The Iconic Status of D-Day

On what may be the single most complex and difficult undertaking in human history

One personal consequence of being held in fascination with history, is that you watch the fading of memory over time, as events decline and pass out of popular consciousness. When I was a child, newspapers and documentaries channels regularly marked the anniversaries of famous WWII events such as Pearl Harbor and D-Day. Today, I’m the teacher grousing to students that they can’t forget December 7th and the day of Infamy. Unfortunately, school is out in June, so I can’t also remind students about Midway (June 4th) and D-Day (June 6th).

But this year marks the 80th anniversary of the Normandy landings, and I’ve seen news stories about the few remaining veterans flying over to France, which is hosting a week’s worth of events commemorating the battle. If you’ve never seen footage of French civilians rubbing sand from Omaha beach into the letters on the tombstones of the fallen, it’s well worth taking a moment. Against the white marble, the sand emerges golden.

As popular knowledge about the second world war continues to fade, fewer events remain. Probably at some point, if not already, many Americans will be hard pressed to identify much more than Pearl Harbor, Normandy, Hiroshima, and the Holocaust (this isn’t meant as a lament about American education but more as an observation on the erosion of popular memory). Interestingly, Normandy is the only one of those events remembered simply for being a battle during the war. Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima marked the beginning and end of the war, and the Holocaust speaks for itself. Somehow, Normandy is similarly iconic.

Operation Overlord

The allied invasion of Western Europe was not the largest battle of World War II, nor was it the most decisive. Multiple battles in Russia were larger and more destructive. In addition to the famous battles of Stalingrad and Kursk, Operation Bagration began soon after the Normandy landings, and resulted in the Red Army completely rupturing the Ost front and causing over a half a million German casualties. Even in the context of the Western theater of the war, the allies already controlled most of the Mediterranean, and had liberated Rome two days before the Normandy landings. The Western allies had a clear material advantage over Germany, and the strategic air campaign had spent the first half of 1944 tearing the heart out of the Luftwaffe. The D-Day landings were just one of many tipping-point moments in 1944.

Yet this does not diminish the landings, or take away from their unique status. D-Day deserves to be remembered long after the last veteran of Omaha beach passes away.

Overlord was the culmination and final realization of a great many other events and efforts throughout the war, and was essentially the pivot point of the entire allied strategy from the moment America entered the conflict. For all the truth to the fact that the greatest amount of fighting and casualties occurred in Russia, Stalin still spent much of 1942/3 pleading with Churchill and Roosevelt to open a second front as soon as possible, in order to take pressure off the Red Army. While the strategic bombing campaign eventually did significantly damage German industry, its most direct accomplishment was giving the allies command of the air, without which a cross-channel invasion would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. The Mediterranean campaigns protected British Egypt and the Suez canal, and knocked Italy out of the war, but also crucially served as test cases for large-scale amphibious warfare. Many lessons were learned the hard way during the lower-stakes landings in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy.1 In hindsight, it appears remarkably naive that US Army planners ever even considered a cross-channel invasion in 1942. But even this naivete highlights how the invasion of France was the focal point for the allied strategy in Western Europe. Almost everything led up to Normandy, and the downfall of Germany in the West flowed from it.

I think the Normandy landings have to be considered as a contender for the most complex event in human history, though I cannot here consider every competing entry to definitively rule all other events out. I don’t have a specific source for this claim, so I’m open to correction or alternatives. Obviously, the Manhattan and Apollo projects were technically more challenging, but they involved smaller and more streamlined institutions. Even though campaigns such as Operation Barbarossa (Germany’s invasion of Russia) and the German invasion of France in 1914 involved more forces and much larger battle spaces, Normandy presented uniquely complex challenges on a tremendous scale. I’m hard pressed to think of a specific event occurring at a distinct time and place in history that required more detailed and intricate planning, preparation, and organization, and I think you can get a sense of this if you look at the Normandy landings from the perspective of amphibious operations, multi-domain operations, and finally, as a joint allied operation.

