The Polis of the Educated

Liberal education and its challenges and opportunities in the modern world

This is part three of a series of essays on liberal education and its value today. Previous installments are here and here.

I can imagine a few possible rejoinders to the argument I’ve made for liberal education, including charges that a classical liberal education is elitist and promotes Western exceptionalism, and is not suited to a world of multiculturalism and diversity. I think these critiques are either misplaced, or can be answered and addressed. In answer to possible fears that the modern world lacks a unifying telos around which to build such institutions, I think there are important historical precedents to learn from. Finally, I think the value of having an old and venerable tradition to build upon is perhaps even greater than we might think.

Classical Liberal Education does not own the True, Good and Beautiful

Classical liberal education may for some connote elite snobbishness and superiority, calling to mind a world of pretentious boarding schools (all-male of course) and stuffy intellectuals looking down their noses at those who can’t conjugate Latin verbs or quote Cicero. If liberal education is so excellent, what are we implying about the vast majority of people who don’t have it? If the small coterie of liberal arts colleges and secondary schools are turning out such excellent students with well-formed souls, does that make everyone else a sort of second-class individual of lesser worth? Although, if that were the case, why then did liberal arts education ever fall out of favor in the first place, and why aren’t liberal arts students about to take over the world and run things again? Modern liberal arts educators and advocates might pause a moment here and cultivate another virtue, that of humility.

In answer to this objection, I would suggest that perhaps liberal arts education does not in fact possess a sole monopoly on teaching the best way to live, and that one can find a great many skilled and talented athletes, business leaders, intellectuals and academics, and artists, in the world today. Many modern books teach their own versions of the great lessons on self-control, knowledge, wisdom, and appreciating beauty, and in fact, this should not surprise us. If we think that the liberal arts tradition is good and useful because it first reflects that which is True, Good, and Beautiful, and that the Transcendentals exist independent of any particular tradition, then we should expect to find that others might happen upon glimpses of this same True picture of reality. There are many liberally educated souls who have become free and self-mastered without having had Latin verb endings drilled into them in secondary school. Healthy traditions are living and dynamic things, and constantly adapt to new times and places, taking in new influences and inspirations, without deviating or changing from their core foundations and principles. Just as medieval and renaissance literature was added to the corpus of learning, there will certainly be contemporary movies, art, and literature which will one day enter the canon of great works.

The case I would make for studying the classical liberal arts is not that it inherently makes anyone better or superior solely by virtue of entitlement. Instead, a well-worn tradition is more likely to have had a great deal of experience overcoming challenges and solving problems, eliminating dead-ends and unhelpful ideas, and determining the best ways of doing something. A modern person could probably recreate many of the same virtues, good habits, and pieces of wisdom based on what they might find in society around them, but they will likely get further and faster leaning on the resources of an existing tradition, so long as they put forth the required effort.1 It’s harder to reinvent the wheel on your own.

Classical Liberal Education After “Western Civilization”

But what if the wheel is also rotten or even evil, and needs to be thrown out? Liberal education is embedded in Western Civilization, which for some raises the specter of imperialism, colonialism, and even fascism. If liberal education describes students in British boarding schools memorizing the Julio-Claudian family-tree and chanting Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome, then does it also endorse European imperialism and the paternalism of Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden?” Aristotle thought that women had fewer teeth than men, and his views on natural servitude were used to justify chattel slavery in Africa and the New World. Julius Caesar may have killed a million Celts in Gaul, Alexander the Great conquered empires out of vainglory, and the Crusaders splattered blood up to their knees as they rode through the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, slaughtering Muslims, Jews, and Christians alike. If we take a hard look in the mirror at Western Civilization, we might not like all of what we see.

But who made the mirror in the first place? The means by which the modern world condemns racism, imperialism, and various forms of oppression, are themselves classically liberal. Individual dignity, freedom and self-determination, tolerance for the minority (ethnic or otherwise), equality before the law, and the rule of law itself, all find their best expressions within the classical liberal tradition. Martin Luther King referenced Socrates and appealed to Augustine and Aquinas in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, and understood the Declaration of Independence as a promissory note to African-Americans that America was obligated to honor. Similarly, the success of Gandhi (a Western lawyer before he was an Eastern holy man) and his quest for Indian independence rested upon a free press, cosmopolitan international audience, and the ability to hold the British Empire accountable to its own moral standards. The Western intellectual tradition offers tremendously powerful tools for self-reflection and self-criticism, in a line running back to the Oracle of Delphi’s admonition to “Know Thyself.” Moral self-interrogation, reflection, and reform according to the dictates of reason and justice, are not just things which can be applied to the western tradition, but are fundamentally part of that tradition in the first place.

