On the Limitted Scope of Pre-Modern Historical Writing

Why "social history" was difficult to write in antiquity, and what this tells us about the rise of the modern world

This post builds on a previous essay on Tocqueville’s description of historical writing in aristocratic and democratic societies.

It’s generally understood that ancient histories were mostly written by, and for, members of the aristocracy and learned classes, creating a contrast with modern “democratic histories,” which attempt to tell a much broader story reflecting a cross-cutting of society (the lower classes, women, slaves, etc). Sometimes today this contrast creates an oppositional tension, as if one type of history were “better” than another, and you can find partisans casting stones about history written by and for rich (white) men, or revisionist histories which overthrow historical heroes and great figures. I’d like to side-step that debate, on the grounds that before we cast judgment on the past, we ought to try to understand the incentives and motives at work, which might reveal something interesting to us.

I think it’s probably something of a truism to note that ancient histories tended to be written by and for aristocrats and the learned classes. After all, ancient societies tended to have comparatively low literacy levels, and there simply weren’t many people with the leisure time and resources to read and write. The social roles and expectations of aristocrats also tended to reflect political and military careers, so histories focused on these themes (Polybius explicitly said that in order to write history well, an author needed practical experience as a statesman and general).1 Modern historians are correct to point this out and caution us that when Tacitus writes about the destruction of liberty under the Roman Emperors, he tends to mean the liberties of the senatorial class; the tyranny of Caligula or Nero was a bit more immediate and personal to a Roman senator than to a remote peasant in Gaul.

This trend continued in the middle ages and early modern period, with monastic chronicles primarily recording the lives of kings and important events in the church, although many hagiographies of saints opened up space for a new type of “elite” life (spiritual, rather than political or military). Well into the early-modern period, historical writing still served to help train the nobility, with Cardinal Fleury remarking that, “A man of mediocre status needs very little history; those who play some part in public affairs need a great deal more; and a prince cannot have too much.”

(As an aside, I think this general preponderance of pre-modern literature written by and for elite audiences still contributes to a general “lifestyle inflation” impression, where our notions of what it meant to be an educated individual historically tend to be skewed upward socially. Especially in classical education, or sub-cultures with a fondness or reverence for the past, we sometimes take the very top stratum of society as our default impressions of the past.)

Rather than simply portray the wider social lens of modern democratic history as either a rebellion against, or progressive improvement on more narrowly-defined aristocratic history, I’d like to pose, as a counterfactual, the difficulty of writing modern-style social history in the pre-modern world. Just how would an ancient historian have managed to write a “social history” about the life of peasants, women, or slaves?

We do have instances where historians tried to survey the culture and mores of other nations, such as the travelogue portions of Herodotus’ Histories, Julius Caesar’s descriptions of the Gauls, and Tacitus’ work on the Germans. But these are more in the vein of social commentaries on other contemporary peoples, and not attempts to explain a social change over time. Tacitus does not try to explain the tribal history of Germany over hundreds of years, nor do we have attempts from late Roman authors trying to document how the Germans of the 4th century were different from those of the 1st. Even when a historian such as Livy attempts to chart the mores of the Romans from the Founding of the Republic, we end up mostly getting a picture of what 1st century BC Romans thought about their own history.

