The Historical Disposition and becoming a Dispassionate Observer

Part 5 on the nature of history and why we should study it

Roadmap update: with the looming start of the school year, I’ll have less time for writing, which is why partly I’ve front-loaded this more philosophical series of musings on history over the past month. During the school year, I aim to alternate each week between genuinely new essays, and posting updated/revised short chapters of class narratives I’ve written over the years. The current series is on the early Roman Empire, and the first few posts are already up (Pt 1, Pt 2, and Pt 3). Part of the purpose of this blog is to help me regularly update and improve much of my existing content and handouts. As it grows, I hope it can be a resource for others, especially classical school teachers and homeschooling families.

So far, we’ve discussed the need for treating history as inquiry into past thoughts, and how interpretation lets us map the past as a prudential guide towards the future. Next, I want to consider some features of the mindset that historical inquiry requires. Let’s look at objectivity, the problems of bias, and how to cultivate the skill of dispassionate interpretation.

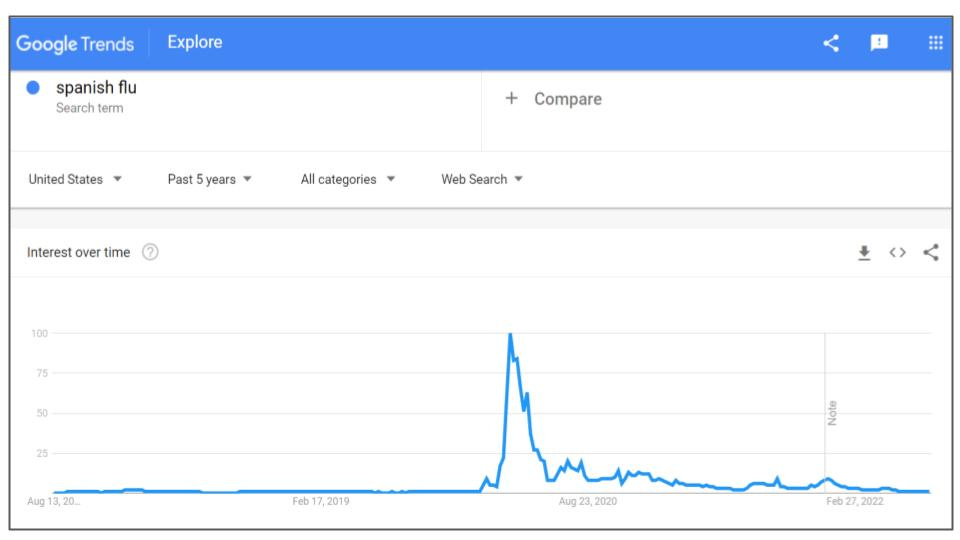

There’s something of a paradox at play in the fact that historical inquiry requires as much objectivity as possible in order to accurately re-enact past thoughts, while at the same time it is almost always present concerns that drive our desire to question the past. Different time periods take on new meaning and importance as present circumstances shift. The history of the Kievan Rus and the formation of Ukraine suddenly became a much livelier topic of interest in my classes this past Spring than in previous years. Likewise, Middle Eastern and Islamic history seemed a whole lot more important to Americans on September 12th, 2001, than it had two days earlier.

So, some present concern usually prompts us to say “why is this?” Yet, the answer to our question requires setting aside most of the emotional pull of those concerns, and trying to view the past as dispassionately and objectively as possible. We may feel invested in the answer, but, like a doctor diagnosing a patient, our concerns are ultimately best served by the truth. A physician who tries too hard to ignore possible cancer symptoms, or who sets out to prove another doctor wrong with their own pet theory of the case, isn’t acting in the best interests of the patient. So too for the historian. Dispassionate interpretation, however, does not mean the implications of that interpretation must be bloodless and cold. The past can and should arouse excitement and wonder, but the joy must come after the careful inquiry.

The historian has a moral obligation to strive for accuracy, even if perfect objectivity is impossible. We necessarily view the world from one existing perspective, made up of countless influences and assumptions, which are always going to color out thoughts and actions. When done right, we can harness our perspective and prior assumptions as an aid to insight and interpretation; we are not Kantian minds viewing reality as an abstraction. But the very possibility of historical interpretation assumes that we can actually know something outside of ourselves; to re-enact the past means to set aside part of our minds and enter (as imperfectly as possible) into the mind of someone else and draw a conclusion. If objectivity is utterly impossible, then so is all historical knowledge.