In 1900, “Western Civilization” was a triumphalist concept sometimes applied broadly and arrogantly onto the success of Europe and North America as an explanation (and justification) for imperialism and ostensible scientific and moral progress. That hubris met its nemesis in the trenches of The War to End all Wars, and again during an even greater war three decades later. Setting aside all complicated theories about Marxism and postmodernism, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that Western Civilization is undergoing a century-long crisis of confidence, questioning and doubting its fundamental assumptions. Having lost a clear and coherent sense of what humanity and the Good Life means, the remaining impulse to criticize and self-interrogate runs the risk of becoming a civilizational auto-immune disease.

Is classical liberal education then part of a project to “reclaim” or rebuild the West? If by that one means to turn back the clock or attempt to restore some sort of previous order or hierarchy, then I think not. Regardless of what we might think of the merits of such a project, its prospects seem to me rather dim, and also entirely beside the point when discussing contemporary education. Any new movement or institution, in any time and place, cannot help but reflect the context of that time and place, even (and perhaps especially) if its aim is in opposition to an existing order; the Protestant Reformation cannot be defined without also mentioning medieval Catholicism. Western liberal education, at its best, has always aimed at something timeless. Maintaining a living link to an older tradition is a healthy grounding practice, serving as a callback to previous eras and habits of order; touchstones and signposts showing how others have tried to reach up towards the transcendent. But to attempt to go back in time and recreate a previous habit of being is to go in the wrong direction (literally, as you’ll be traveling back down a path, instead of forward and away from what came before). Past societies were moving in their own directions and trying to respond to their own past challenges and problems that were different from our own.

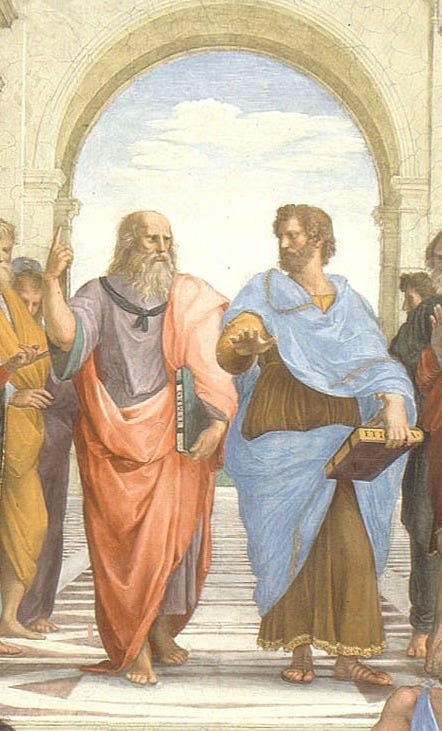

But in any case, despite the fact that classical liberal education draws from the past, its institutional habits have constantly been adapted and crafted in response to the challenges of its day. Plato’s Academy, the Medieval scholastic, the Renaissance humanist, and the Victorian boarding school might have all been engaged in something called “liberal education,” but the differences in their cultural backgrounds and philosophical goals and ideals become starkly apparent once you pause and think about them. Each was suited to its time, place, and circumstances, and any classical liberal arts school in the 21st century ought to be doing the same thing. What each tradition does have in common, however, is a quest to see and understand reality as clearly as possible, and then to live in that world, aiming towards some vision–constantly shifting in and out of focus and changing its apparent colors in the light of the times–of "The Good Life.”

So a classical liberal arts education in the 21st century need not be reactive and backwards looking. But can assertions of transcendental goods and “the Good Life” be compatible with 21st century secular society? We often think of the pre-modern world as more homogenous, and embracing of tradition. The modern world, by contrast, is complex, diverse, individualistic, and skeptical. A bygone view of “the Good Life” based around a concrete set of virtues and values still seems stuck in the past, or reflexively at odds with a modern world that embraces tolerance and open-ended self-fulfillment without a higher telos.

