Papal Rivalries and the Separation of Church and State - Pt Two

From Investiture to the Wars of Religion, and the Renaissance Papacy

This is the second installment in a series on the history of the papacy and its rivals. Part one may be found here. Much thanks to everyone who read and shared part one, making it the highest viewed post on this blog to date.

Pope and Crown

Part one of this series concluded with a look at the “Rule of Harlots” period, and the Papacy’s successful efforts to reform and strengthen the church. Once again, however, one set of institutional developments led to a new set of conflicts, in this case, the Investiture Controversy. The Gregorian Reformers needed to build up the prestige and authority of the Papacy in order to carry out their moral and clerical reforms, and in doing so, they collided with the growing power and nascent state-building projects of Europe monarchs.

Despite rhetoric from papal pronouncements at the time, and later histories from both sides of the Reformation, the power and ability to appoint bishops during the High Middle Ages was a constant back-and-forth series of negotiations and power struggles between crown and papacy, without any permanent solution. In practice, influence over church governance could vary a great deal, depending on the relative prestige and personalities of popes and kings and their political strength. Unlike today, where modern international institutions can coordinate and influence their members even at a granular level across great distances, medieval infrastructure and painstakingly slow communication meant that knowing the quality and character of individual bishops and their dioceses could be very difficult. The papacy of the modern Roman Catholic church actually exerts a great deal more direct influence upon its various organs, thanks to instant digital communication.

Further complicating and raising the stakes of medieval church politics, was the fact that Bishops were often feudal lords themselves. In many cities, Bishops had simply taken over/continued the civic administrative duties of patrician elites in the late Roman Empire. Throughout the middle ages, Bishops often served as key feudal lords controlling territory and wealth that was vital to monarchs. This rationale for political bishops is perhaps not always obvious to modern audiences. If one has a strong preference for religion, then it’s natural to wish for bishops to be appointed and managed by the church. But perhaps paradoxically, secular leaders are probably equally likely to conclude that separation of church is a good thing, and that religion should be walled off from politics as much as possible. But in the Middle Ages, the power, authority, and prestige of the Church as an institution made it inherently political, even before considering how many bishops were also explicit feudal lords (consider the fact that the Church had to take active steps to ban clerics from fighting in combat; in the Song of Roland, Archbishop Turpin runs his lance through his own fair share of Saracens after blessing the Frankish army and commending them to God). Imagine our reaction today if a foreign political power could appoint mayors of key cities in America, and you have a bit more of an idea how Bishoprics and important Abbeys sat awkwardly across religious and political lines.

Prior to the Gregorian Reform movement and the rise of the “Imperial Papacy,” the power to explicitly appoint and install bishops was not a special papal prerogative. It was something of an innovation, in an attempt to assert more control over the church, that the Papacy began to advance this claim during the High Middle Ages (though one could trace a through-line running back to Pope Gregory the Great turning the Papacy into a managerial head with broad influence). In 1077, Pope Gregory VII and King Henry IV of Germany famously clashed over Investiture; literally, the question of who should invest bishops with their symbols of office, meaning, their clothes and tools. In a papal pronouncement known as The Dictates of the Pope, Gregory VII asserted that he could make or unmake any bishop he wanted, as well as any king, that no bishop or king could correct him, and that he could not err. In response, Henry IV wrote an incendiary letter, refusing to address Gregory by his papal title, and ending with a thundering, “I Henry, king by the grace of God, do say unto thee, together with all our bishops: Descend, descend, to be damned throughout the ages.” Naturally, Gregory VII excommunicated the King.