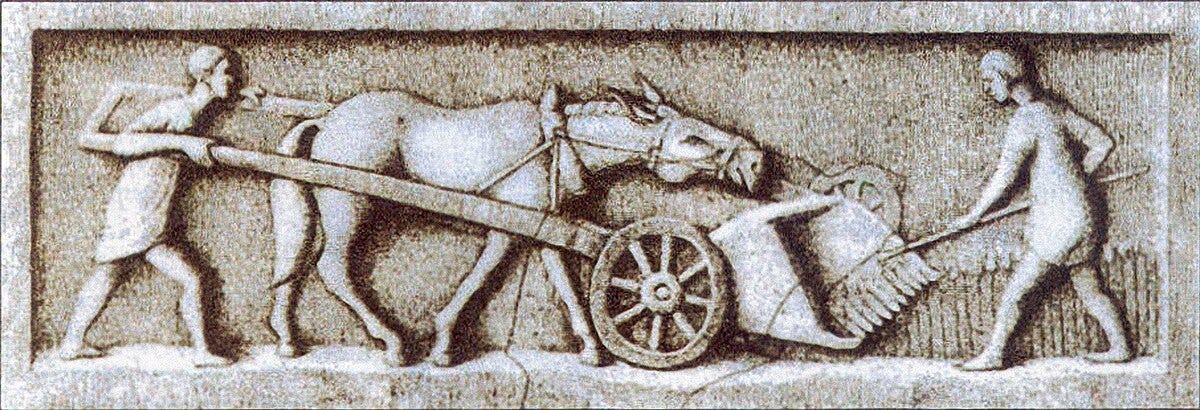

Instead, imagine how difficult it would have actually been for a historian to try to document changes in, say, farming practices over time. So many of the tools a modern historian might use for a social history, including archeology and ready access to archives of legal documents, didn’t exist. And, of course, a mostly non-literate society would have had far fewer private letters and diaries to access (and those that did exist, would be mostly written by the nobility). In theory, a historian could travel round to a host of different villages and listen to the oral histories of thousands of farmers accrued over generations, but this wouldn’t be easy, and would be of uncertain value. Without modern archeology or a denser documentary-record, a hypothetical ancient social historian would’ve been limited in what conclusions they could draw about changes in farming practices over time. Writing a feminist history would be similarly constrained, and even more difficult in terms of accessing sources, as women were generally separated from the public, and ensconced within the lives of families and clans (which, it should be noted, were often larger and more meaningful in scope than sometimes appreciated today).

In fact, as you work through the thought-experiment, you start to realize more and more how little “change over time” would have been readily apparent in an ancient social history. In most places on the globe, the pre-modern world was a world of subsistence farming, limited trade outside of cities and ports, and a world where very small elites competed for power. A farmer taken up from the Roman Empire and dropped onto an 18th century Italian farm wouldn’t have been terribly out of his depth, as both managed roughly familiar crops and animals, exported any surplus to the nearest town or city, paid rents or taxes to the local nobility, and enjoyed a dense network of relationships with family and neighbors. One of the few ancient historians to argue for some sort of grand “Capital H” change in history, is Polybius’ argument that the cyclical patterns of rising and falling Greek city-states, had been broken by the fundamental fact of Rome’s rise to dominance, leading Polybius to claim that his history alone was truly “universal.”2