Allies and logistics across air, land, and sea

Until the 20th century, military history doesn’t actually have all that many large scale contested amphibious operations. While localized raiding, piracy, and amphibious sieges are common enough in the historical record, large movements of armies and follow-on forces sufficient to take and hold large territories usually required unopposed landings, preferably at a port or harbor. Ports and harbors were usually required, even though ancient and pre-modern armies didn’t need the continuous quantities of fuel and ammunition that industrial armies consume. Directly contested landings in the face of determined opposition on the beaches, such as Caesar’s invasion of Briton, aren’t all that common.

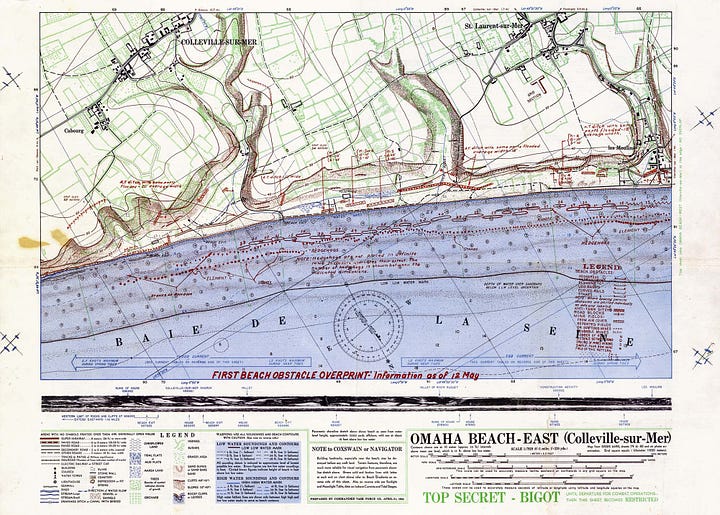

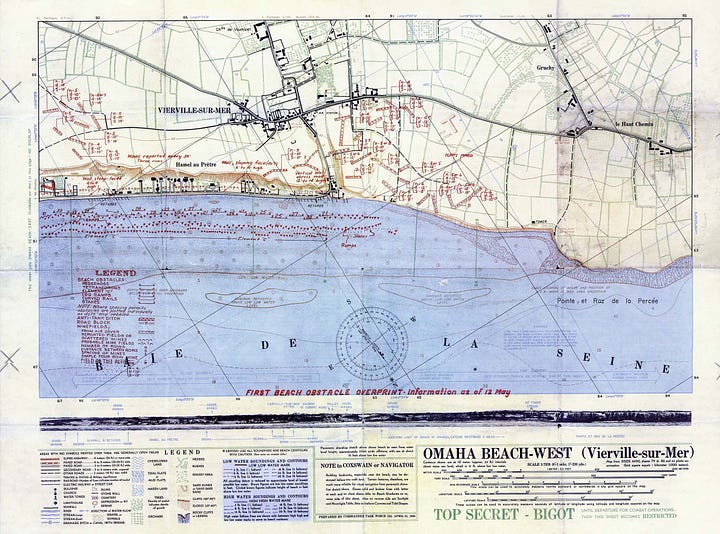

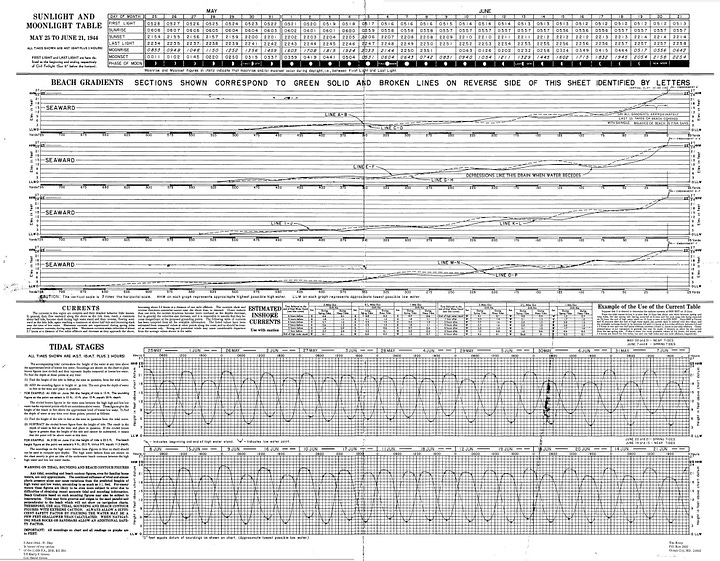

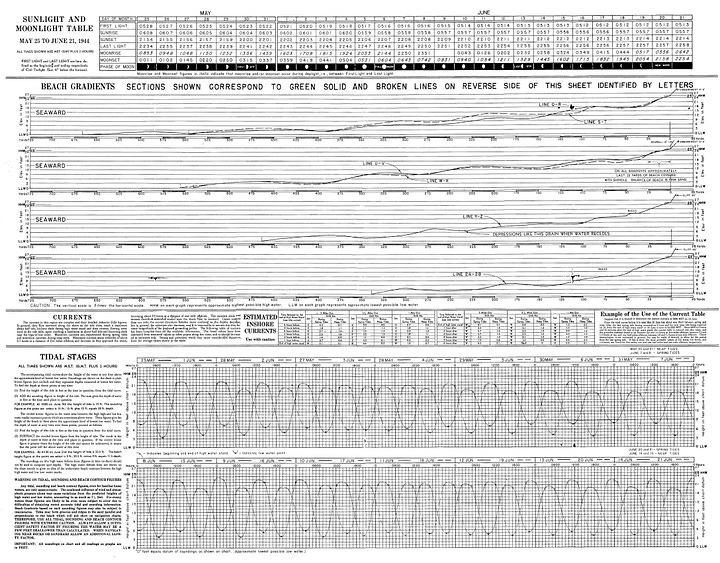

Moving tens of thousands of men and supplies over any distance is a remarkable feat, and one of the most important developments of modern warfare was Napoleon’s introduction of the corps system, enabling his units to operate independently on multiple road networks, while being able to concentrate in force for an engagement (because you simply can’t put tens of thousands of men on a single road and hope to move at anything more than a glacial pace). Railroads added new dimensions of scale and complexity, and the famous timetables for the German invasion of France in 1914 were marvels of planning and attention to detail. large scale amphibious operations took all of these moving pieces, and added the supreme difficulty of going from water to land, while being uniquely exposed and vulnerable to enemy fire. Clauswitz famously said that, in war, even the very simple things are difficult. In an amphibious operation, almost every type of Clauswitzian friction is magnified. Accounts of