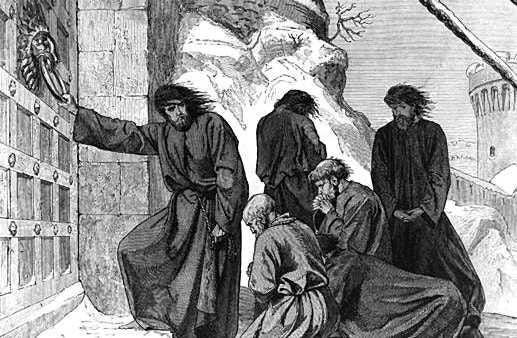

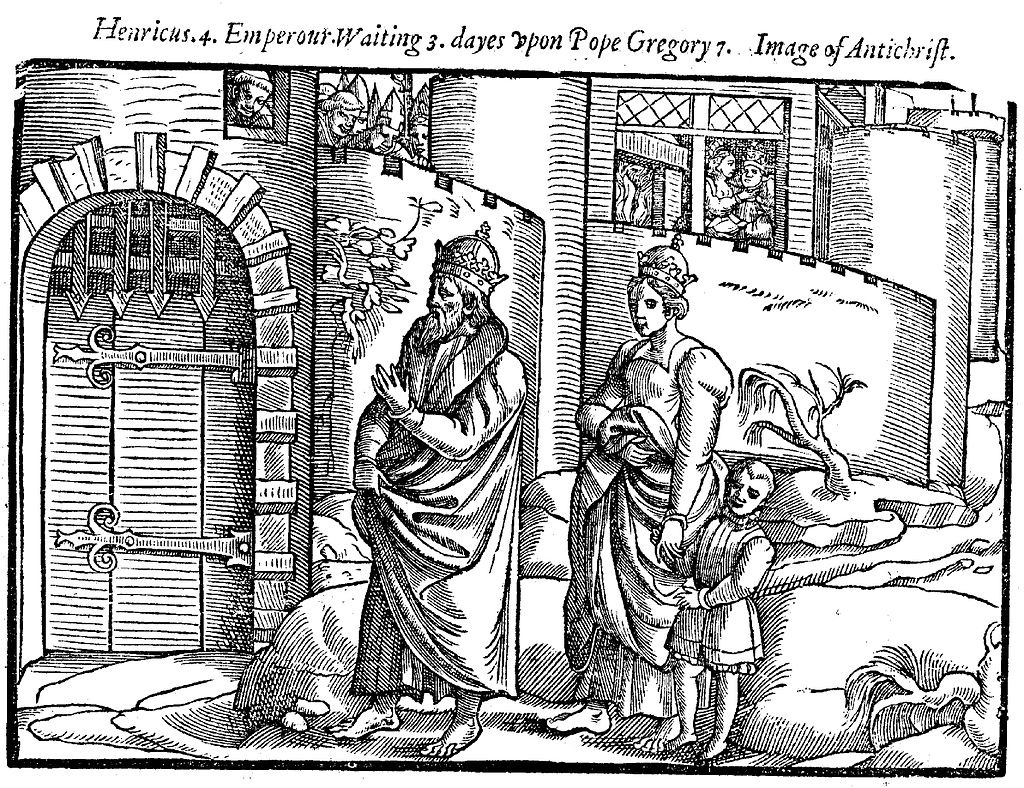

Joseph Stalin may have derisively (or apochryphally) quipped “how many divisions does the Pope have?” But in the Middle Ages, the answer to Stalin’s question was, “every feudal vassal who wants to be released from his oath.” Henry VI immediately faced a civil war and baronial revolt which he could finally end only by knuckling under and grovelling. In January of 1077, Henry trudged through the snow on foot as a penitent, to a Papal fortress at Canossa, in Northern Italy. Gregory kept Henry waiting outside in the cold for three days just to prove the point, before condescending to admit the Emperor, and graciously bestow forgiveness and absolution on the King, who knew his lines and how to swallow his pride. This triumph of Papal power was reproduced in church art over and over again through the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Less well remembered, however, was the fact that a few years later, Henry invaded Italy and chased Gregory out of Rome. Gregory would die in exile in Southern Italy, with his epitaph recording, “I have loved justice and hated iniquity; therefore, I die in exile.”