The unattainability of perfection is no excuse for a sculptor seeking to capture the human form, or for a physicist trying to account for every possible variable in an experiment. Given how much wonder and awe art and science can generate in their imperfection, the historian has no excuse not to try, even if failing in the attempt. The charge was laid down two millennia ago by Thucydides:

“And with reference to the narrative of events…it rests partly on what I saw myself, partly on what others saw for me, the accuracy of the report being always tried by the most severe and detailed tests possible. My conclusions have cost me some labour from the want of coincidence between accounts of the same occurrences by different eye-witnesses, arising sometimes from imperfect memory, sometimes from undue partiality for one side or the other. The absence of romance in my history will, I fear, detract somewhat from its interest; but if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the interpretation of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble if it does not reflect it, I shall be content.” - Bk. 1.22

How bias occurs -

There are two main ways in which the historian can fail in their quest for objectivity. The first is when present concerns drive the interpretative outcome, whether it be pet theories we seek to uphold, or emotional attachments to a chosen side or position. If a historical claim acts as load-bearing evidence to a body of theory, then there can be powerful incentives against disproving the claim. The second is the failure of imagination that happens when we don’t accurately re-enact past thoughts, either for lack of evidence, or because our own prior assumptions blind us to the ways in which people in the past acted and thought differently from us.

We can group most types of bias together, whether it be political, cultural, national, or just personal. Was the New Deal good, or bad for America? How great (or not) a president was Ronald Reagan? Was the Protestant Reformation a heroic act of idealism, or was it manipulated and hijacked by political interests? Just how oppressive were the British towards colonial Ireland? Has America always been exceptionally great and unique? Take most any political partisan today, and you can probably predict their views on a range of historical topics. The same often goes for devout members of a particular religion, and ardent nationalists. A college roommate of mine once mentioned that he frequently saw the content of the Wikipedia entry for the Armenian Genocide go back and forth as Turkish and Armenian editors got hold of the article (this was back in the early days of Wikipedia). Perhaps more innocently, but no less passionately, online “nerd” debates over military history are well-known for their devout acolytes who extol the virtues of favorite nations and weapon systems.

In most cases, errors stem from seeing too much of what we want to see, and discounting what we don’t want to see (this is another riff on the “historical cherry-picking” and motivated-reasoning problems we talked about in the very first post in this series). Sometimes, bias is a simple matter of having a strong attachment for or against a person, event, or “side,” and just running with it too far. If we’re trying to win an argument in the present, or support a position we have a strong attachment to, we risk only consulting the historical evidence as a prop for that position. It’s hard to deliberately look for information that might prove us wrong or complicate our chosen narrative, and our scientific and legal professions invest very heavily in complicated systems and processes to try to help counter and balance out this understandable temptation. The historian has to try to cultivate this disposition for themselves.

Beware monocausal explanations -

Whenever someone says a historical event or controversy was “really all just about this one thing…” whatever follows next is almost sure to be an error or over-simplification (including this statement). There’s often a temptation to make one neat explanation fit for an entire phenomena. But history is (usually) complicated, and most events and figures will have a number of interdependent variables at play.

This is not to say that some interpretations aren’t better than others, or that one “side” may have a better claim to the history than another; at the end of the day, I too have my own beliefs and positions that I think are supported by the history. I think it’s fair to say that slavery was the central variable at play in the American Civil War, but if you say it was “only” about slavery, and ignore all the other variables (cultural differences between North and South, industrial policy, the distribution of tax revenues, etc), you’re weakening your position rather than strengthening it.

If you get to know someone very closely, you’re sure to find them a complicated individual with many motivations (often even contradictory ones). Your parents, spouse, or best friend probably can’t be summed up in a sentence or two. You may find, however, that you have set narratives for people you know less well, or that other individuals have simplistic narratives they map onto you. If you write off someone’s disposition as “oh, everyone from the North is like that,” or “they’re just like that because of their mother,” you are most likely not treating that person fairly. Watch out for these habits; they can become subconscious explanations for things. These same patterns map remarkably well onto our interpretations of history.