amphibious landings in the second world war always involve stories of men and machines fighting against wind, current, and surf just as much as against the enemy (the majority of tanks and howitzers deployed on Omaha beach sank before reaching shore).2 The June 6 landings themselves were a risky gamble, taking advantage of a brief window of marginally fair weather, which, owing to the confluence of moon and tides, wouldn’t repeat for another month.

Rick Atkinson’s Guns at Last Light gives a glimpse of the logistical planning required.3 “Seven thousand kinds of combat necessities had to reach the Norman beaches in the first four hours, from surgical scissors to bazooka rockets, followed by tens of thousands of tons in the days following.” Merchant marine captains arranged scale wooden blocks on ship blueprints “like chess pieces to ensure a fit,” and rehearsing soldiers maneuvered trucks and guns on full-sized replicas of ship decks. The litany of items needed for coordinating and preparing the invasion included 20,000 rail cars, 300,000 telephone poles, and a “calculated daily combat consumption, from fuel to bullets to chewing gum, at 41.298 pounds per soldier.” The invasion required 3,000 tons of maps, 280,000 hydrographic charts, and a million reconnaissance photos of German defenses. “The U.S. First Army battle plan for OVERLORD contained more words than Gone with the Wind. For the 1st Infantry Division alone, Field Order No. 35 had fifteen annexes and eighteen appendices.” Medically, D-Day required “8,000 doctors, 600,000 doses of penicillin, fifty tons of sulfa, and 800,000 pints of plasma meticulously segregated by black and white donors.” Whole blood donations were acquired to complement the plasma, but the blood was only viable for two weeks at a time. The blood, like the vomit-logged cargo holds of transport ships full of seasick men, could not be held in waiting indefinitely.