While the Concordat of Worms in 1122 would hash out an uneasy compromise on Investiture, theoretically splitting the official duties and powers of a Bishop and bestowing his political accoutrements on behalf of the crown (literally, giving the Bishop his lance as a knight) and his spiritual garments on behalf of the Church, investiture wasn’t truly solved. For the rest of the Middle Ages, Crown and Papacy would see-saw back and forth in a power struggle for control of local bishoprics that varied much according to geographic distance, and the burgeoning state-capacity of each kingdom in Europe. Just as Constantinople remains today somewhat underappreciated as a Papal rival in the Early Middle Ages, the rivalry between the Papacy and burgeoning state-capacity and political centralization in the Late Middle Ages is also somewhat overlooked by popular historical audiences, even ones who might readily remember the Avignon Papacy and Great Schism of the 14th century. Nonetheless, this rivalry is well attested in mainstream historical scholarship, and all the pieces are clearly there once you shift focus a bit and look for them.

Pope and State

In 1303, Agents of King Phillip IV “The Fair” (recently excommunicated after attempting to impose taxes upon the French clergy) kidnapped Pope Boniface the VIII, and held him prisoner for three days. Boniface would die a month later, reportedly of shock from the experience. At the ensuing Papal Conclave, King Phillip pushed through Clement V as his candidate, who then relocated the Papal See to Avignon (in modern France), where it would remain from 1307 to 1376, memorably deplored by Petrarch as “the Babylon of the West.” Although the Western Papal Schism, which at one point featured three popes/antipopes at the same time, was eventually resolved in 1417 (helped by the Council of Constance, and, according to church tradition, by the visions of St. Catherine of Siena), the French crown, rapidly centralizing and gaining muscle in response to the Hundred Years War with England and traditional independence of the French nobility, continued to exert a great deal of direct influence over the Church in France. In fact, this influence eventually gave rise to the entire notion of a “Gallican Church,” whose adherents claimed was uniquely independent within Christendom, and tied to the French monarchy. This is partly why 17th century Cardinals such as Richelieu could famously rationalize their foreign policy with their piety, and why during the Revolution, the Jacobins saw the French Church establishment (the “first estate”) as simply another organ of the ancien regime. In Revolutionary France, throne and altar went to the guillotine together

Or take Spain, where everyone knows to expect the Spanish Inquisition in histories of the early modern period. However, those who know just a bit more than the infamous (and exaggerated) Black Legend know that the reason the Spanish Inquisition had so much power and terror was because the Crown had direct control over it, and wielded it as an explicit arm of the state. The broader history of the medieval church inquisition as a court system is far less bloody, which often took pains to protect and rescue innocent individuals targeted by mobs and false accusations.

In fact, outside of Italy (more of which below), Papal influence was strongest in Germany, where the Church was a huge landowner, and able to levy taxes and indulgences on behalf of building the new Cathedral of St. Peter’s in Rome.1 Centralized state-capacity was much weaker in the loose constitutional monarchy that was the Holy Roman Empire, and there the Reformation began; not where the Church was weak, but where it was strong. Also, even though state formation in England had been outpacing much of the rest of Europe, royal power there had weakened considerably during the Wars of the Roses, and the Tudor monarchy was still trying to rebuild it. Along with his personal megalomania, preventing another dynastic civil-war was another powerful motive shaping the reign of Henry VIII.

This lingering underappreciation for the rivalry between Pope and early modern monarchs most likely stems from the understandable fact that the Reformation still dominates our framing of the Papacy during this period. Ironically, however, both Catholic and Protestant narratives have had a vested interest in magnifying the power and political alignment of Rome during the Late Middle Ages. Catholic and Protestant histories alike naturally portrayed the Medieval Papacy as the linchpin of a united medieval political-religious order, which was alternatively good (for Catholics) or bad (for Protestants). Both sides could therefore portray the Reformation as shattering something. Even Enlightenment and 19th century Nationalist histories were happy to perpetuate this narrative, since doing so allowed them to pull-forward the political development of secular politics and the nation-state as new (good) creations; like Pontius Pilate, able to wash their hands of the chaos and tumult of the Wars of Religion.

