Soviet T-34 took about 30,000 man hours to produce, and an American Sherman, just 10,000 hours.

Old stories about the Sherman being a deathtrap are mostly a myth.

The F-35 has something of a (partly earned, parly exagerrated) reputation as a boondoogle, but with a unit cost of under $100 million, its both cheaper and more capable than most of its Western-built competitors.

Veteran Ukrainian units sent to Europe and America for training on new platforms still took several months, despite stories of their host trainers being surprised at how quickly the Ukrainians learned.

The U.S. Marines have ditched all their Abrams tanks, and are rebuilding themselves around the concept of island-hopping across the South-China Sea in small groups, deploying pop-up missile batteries to ambush PLAN air and naval assets.

One of the reasons some Western analysts were caught flat-footed by Russia’s invasion in 2022, was that the public estimates of about 200,000 troops along the Ukrainian border, weren’t big enough for a full-scale invasion and occupation of Eastern Ukraine, but did represent a very large percentage of Russia’s ground forces.

The year before the invasion, Putin published a massive essay on the history of Ukraine and Russia, basically laying out his case for why he believed the existence of an independent Ukraine was a mistake and accident of history. Along with corruption and logistical woes, the simplest explanation for the failure of the initial Russian invasion was that Putin mistakenly believed his own cherry-picked history, and thought that he just needed to quickly occupy Ukraine’s political centers, where Russian forces would be welcomed.

Most terrifying part about all this to me, is that democracy and rights for the common man seem to be correlated with mass mobilization actually being useful for war.

a very pleasant read!