Once again, I think traditional liberal education is better suited to our moment than one might think. Most importantly, on the concept of objectivity and absolutes, I will grant that one of the common through-lines across most forms of liberal education has been a belief in capital-T Truths, putting the tradition at odds with pure relativism. And yet, while liberal education has maintained that something called Truth, Beauty, and Goodness exist…there’s quite a lot of arguing as to exactly what those transcendentals look like in practice. Any genuine exposure to “the great debate” across the Western tradition (and, I would hazard, across the various canons of Eastern literature and philosophy as well) should always emphasize just how much various great thinkers actually disagree with one another. The Great Books canon is full of disagreement, in a line of inquiry running back to the start of Western philosophy itself. Socrates was hailed by the Oracle of Delphi as the wisest precisely because he was so aware of his own ignorance. Plato’s dialogues have many more questions than answers, and knowing how to ask the right questions is a useful ability in a complex world full of differing perspectives. One of the great tasks of any educator is to first teach students that something important exists, and then that the student does not know what that thing is. Many of the greatest experts are often the most humble about what they don’t know.

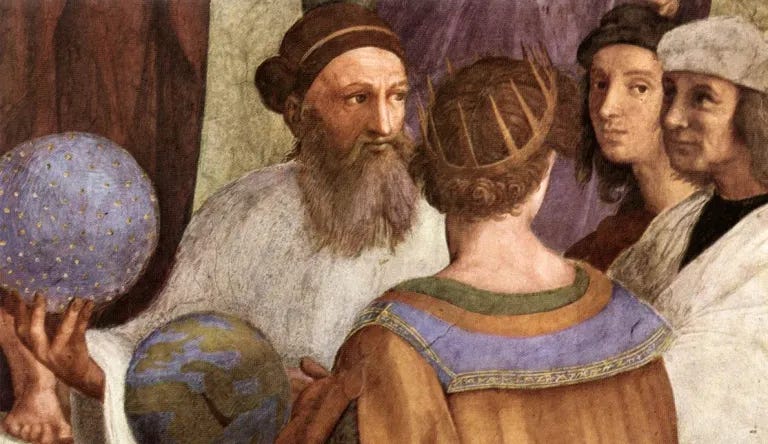

Not only is a good liberal education not dogmatic and one-size-fits all, but it is usually cosmopolitan and broad-minded. Ancient cities were themselves full of many different cultures, ideas, religions, and attitudes; Alexandria was arguably one of the most multicultural cities in the ancient world, and was famously home to many different philosophical schools. In fact, the places in the premodern world which foreshadow the modern world the most (urban, commercial, cosmopolitan, literate, malleable, more democratic, and often chaotic), were generally the places most alive with liberal education. The medieval monasteries were exceptions to this pattern, but monasteries were also centers of economic innovation, and jump-started the growth of towns and urban centers. And as soon as medieval Europe could support larger cities, universities sprang up within them.

Traditions of Inquiry Competing with Each Other

For that matter, those medieval universities went through an intellectual crisis and revolution not entirely dissimilar from our own. The arrival of Aristotle and other classical texts from the Byzantine and Arab world shook up the Neoplatonic Augustinian tradition of Western Christendom, and required a great deal of work to reconcile, resulting in the grand synthesis of Thomistic philosophy. A few hundred years later, that same Scholastic edifice was challenged and partially-overthrown by the Scientific Revolution. At our modern remove, these intellectual crises and revolutions sound rather tame and part of the “just-so” story of intellectual movements, but this does a disservice to the historical actors involved. Galileo and Copernicus’ challenge of the Ptolemaic model of the universe meant much more than just the relative position of the Sun; it ruptured an entire cosmos. Here and now, it’s easy to imagine that the intellectual challenges and problems of the modern world and tradition are irreconcilable. But a 13th century Parisian might have thought the same of the teachings of Averroes and the Siger of Brabant.