In reality, the Imperial Papacy of the 12th and 13th centuries was a temporary high-water mark, and not a perpetual norm, and Papal power was already being challenged by rising early modern states, even before the Reformation. This dynamic also explains how political and dynastic rivalries constantly frustrated attempts to unify Catholic Europe in opposition to Protestantism. For all that Bourbon France, and Habsburg Spain and Austria were co-religionists and nominally aligned with the Pope, internal dynastic concerns and raw geopolitics fractured and realigned the European balance of power, to the point that the 30 Years War was much less of a religious war than its combatants claimed. If you’re familiar with this period, you probably know that Cardinal Richelieu first subsidized Lutheran Sweden in Germany against Catholic Austria, and then overtly committed France into opposing Spain in an attempt to break “the Habsburg Ring.” But histories of the 30 Years War show how frequently Habsburg Austria defined its own dynastic fortunes as synonymous with Catholic Christendom, to the continual frustration of the Papacy.2 Older Protestant histories were less interested in differentiating amongst such an array of religious enemies, but Papal power and influence was already being scraped against and crowded out by the concerns of the various “Catholic Majesties of Europe.”

The Renaissance Papacy

But what about Italy, so close to the Papacy itself?

In early modern Italy, the prestige, influence, and power of the church hierarchy itself couldn’t help but make it one of the most important political levers in all of European politics. While in Spain and France the church was too important an institution not to bend to the will of the emerging state, in much of Italy, the church hierarchy was simply another expression of political power, thereby all but erasing the distinction between spiritual and temporal. With no central monarchy, power in Italy was fragmented among many powerful city-states and foreign agendas. Bishops and cardinals wielded huge influence and resources, both as explicit political power (most notably the Papal States itself), but also often at cross-angle purposes to every other social and political entity in Europe. It’s not an accident that in chess, Bishops move along the diagonal.

On top of this potent fusion of political and spiritual authority, Italy was also one of the richest and most densely urbanized regions on the planet, with many different polities and duchies pressed together in a highly competitive and unstable environment. With no overarching hegemonic power or cultural divisions, and few geographic barriers amongst closely-packed rivals, coalitions and alliances shifted constantly. To make matters worse, Italy’s wealth, influence, and fragmentation made it a ripe target for every other major power in Europe to meddle in. The Italian Wars of the 15th/16th century spurred dramatic innovations in military organization, technology, and siegecraft. The famous star-shaped geometric fortifications that came to define urban defensive architecture during this period are known as the Trace-Italianne. When the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II planned the final conquest of Constantinople, he read Italian manuals on siege warfare.

To give one brief example of the complexity and instability of this game-state, the War of the League of Cambrai lasted from 1508 to 1516, and featured at various points most of the major powers of Europe. The war started with an anti-Venetian alliance led by the Papacy, only for the French and Pope Julius to fall out. The Papacy switched sides and joined the Venetians in expeling the French from Italy, only for the Venetians to finally ally with the French, and eventually return most of Northern Italy to the pre-war status quo.

Political philosophical theory often credits (or blames) Machiavelli for “inventing” realpolitik and ends-justifies-the-means utilitarianism, but it’s arguably better to think of Machiavelli as simply trying to make sense of and understand an incredibly high-stakes and cutthroat world that already existed. And as the ultimate expression of spiritual authority in a world where religion undergird every aspect of reality, the Papacy sat right in the center of this pressure-cooker.

It’s no wonder then, that the worldliness, ambition, and art of the Renaissance Papacy is so (in)famous. Every major kingdom and influential political family in Europe was willing to go to almost any lengths to control key positions in the church hierarchy; keeping loyal allies and family members in, and rivals out. Any political state which didn’t attempt to play the game, would be defeated, creating a classic prisoners-dilemma situation, where no one could afford not to burn down the spiritual integrity of the church by attempting to bend it to their own ends.

In 1489, Lorenzo the Magnificent of Florence maneuvered to have his 13 year-old son Giovanni given a Cardinal’s hat. In 1513, after the death of Pope Julius II, Giovanni successfully won over the college of Cardinals and was elected as Pope Leo X. On his election, Leo supposedly remarked, “God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it.” Leo enjoyed hunting and patronizing art, but he also joined the winning side in the War of Urbino, successfully installing a family member as Duke, and he took steps to reform the college of Cardinals after surviving a plot from some of its members to poison him. Leo also attempted to raise a Crusade against the Ottomans. It’s probably easy to see why he was totally unprepared for the outbreak of the Protestant Reformation, initially dismissing Martin Luther as some “drunken monk” who would get over the whole business of indulgences after sobering up. But even Leo X’s career pales in comparison to that of the Borgia family (Alexander VI and his son Cesare) in the 1490s, and then Pope Julius II (1503-1513).