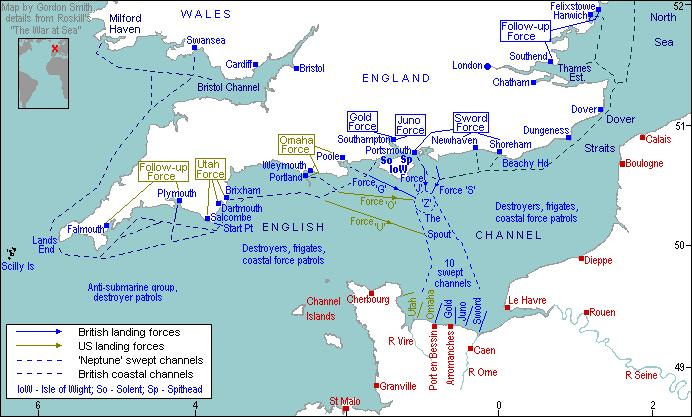

If the Schlieffen plan’s timetables in 1914 were a masterpiece of precision engineering, Overlord’s planning was an operatic ballet of moving parts that had to harmonize across multiple domains all at the same time. Allied troops had to travel and embark from 1108 locations scattered across Southern England and Wales, and link up with enough supplies and equipment to immediately sustain large-scale operations in France. While the initial landings involved around 150,000 men (not counting naval and air assets), the follow-on forces swelled to nearly a million men and over 175,000 vehicles during the first month of the invasion. Not only did these units need to land combat-ready, they had to be continually supplied in the field, but without permanent harbor facilities. The famous Mulberry artificial harbors were incredible feats of engineering unto themselves, requiring 1.5 million tons of steel and concrete. In the first week after D-Day, over 325,000 men and over 50,00 vehicles were put ashore.4 Even so, supply shortages persisted, as units ran low on ammunition. At one point, extra grenades were literally flown across the channel.5