While our current controversies of science, nature, identity, and meaning may prove impossible to resolve, there is often an egotistical despair in the phrase “this time, it really is different.” If nothing else, such competing ideas and traditions can serve as intellectual sparring partners, helping hone and sharpen our own traditions, and perhaps preventing too much internal navel-gazing and introspection. From its beginning, the best of liberal education has had an eager openness for new ideas and influences; at the start of the Republic, Socrates has just arrived from the Piraeus, Athens’ port, and declares that the Thracian festival (which his audience would have understood as, at best, semi-barbarous) he witnessed was as beautiful as the local one. One of the first pre-Socratic philosophers was Thales of Miletus, who learned wisdom about geometry and astronomy from the East. While one classical historiographic tradition portrayed the East as a world of oriental despotism and tyranny, another has always seen the far East as a world of wonder, wealth, and knowledge; Marco Polo travelled to the center of the world, not its backwater.

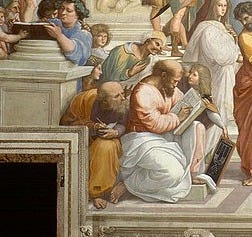

In college I had a professor who, while explaining the scholastic tradition of Thomas Aquinas, emphasized this spirit of open inquiry for the Truth, building on Plato’s point that to learn something and be cured of error is always an improvement and a gain. The Professor told a story about two priests visiting Galileo while he was under house arrest, and arguing with him about heliocentrism. The story ended with Galileo begging the priests to simply look in his telescope and see the evidence for themselves, but the priests hung back, afraid to confront their possible error. My professor declared that Aquinas would have bowled over those two priests and knocked them aside in his rush to look in the telescope and see for himself, because Truth is always good, no matter where it is found, and it is a mark of confidence to seek it out.

So, if there was an arrogantly triumphalist tone in “Western Civilization” before World War One, perhaps a competitive world of clashing traditions and ideologies may be good for liberal education, in the vein of iron sharpening iron. If we believe in the pursuit of Truth, then we must pursue it everywhere. If it is True and Beautiful, it will be Good. If what we believe is in some way erroneous, then we can only benefit from the correction.

The Postliberal Critique - Society without the Summum Bonum

But the rejoinder that might well be repeated that the modern world lacks any notion of the Summum Bonum, and a common vision of what human eudaimonia ought to look like. Instead, the world is a sort of hyper-Lockean open-ended pursuit of progress and self-fulfillment, with no limiting principle or teleological end, and the only goods which remain are choice and consent. Aristotle talked about the common good of the polis, and medieval Christendom pursued the Kingdom of Heaven, but Thomas Jefferson gives no definition for the pursuit of happiness. With no common vision of the Good Life, no true commonwealth or political order in the Aristotelian sense can properly exist. We are just individuals aimlessly consuming, and have been liberated far too much from nature, community, and genuine meaning. Socrates may have questioned the truth, but he clearly lived in an established social order with commonly accepted beliefs and pieties that could be questioned in the first place.

I think some of these postliberal critiques of the modern world need to be taken seriously. The tremendous changes the modern world has gone through in the last two-hundred years call for some humility and caution; we don’t yet know the long-term consequences of a world predominantly urbanized, wealthy, technologically complex, and ever-changing. Deracinated rootlessness and anomie may be real social ills that need addressing, and rival systems of morality, culture, and education may need to hash out Live and let Live compromises. Perhaps Red and Blue-state America will need their own Peace of Westphalia. At a certain level, on the larger philosophical and political challenges of the modern world, I think I’ll have to punt the question as above my paygrade and purview.

A big reason for wanting to punt the question away however, is because I think there remains so much space for meaningful action and institution-building within individual schools and communities, and that if classical educators believe that their vision of the Good Life really is the healthiest and most useful to the rest of society, then the best way to garner support is to simply go out and do it. Once again, there’s an important historical precedent to build on here.

It’s actually not hard to take the accusation that the modern world is too big, rootless, and bereft of meaning, and apply it back on the Roman Empire at its height. Aristotle had envisioned that a true political community needed to be small enough for the participants to really know one another, and that a genuine polis must be self-governing. A city ruled by another power was not, at the end of the day, a true political community. And yet, for the better part of six-hundred years following the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean, the communal life of the ancient polis continued to flourish; a fact often glossed over in our survey courses of the period. We talk about the whole world “becoming Roman” and gaining Roman citizenship, and Hadrian building a Pantheon to symbolize that the empire was a universal civilization. Romanization was central to the empire’s legacy and inheritance.