Ada Palmer is a Renaissance scholar at the University of Chicago, who has an excellent deep-dive series on the career and writings of Machiavelli. Her description of the Papal Conclave of 1492, which elected Rodrigo Borgia as Pope Alexander VI, is worth quoting at length:

“The papal election of 1492 was one of the great power games of world history. Anyone seeking to create a board game or one-shot role-playing simulation of an exciting political moment need look no farther. Twenty-three men are locked in the not-yet-Michelangelized Sistine Chapel. They can’t leave until someone receives twelve votes and becomes pope. Everyone has a different goal. A few want to be pope. Others want to sell their votes to the papabile (pope-able candidates) for the best price going. Some want wealth; some have plenty and want to turn it into power. Some want titles; some have titles but have lost the fortunes that should go with them and are hoping to earn that back. Some are young and want to make friends and be owed favors; some are old and want young relatives to become cardinals to preserve the family’s toehold in the College. The Medici Cardinal is sixteen and hoping to cement the family’s hold on Florence. The Patriarch of Venice is ninety-six, dying, and wants to go back to his impregnable hometown and eat candy. Ten of the cardinals present are nephews of previous popes, eager to keep nursing from the coffers and to keep their family fortunes safe from rivals. Eight are pawns of kings and want to secure the clout necessary to get the new pope to grant their masters’ requests should a king want to, for example, divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boelyn (that’s a few decades off but it’s the kind of thing one has to be prepared for). The previous pope glutted the College with his own relatives but all are too young for anyone to be willing to vote for them, so they have thrown their collective clout behind the cunning veteran Giuliano della Rovere: learned, aggressive, interested in art, interested in the classics, and interested above all in how both can be used as tools of power. As for Rodrigo Borgia, he has waited a long time. This may well be his last shot at his uncle’s throne. Resources: all the wealth, contacts, secrets, tax-returns and dirt he has accumulated in decades managing the papal purse.

It was a very complex election, about which we have lots of information, but little that is reliable. We know there were four rounds of voting, and that Borgia was not one of the front runners in the three leading to his unanimous or near-unanimous victory in the last. We have records of enormous bribes, offices and territories representing tens of thousands of florins in annual income changing hands. Some allege that the king of France contributed hundreds of thousands to efforts to get Giuliano della Rovere on the papal throne. It seems pretty clear that the Borgias smuggled letters offering fat bribes into the chapel inside the food which was delivered for the cardinal’s meals. One delightful anecdote from the period claims that the 96-year-old Patriarch of Venice was the last critical swing vote, who, having a wealthy family, secure lines of power, a literally impregnable homeland, and not long to live to enjoy the fruits of bribery, sold out for a couple hundred florins and some marzipan, since, when one is locked in the Sistine Chapel with a bunch of clerics for day after day, sweets are precious hard to come by.”