More innocently, sometimes, we unthinkingly create a monocausal explanation because we simply don’t know very much about a topic. If we only have one piece of evidence for a thing, then that thing can become the narrative itself. Upper-level high school students, and underclass college students are often prone to this, as with the stereotypical college freshman who comes home from their first semester acting like a know-it-all. It can be exhilarating to feel that something important has been figured out; and the mental act of thinking a problem is “solved” can cause you to stop inquiring; after all, you know the answer now. Teachers should take great care not to give students the impression that a difficult topic can be breezily explained away with a quip; especially an ironic or derogatory one.

Other times, monocausal explanations take hold and become popular simply because they have virality. A historian writes a five-hundred page book based on years of research, complete with plenty of nuanced caveats and qualifications. The book then becomes the basis for a ten-minute condensed narrative by an enthusiast podcaster or blogger, which then becomes a two-minute explanation passed along at the dinner table by the average reader or listener. My own profession of teaching is guilty of this all the time; we teachers are generalists who have to rapidly condense book-length arguments (which we often don’t have time to read slowly and carefully) for students, who will often take away garbled versions of the concept. Something similar happens with political proposals and agendas, where dense academic position-papers become catchy sound-bites repeated endlessly in stump-speeches by politicians.

Often, there’s nothing nefarious here, just the normal process of knowledge dissemination, as we can’t all be specialists. But it’s worth remembering that, whenever you encounter an argument or interpretation, you’re probably hearing a very distilled version of a thought-process that started out as something much more complex, and which was probably carefully constructed to answer a specific question that might be different from the way it’s being popularly used.

Cultivating a disposition for historical inquiry -

Some bias is inevitable, and interpreting the past is just plain difficult to begin with. We’re all walking around with sincere, well-thought out, and deeply held beliefs that just so happen to be dead wrong (as such, it’s worth treating others with whom we disagree with as much charity as possible). If we knew what those wrong beliefs were, we’d almost certainly change them.

Here are a few suggestions for cultivating a more dispassionate approach to interpreting evidence. These have a lot of crossover with general habits of argument, debate, even interpersonal disputes. After all, re-enacting past thoughts is simply another form of conversing with someone who thinks differently than you:

Try to have a “Scout mindset” as opposed to a “soldier mindset.” Soldiers (in this metaphor) feel the need to dig in and defend something by defeating an opponent. But scouts do their job best by trying to observe as accurately as possible. A scout might not want there to be a huge enemy force on the other side of the hill, but they endanger their side even more by engaging in wishful thinking.

“Steelman'' the opposing side of an argument or position (as opposed to strawmanning) by trying to find and engage with the other side’s strongest claims. If you’re really convinced that Japanese Samurai warriors were the best swordsmen in history, then seek out the strongest opposing arguments and take them seriously. If you’re still convinced afterwards, then you can be even more confident in your belief.

Be skeptical whenever a narrative feels too good to be true. If at first glance something really seems to line up well in support of your chosen conclusion, be suspicious of it. Historical events happened in very different contexts from our own. What’s more likely; that you’re reading into the evidence what you want to see, or that a historical event independent of you just happened to exemplify the importance of your preferred outcome?

There are few heroes in history. If you’re an adult reading this (or perhaps a teenager), you can probably remember whenever you first experienced the letdown of realizing that someone you really admired wasn’t perfect. The same goes for historical individuals, organizations, and even civilizations. The lives and achievements of powerful kings and famous inventors are almost universally colored with occasional failures, personal faults, and mixed legacies. Most of the people you know best are not one-sided heroes or villains, and the same goes for historical figures.

Make “skin in the game” work for you rather than against you, by creating incentive structures that push you towards objectivity rather than away from it. As odd as this sounds, you can actually learn a lot about bias from sports. Devout fans are often homers for their own team, inflating the greatness and dismissing the weaknesses of their favorite players, and creating wildly. But take twelve rabid fans, and have them play in a fantasy league with real money on the line, and they’ll immediately become more objective about rating and evaluating the players they draft for their team.

One way to make “skin-in-the-game” work for you is to act as if your “side” is the historical record itself. It’s fine (and good!) to have political, cultural, and religious attachments. But history happened for its own reasons, and not in service of the present. History doesn’t care about your preferred tax policy, and partisans who weaponize history for their own motives often have incentives to ignore difficult evidence. But if you cultivate an attachment to history as “no, this really happened, and figuring out how and why takes precedence” then in the long run, you’ll actually become a better advocate for whatever you believe in.