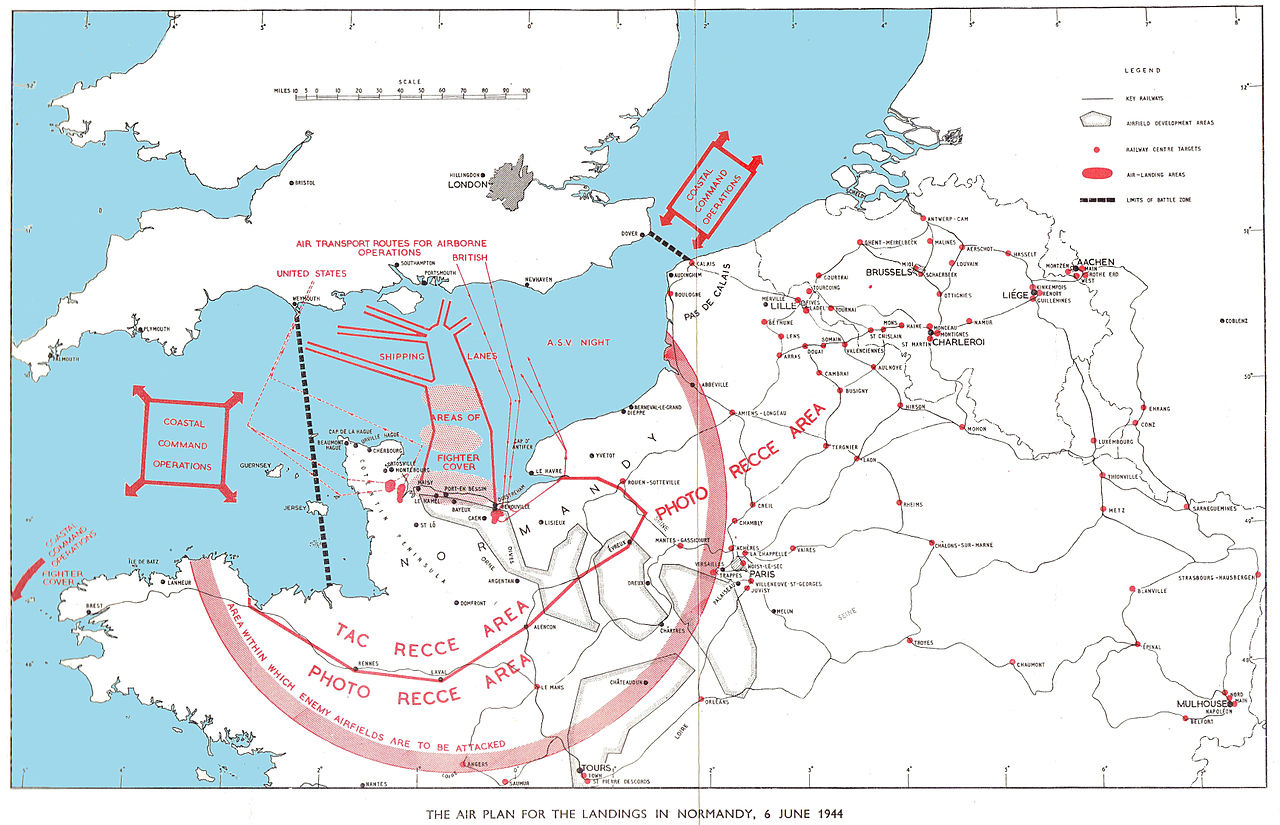

Few armies in history have been able to organize such a large and complex operation, and yet this only accounts for one operational domain, because the navy and air forces also had to synchronize their own enormous performances. In the air, almost 12,000 planes would fly over 15,000 sorties on D-Day, the British alone dropping 5,000 tons of bombs,6 while 171 separate squadrons of fighters covered pre-planned patrol zones.7 At sea, 2,700 ships (plus 1,900 landing craft) carried out a huge number of direct and ancillary support roles, from transportation, to shore bombardment, to minesweeping, to air defense, all requiring their own careful instructions, patrol areas, and contingency plans.8 British Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay’s operations orders, issued to both fleets (its terminology “translated” from Royal Navy usage to that of the United States Navy), contained twenty-two annexes and stretched to over 1,100 pages in length. Ramsay explained that, “this is probably the largest and most complicated operation ever undertaken and involves the movement of over 4,000 ships and craft of all types in the first three days. The Operation Orders are therefore necessarily voluminous.”9 And, before and above this entire armada, 1,200 aircraft carried over twenty-thousand airborne infantry, who parachuted and glided down in yet another complex ballet, with the fate of every paratrooper held by the promise of every other part of the armada doing its job.

If all this weren’t enough, orchestrating an invasion in the face of uncertain weather and a determined enemy also required the smooth cooperation of every major branch of the armed forces of multiple nations, which historically is almost as difficult a feat to manage as a large amphibious operation itself. Naval, air, and ground forces all belonged to separate institutions with their own traditions, cultures, and interests, and stories of friction and rivalry between the various branches dominant many of the famous battles of the second world war. Militaries cultivate morale and esprit de corps by fostering pride and a deliberate sense of separation from other groups, which can easily create suspicion and distrust between branches. One of the hallowed verities of the United States Marine Corps down to this day rests on the belief that the Marines were abandoned at Guadalcanal by the Navy, and Marine and Army units frequently chafed at being commanded by rival generals in the Pacific. Meanwhile, the prophets of strategic bombing had to be reluctantly persuaded to shift to tactical operations in preparation for Normandy. Soldiers griping about “navy pukes” and absent flyboys is a well-worn trope in literature and media of the war. Although the Normandy operations demonstrated many instances of heroism and sacrifice across services branches, there were tensions and competing institutional habits to overcome, all the way down to the fact that the Army and Navy somehow had different official numbers for the same LSTs. “A perplexed GI could board both LST 516 and LST 487, which were one and the same.”10

At the highest level, these points of friction were, if anything, magnified by national differences, as rival leaders (usually men with large egos and ambitious wills) competed for resources and jockeyed to have their visions for winning the war given priority. The British famously resisted American plans to invade France in 1943, opting instead for Churchill’s “soft underbelly of Europe” in the Mediterranean. This resistance only aroused the suspicion of anglophobic American generals that perfidious Albion was still conniving to protect its empire. In addition to planning and managing, one of Eisenhower’s greatest strengths was diplomacy and tact, although this often meant that he just received flak going both ways. Some American generals (not merely Patton) sniffed that Eisenhower was too pro-British, even while British critics such as Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke agitated for promoting Bernard Montgomery over Eisenhower. Late in 1944, Alan Brooke wrote in his diary that Eisenhower ought to be removed from supreme command, and subsequently tried to go over Eisenhower’s head to Army Chief George Marshall and “take the control out of Eisenhower’s hands.”11 While Patton is one of the most famous prima donna generals of the war, Montgomery was arguably an even bigger irritation for Eisenhower than Patton himself.