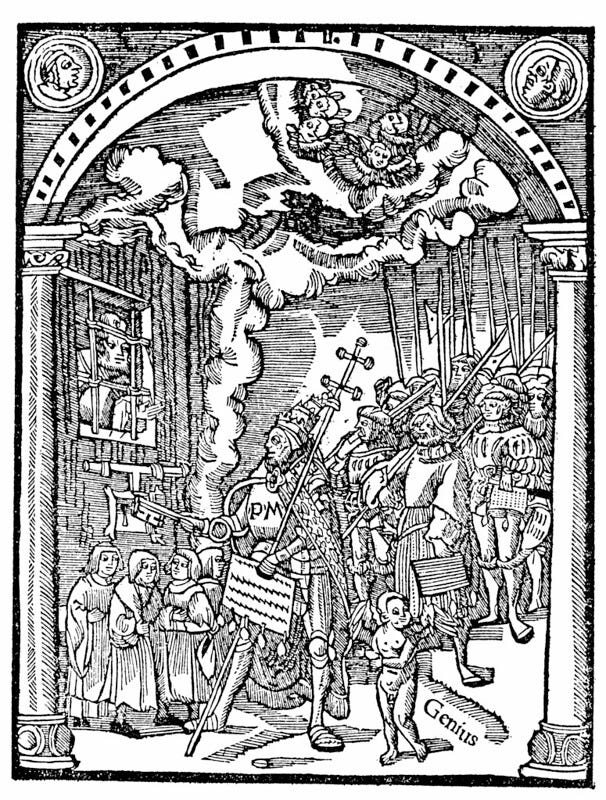

Giuliano della Rovere would bide his time during the reign of Alexander VI, and then outmaneuver the French power-bloc in 1503 winning election for himself as Julius II. As Pope, Julius II immediately backstabbed and arranged the downfall of Cesare Borgia. He then waged multiple wars in central Italy, developing a reputation as a skilled artillerist, and would famously quarrel with Michelangelo over the Sistine Chapel, becoming one of the great artistic patrons of the Renaissance. After Julius’ death in 1513, the famous Dutch Humanist Erasmus wrote a scathing, and very funny, satirical account of Julius arguing at the gates of heaven with St. Peter himself. Ultimately, after refusing to listen to Peter’s repeated attempts to explain his sins to him, Julius leaves, vowing to return with his army (to which, in real life, he had promised salvation for fighting on his behalf) and storm the gates of heaven itself.

Such was the Renaissance papacy. If you want the full details on the Borgias including all the murders and intrigue, there are outrageous TV shows and lurid descriptions in plenty to be found. Ada Palmer’s account of Cesare Borgia’s career is an extremely useful companion to Machiavelli’s Prince. Personally, I don’t think Machiavelli can be really understood without first grounding his life in this incredibly violent and competitive world.

Understandably, we tend to find these papal power struggles shocking, corrupt, and hypocritical. We live in a world where the sincere idealism of humanists such as Erasmus and Thomas More have won out in judgement over worldly ambition and political rivalry within religious institutions. Certainly, the story of the Reformation can’t be told without first explaining the Renaissance Papacy, and the failed attempts of Catholic Christendom during the Wars of Religion to turn back the clock and stop the growth of Protestantism also can’t be told without growth of secular states, and the competing ambitions of rival monarchs. The Roman Catholic Church that emerged after the Council of Trent, and into the modern world, would be politically weaker, but stronger internally, and possessing higher standards of moral reform. In part three of this series, I want to tie all of these themes together, and look at how the Papacy and its rivalries helped create our modern separation of church and state, which is no small reason why the current Papal Conclave today is not going to elect anyone remotely similar to Alexander VI or Julius II.

In closing, I want to take a hard look at a question that we often tend to dodge when thinking about religion and moral idealism in the pre-modern world. Because we do live in a world where religious and political authority are divided, we have a hard time getting our heads around the pre-modern world, where the two were joined much closer together. Powerful figures bending religion to their will, and using it to advance their own ends, often seem to us merely corrupt or cynical, and we might even want to assume that such individuals simply didn’t believe in the religious ideals they were exploiting. As I touched on earlier, this is an explanation that, paradoxically, both religious and secular audiences today might actually both prefer. To a religious reader, such behavior is an enormous betrayal of the moral tenets of the faith, and perhaps more easily explained by the same extreme cynicism and false belief which a secular reader might also assume as the default.

But I think such simple explanations of cynicism and false belief, or secular frames of pure power-politics and material interests, are not sufficient, and that they fail to fully take the past seriously on its own terms. Because the ultimate reason the premodern church was so powerful, and so worth hijacking for political ends, was because everyone first believed in it. Belief in God, an afterlife, and a transcendent moral order, weren’t contestable propositions, but absolute certainties, and the power of the Papacy ultimately rested on the belief of millions that the keys of St. Peter were real.