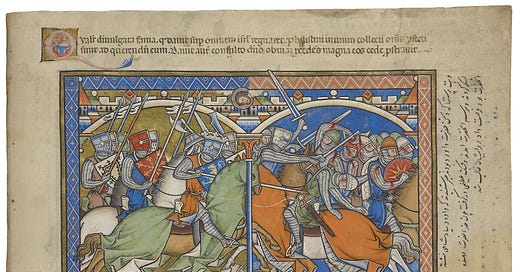

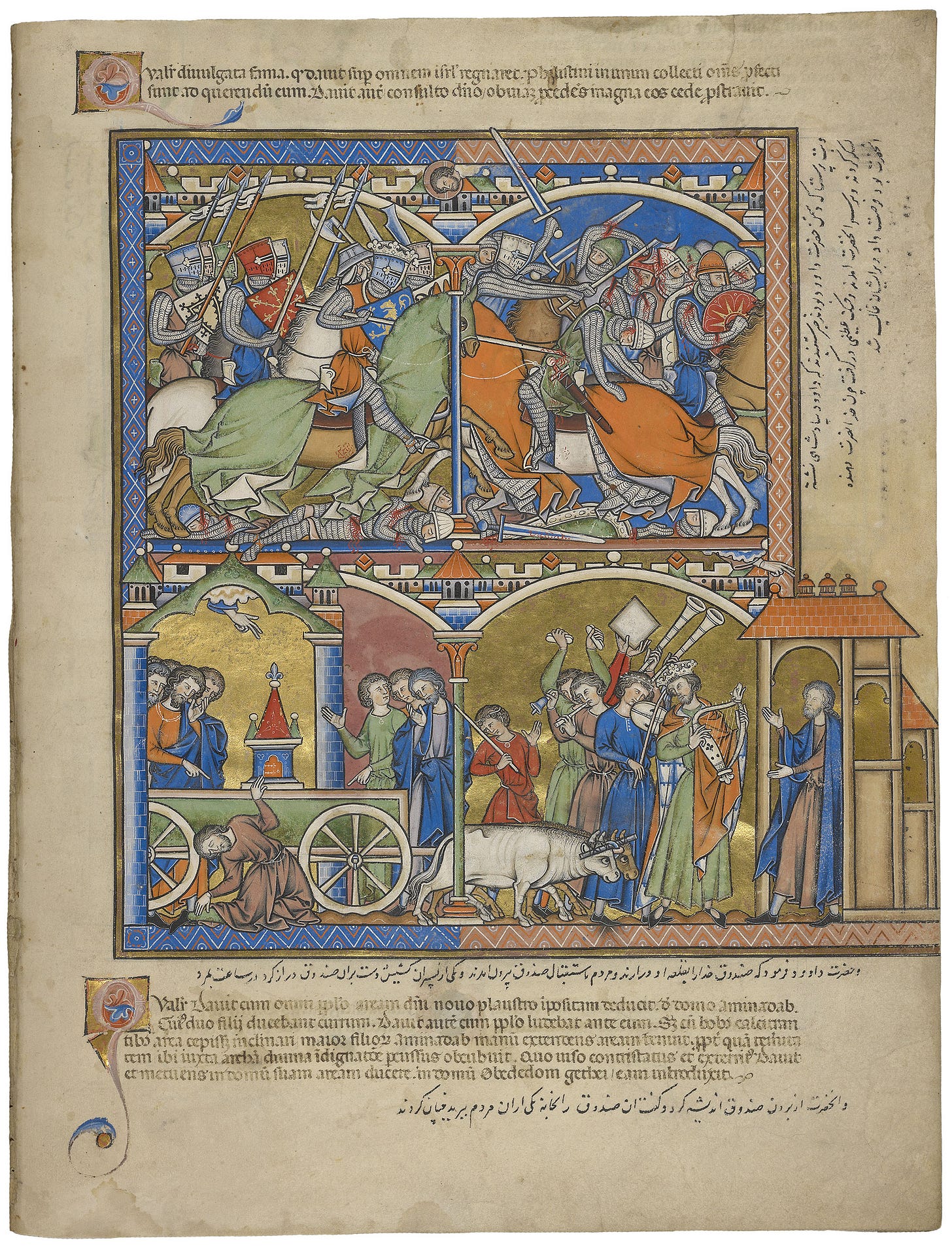

This not at all to say that there weren’t real and meaningful differences across and within pre-modern societies (the ability to chart land-use and family-size over time in archaic Greece, for example, has helped sharpen our understanding of the formation of the polis, and even explained a lot of what we know in the written record about political developments in those times and places). But these changes were probably harder to see at the time, and didn’t stand out as sharply. In fact, there’s good evidence from art that people in the past may not have even imagined other historical societies as materially very different from their own. Consider how medieval and renaissance illuminations and paintings so frequently depict foreign and ancient cities and peoples as looking essentially familiar. My own hunch has long been that some renaissance artists probably assumed that people and buildings in the Bible or Roman Empire looked different from their own day, but that they often had no idea of what that difference actually was. So you end up with Renaissance depictions of Christ on the Cross, flanked by very Renaissance-looking Roman soldiers. In fact, not knowing the historical differences probably helped reinforce the immediacy of lessons from the Bible or antiquity; as it was much easier for the illustrators of the Morgan Bible to depict Biblical Kings as Feudal Knights, or Raphael to celebrate Pope Leo saving Rome from Attila the Hun, by turning Leo (and his anachronistic Cardinals) into a very relatable Renaissance Pope. Ironically, when the differences of the past become less accessible, their lessons and individuals can appear much closer to the viewer.

If the pre-modern world appeared more static, then those changes that did stand out would naturally appear more important. If “capital H” history didn’t appear to change much, and if the subtler social forces of history (movements of population and climate, the impact of trade from thousands of miles away) were much harder to discern, then focusing on what was readily visible, and could be controlled, made all the more sense. This brings us back to the focus of aristocratic historians on politics and warfare, which now jump out in greater relief. And within the context of the pre-modern world, elite individuals did in fact exert far more power. Modern historians can chart the movements of peoples or changes in climate or trade, but to the ancients themselves, usually it was only a king, statesman, or general who possessed an outsized ability to cause or respond to events. Modern complex societies with professionalized institutions are designed to be much more interchangeable in terms of the quality of the individuals who operate them, whereas ancient and pre-modern politics usually depended much more on personal relationships, such as in feudal politics or early modern diplomacy. Consequently, it made sense for aspiring nobles and leaders to study the personal histories of rival dynasties, and the virtues and vices of historical role models. Not only did political leaders make up much of the audience of history, they were part of a much smaller segment of society positioned to act on that knowledge at a high level.

Admittedly, I’ve mostly been talking about history from a material and political standpoint, which is precisely where the modern world looks the most different from the past. You can, of course, find past philosophies of history which laid out theories of historical change and development, especially along religious lines, such as Augustine’s Six ages of the World schema using Biblical epochs. But if the bulk of historical writing in the pre-modern world followed politics and warfare, then the rise of modern democratic history and social history, highlights for us how much human society writ large has changed over the last five hundred years, as part of the “rise of the modern world.”

I hope to explore this topic next.

Polybius XII, 25d-25g

Polybius I, 3-4