The legacy of these internecine disputes and the lessons learned from them remains extremely visible to this day, in the international structure of organizations such as NATO, and the American military's obsessive habit of insisting that everything must be a “joint” operation, platform, or weapons system. Arguably, one of the towering accomplishments of the allies during the second world war was the creation of the institutions and practices that make such cooperation seem so routine and effortless today.

“There are two kinds of people who are staying on this beach: those who are dead and those who are going to die. Now let’s get the hell out of here.”

- Col. George Taylor, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division

Despite this prodigious act of organization, planning, and diplomacy, success on D-Day still came down to tens thousands of wet and frightened men huddled in open-topped landing craft, standing in seawater, blood, and vomit. These men were flung ashore across three-hundred yards of obstacle-strewn, bullet-scoured sand, itself overlooked by bluffs and concrete walls topped with trenches, barbed-wire, and pillboxes. On Omaha, “one sergeant calculated that the beach was swept with ‘at least twenty thousand bullets and shells per minute.’”12 Not every beach was so lethal, and the final casualty count for D-Day (around 12,000 killed and wounded) ended up being less than planners had feared, but no one headed for a different beach could have known their luck ahead of time. 13

The operatic ballet of men and material planned out over months and months all culminated in those desperate moments of terror and bravery, where preparation and organization broke down under water and fire. Small groups of men cowering under the sea-wall found their leaders and their courage, and began to gut, shoot, grenade, and bangalore-torpedo their way through the beach defenses, backed up by destroyer captains sailing dangerously close to shore in order to provide point-blank fire support. They were also supported further inland by the efforts of the paratroopers. These men, sometimes scattered miles away from their drop zones, came down in fields, trees, swamps, and villages. They groped about in the dark for friends, often found strangers from other units, and then set about causing mayhem. One of the serendipities of such a carefully planned day was the chaos caused by scattered paratroopers who simply fought Germans wherever they found them, thereby sowing confusion as the Germans tried to discern a plan and order that wasn’t there.14

At the strategic level, the allies enjoyed on paper material advantages that appeared to be almost insurmountable. It’s easy to write an economic determinist narrative of the second world war, especially when you throw in Germany’s systemic problems with organization and corruption. Samuel Eliot Morrison, in his official history of the US Navy during the war, described the buildup and preparation for the invasion as “Coiling the Spring,” which works wonderfully well to describe the winding up of such vast amounts of potential energy.15 D-Day was the product of years of directed human agency and astonishing amounts of labor; probably the greatest display of state capacity and rational action the world has ever seen. Yet that enormous effort of logos had to be condensed and narrowed into one tight focal point barely fifty miles wide. In that moment of action, all the reason and planning in the world had to be carried ashore by courage.

From that moment flowed the liberation of Europe, and our memories eighty years on.

Most of these lessons involved planning and coordinating large forces across the multiple domains of land, sea and air, and finding a way to overcome interservice rivalries. Some lessons were as basic as learning to manage wind and tide, along with the importance of “combat loading” transport ships with food, water, and ammunition last, so that they could be unloaded first.

Paul Kennedy, Engineers of Victory, (NY, Random House, 2013), 272.

All citations in this paragraph are from Rick Atkinson’s Guns at Last Light (NY, Henry Holt, 2013), 23-25.

Kennedy, Engineers of Victory, 276.

Atkinson, Guns at Last Light, 116.

Alexander and Malcolm Swanston, The Historical Atlas of World War II (NY, Chartwell, 2008), 272-273.

Kennedy, 264.

Kennedy, 250.

Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol XI, The Invasion of France and Germany, (Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1988), 32.

Atkinson, 30.

Atkinson, 387, 406.

Atkinson, 69.

Atkinson, 85.

Atkinson, 50.

Morrison, 50-76.