Here’s the eminent medieval historian Chris Wickham on how to think about morality, power, and religion in the middle ages:

“I am stressing this, not because the point is contested by anyone, but because some of its implications are not always followed through. Secular and religious motives are often separated out by historians, and put into potential, sometimes actual, opposition. When aristocrats founded monasteries or gave them large donations land,putting their family members into them as abbots or abbesses, were they doing it for the religious motive which their charters of gift invoke (treasures on earth being exchanged for treasures in heaven, etc.), or were they doing it because such monasteries could remain controlled by their families and be a long-term landed resource, as families became too large and divided? When kings put their own chaplains and other administrators into bishoprics, were they doing so because they already knew how good these men would be as properly moral bishops, or were they trying to shore up royal authority in different parts of their kingdoms by putting reliable and loyal men into rich local power-bases? When the Frankish emperor Louis the Pious’ sons forced him to do public penance in 833 (see Chapter 4), did they do so because a substantial sector of the Franksih political class had decided that his sins had become so great that they threatened the moral order of the empire, or was it because his sons wanted to neutralise him so completely that he would have to abandon his political power to them on a permanent basis? When crusaders took the cross and went off to conquer Palestine in 1096 (see Chapter 6), did they do so because they wanted, as armed pilgrims with deep commitment, to take back the holy sites in and around Jerusalem from Muslim infidels, or were they wrapping up a well-attested desire to take other people’s land with a new set of religious justifications? When we face these questions, we have to answer yes to both sides in nearly every case; but, more important, we also have to realise that there were no two sides: the two motivations were inextricable, and would not have been regarded as separable in people’s minds. Of course, some political actors were more unscrupulous than others, just as some were more religious-minded than others; but neither of these would have regarded what we often see as two motivations as separate either, except in the case of a few religious hardliners. The self-servingness of much medieval religious rhetoric, particularly when it was the work of the powerful, can often be only too obvious to us; but it was not hypocritical. It might, sometimes, be more palatable (to us) if it had been; but such people, in almost every case, really did believe what they were saying. We have to factor that real belief into every assessment of medieval political action, however carefully and cunningly targeted.” (Chris Wickham, Medieval Europe, 20-210)

We might prefer to separate out moral actions and place them into neat, and easily understandable categories. Good popes and bishops were humble and self-effacing; ambitious and power-hungry were corrupt, and didn’t take their claims seriously. But, firstly, this is easier to do today, when we have drawn clearer lines separating transcendent and temporal realms and spheres of influence; the dividing line across them is sharper and clearer. Secondly, and perhaps even more importantly, avoiding this neat juxtaposition helps us pay the compliment of taking actors in the past sincerely, especially when it means accepting their own complexity and internal contradictions.

After all, we ourselves are very often home to internal contradictions and motivated reasons, convincing ourselves in all sincerity that what’s good for ourselves is also good for others. Opinion polls on the strength of the economy change seamlessly according to which political party is in power, and we will happily applaud behavior on “our side” which we just as quickly condemn from the other. When coworkers, friends, or family members connive to get their way over and against us, we might wish to denounce them with the fury of Gregory VII and Henry IV quarreling over bishoprics, but it would tarnish our outrage if we were forced to imagine them acting in sincerity, warped or otherwise. On first read, Erasmus’ portrayal of an unrepentant Julius II at the gates of Heaven seems all the funnier for its superficial exaggeration, but it may also work on a much deeper and more poignant level, as an exploration of how thoroughly we can all fool ourselves. We might like to hold such behavior at arms length, and easily write it off as the product of a bygone time, from which we’ve all learned and moved on from. But it may also be a product of the same crooked timber of humanity from which we all grow.

One of the medieval history professors I took in college was a devout Catholic, and he said he always had trouble visiting St. Peters in Rome, because he couldn’t look at the cathedral without thinking of all those poor German widows bilked out of their meager savings.

Peter Wilson’s “The Thirty Years War: Europe’s Tragedy” is an exhaustive and authoritative work, and a key part of the book’s framing is that religious considerations were increasingly subsumed under dynastic and political ones as the 30 Year’s War went on. He also discusses the tensions between the Habsburgs and the Papacy during the war.

Erasmus's portrayal of Julius in Julius Excluded from Heaven was a truly enlightening read from my perspective, as it was a portrayal written by someone who was a contemporary of the Pope.