And yet this world was also (across most of the Mediterranean) still Greek. Underneath the mantle of the universal city, Greek-style poleis’ continued to practice assembly-politics and elect aristocrats to city councils who vied for status by passing laws, fostering patronage networks, and endowing temples and public buildings for the sake of popular acclaim and the chance to have their name memorialized in stone for future generations. Roman Emperors generally had better things to do than micromanage the affairs of local cities, which remained in important ways, largely self-governing. Indeed, one of the criteria for colony settlements to become full municipia was the adoption of a regular constitution and the holding of elections. The identity of being an Athenian vs. a Corinthian or an Ephesian still mattered to local citizens, although such rivalries mean little to us today, and so are often forgotten. Plutarch intended for his biographies of the great classical statesmen to serve as models for his own aristocratic peers, and in his essay giving advice to young leaders, echoed the same famous Periclean and Ciceronian themes of the civic noblemen in service of the common good. And, while acknowledging that leaders will have to account for and sometimes reckon with the imperial superstructure above them, it’s clear that Plutarch believed that there remained plenty of meaningful space for political action and public virtue within the ancient city-state.

Such layered identities, where one could participate in multiple social orders at the same time, even existed within individual cities. A very large metropolis such as Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, or Constantinople had multiple neighborhoods and districts segmented by ethnicity, religion, or economic association. To say that Alexandria was Jewish, Greek, and Egyptian, was really to say that at least three separate polities were jammed together inside one larger identity, each of which looked after most of its day-to-day affairs by policing crime, regulating economic life, and negotiating with other groups. These neighborhoods could often be, as in the case of Constantinople’s circus gangs and Alexandria’s mob, inflammatory and violent. But these cities were also the most fecund, creative, and dynamic places in the ancient Mediterranean world, and their neighborhoods helped recreate much of the tighter communal identity that Aristotle had credited to the original Greek polis.

Although the ancient city-state declined severely during late antiquity and the early middle ages, it survived in the Byzantine Empire and Arab Caliphates, and then revived in Italy during the High Middle Ages, ultimately leading to the Renaissance. Northern Europe had its own thriving city-state culture in the imperial free cities of the Holy Roman Empire, the Low Countries, and the Hanseatic League states in the Baltic. The enduring importance and centrality of the city-state in Western history remains popularly underappreciated, due to the lingering emphasis since the 19th century on national histories of Europe and North America.

So there is ample precedent for groups of individuals to form intentional communities and institutions layered in alongside other communities underneath a larger societal superstructure, and America’s traditions of federalism and localism are, to put it very mildly, not unsuited to such an environment. While the high-level philosophical questions about national politics and a common vision of the Good aren’t unimportant, it is in local communities and institutions that most humans actually live and thrive. As long as freedom of thought, speech, and association (values which our Lockean “live and let live” social contract still protect above all else) remain, classical liberal education remains viable as a method of instruction and formation.

The Greatest Good is to Discuss Virtue Every Day

While there should be some sort of alignment between the teleology of education and the teleology of society (well educated souls ought to work towards the eudaimonia of society), aligning those goods in practice is probably about as difficult and fraught with danger as aligning politics and religion. Education, like religion, must always orient towards the perceived good in the highest and most absolute sense, while politics is necessarily prudential and constrained by compromises and necessary evils. Education, like art, is more severely damaged when corrupted away from Truth and Beauty and towards propaganda, while politics is frequently the art of having to make the least bad choice available. Philosophy and politics always exist in tension and even conflict, with noble lies and Straussian interpretations abounding in the works of great thinkers. Pursuing the True, Good, and Beautiful can actually be quite radical and dangerous. Socrates was not the only martyr to philosophy.

In fact, the central fame of Socrates as the self-mastered free soul refusing to bend to the will of the mob is made possible by this very tension between education and the polis. In the Apology, Socrates famously says that “the unexamined life is not worth living” as he explains why he will never stop practicing philosophy, even on pain of death. In the Phaedo, his death scene is clearly presented as a victory, where Socrates frees his soul from the shackles of his body, and meets his end on his own terms, with courage and equanimity. The final test of the liberally-educated is to die a free person, and not a slave to fear.

Yet there is more to the “unexamined life is not worth living,” quote, often neglected. The extended quote is, “I say that it is the greatest good for a man to discuss virtue every day and those other things about which you hear me conversing and testing myself and others, for the unexamined life is not worth living.”2 We should examine ourselves regularly, because to live in a state of stupor, mindlessly working and consuming, is not to be fully human. But the examined life must be done in community, in a common fellowship eager for a vision of the Good Life and its attainment. It is our family, friends, colleagues, and fellow students who know and trust us enough to let ideas, thoughts, and struggles come to light in moments of intellectual intimacy, where they can be rebutted, expanded, refined, and acted upon. The mount of wisdom that is Reality is a harmonious unity approached from different directions by each discipline of knowledge, and by each individual within those disciplines. Daily, it is our friends and trusted companions who help us see Reality through the fog of our weaknesses, limitations, and foibles. One eye can sense the light, but a second pair gives depth and clarity of focus.

Describing liberal education this way, as small, intentional communities rigorously pursuing the virtues together according to a shared vision may lack the elevated mystique and sophistication of Oxford professors in wood-paneled rooms spouting off translations of Homer and Virgil. But Greco-Roman philosophy, Medieval scholasticism, renaissance Humanism, and the American schoolhouse, all started off as small and half-formed projects groping their way forward, based mostly on hard labor and old wisdom. A system cannot work at scale if it can only be organized and led by a very small number of geniuses; while we can talk about the concentration of talent in Charlemagne’s Aachen, or 15th century Florence, these models soon spread all over Europe, and had to work even in the hands of very pedestrian schoolmasters.

This probably helps explain some of my very own feelings of imposter-syndrome as a new teacher, over a decade ago, burdened with a weighty and genuinely noble task, and very conscious of my real (and perceived) inadequacies. A good teacher must be an above-average individual in several categories, but truly outstanding talents usually go on to more lucrative or rarefied careers. While my school has enjoyed very gifted leadership, my campus is mostly staffed by liberal arts graduates of schools like the University of Dallas, Baylor, and Hillsdale, who are knowledgeable, dedicated, and eager for their craft, but not so unique that our success cannot be replicated, as indeed it is at other classical schools. Across the various home, private, religious, and charter networks, classical schools are currently educating hundreds of thousands of students, and there is no reason that number cannot grow into the millions within a decade. I already have former students that are now my colleagues, and they are better third-year teachers than I was in my fifth.

The Polis of the Educated

The “classical” element of liberal education has been extraordinarily useful, as it provides the old wisdom around which to coalesce the hard labor of institution-build-ing. All other things being equal, we ought to expect that things which survive for a long time should have some useful skill or worthwhile quality which proffers some advantage, in the same way that pre-modern communities valued their elders for their experience and wisdom. Many of my very best lessons as a teacher are not my own, but were given to me by Thucydides, Plutarch, and Boethius. It’s easier to teach a very good book than a mediocre one, and the fact of the internet means that teachers and scholars are no longer limited to only those books and mentors that they can access physically. The very fluidity of the modern world paradoxically means that a teacher can access the strongest canon of great ideas (both modern and ancient) in history. The fact of a two-thousand year old tradition in continuous dialogue also strengthens the communal aspect of a shared vision for the goals of education. Not only are we viewing the mountain of Reality around the points of the compass, we also get a glimpse of it across time itself, not in three dimensions, but four.

A thriving liberal arts school is part of a larger eudaimonia-seeking body connected across time and place, and the classical tradition gives definition and direction to its shared identity linked across the generations. Ancestral statues, stories, and traditions guided the aspirations and moral actions of Greco-Roman citizens in a polis, and the great works of literature, art, and philosophy can help shape the aspirations and moral actions of modern students today. Although its offer of citizenship is not always accepted, this tradition offers, in return for inquisitiveness and perseverance, membership into that polis wherein all citizens are free, and freely educated.

The Apology, 38a - G.M.A. Grube Translation

i’m stuck on whether or not societal eudaimonia is achievable in a culture as hyper-individualistic as ours, and also in awe because your writing is so so good