Two years ago, I was asked to give a faculty-talk at a President’s Day faculty meeting. That morning, however, I went to school fairly sure that my wife was in early labor with our fourth child. I hurriedly typed up a rough outline of a talk on George Washington, all the while keeping one eye on my phone. Sure enough, I was happily called away. I only found out much later that our assistant headmaster had in fact read my notes out to the faculty for me. This essay is adapted from that outline.

Also, my old headmaster would want me to remind readers that today is not really President’s Day. The official holiday today marks Washington’s Birthday.

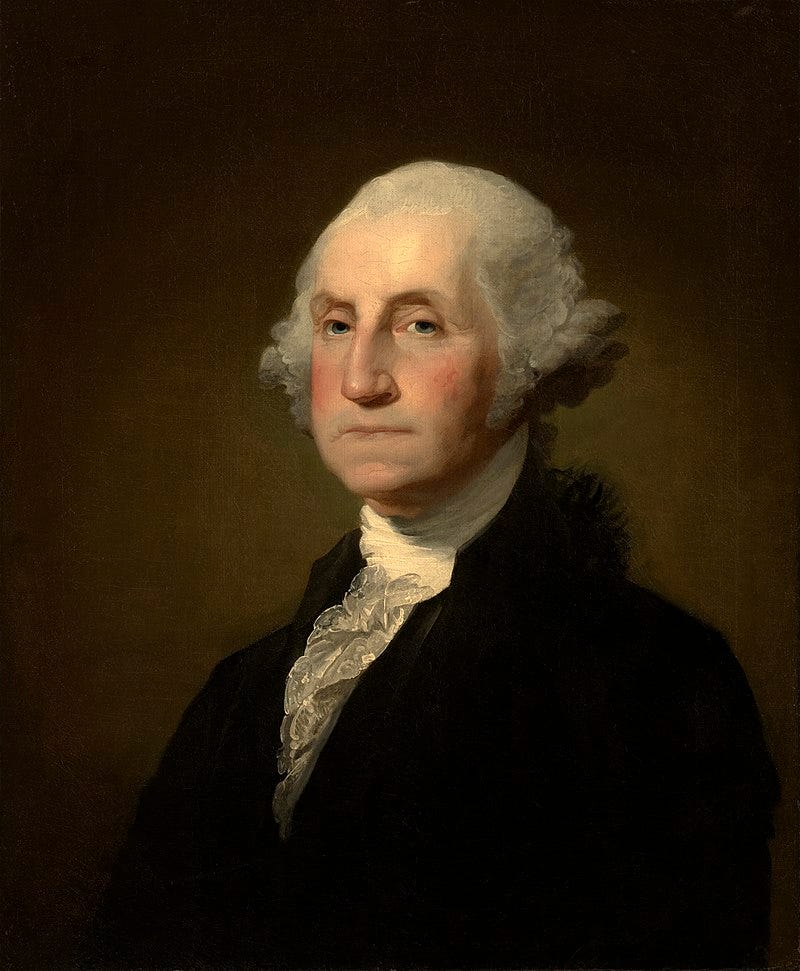

Wherein exactly lies the greatness of George Washington, dubbed “father of his country,” and “first in the hearts of his countrymen?” He commanded the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, and became our first President. Just as he was physically tall in life, Washington looms over the legacy of America as the foremost of the Founding Fathers.

But strip aside the hagiography, and the innocent myths about honesty and cutting down cherry trees. What exactly did he do that made him so famous?

As a general his battlefield record was…mixed at best. His most famous victory, at Trenton, amounted to a relatively small surprise attack which netted around a thousand prisoners, but resulted in less than thirty dead on both sides. Trenton’s main effect was political and psychological, in that it showed that the American army still had teeth. Washington’s largest set piece battle at Brandywine was a defeat, and his final great victory at Yorktown was a competently-executed siege made possible only by French naval superiority. Washington did not command at Bunker Hill, Saratoga, or Guilford Courthouse and Cowpens. For most of the Revolutionary War, Washington’s greatest achievement was simply keeping his army from dissolving, hence the iconic image of a dwindling band of shivering soldiers at Valley Forge. Probably his greatest act of raw generalship was his brilliantly executed retreat, shrouded in heavy fog, from Brooklyn to Manhattan after the Battle of Long Island. In other words, Washington’s greatest feat of arms came during a defeat.

Washington’s previous military exploits are hardly matters of legend either. His most famous action outside of the Revolutionary War was Braddock’s disastrous expedition into the wilderness during the French and Indian War. Previously Washington had had his command defeated and captured in his embarrassing operations around the desperately named “Fort Necessity.” One of the most consequential moments of George Washington’s life was his misunderstanding of the terms of surrender at Fort Necessity, helping start a global war which resulted in the eventual British conquest of India, and the rise of Prussia as a great European power.1

Politically, does Washington fare much better? Although he served two terms and relinquished power as the American Cincinnatus, his record in office is hardly the most impressive. Washington might deserve credit for modeling how the Executive branch would function, but then one could as easily say that he gets undue credit simply for having a first-mover advantage. The Jay Treaty helped avert war with Great Britain, but was unpopular at home. Washington helped defuse and put down the Whiskey Rebellion, and then pardoned many of the ringleaders. He presided over a quarreling cabinet, and managed to be the only non-partisan President in America’s history. Washington’s greatest speech, the Farewell Address, was mostly ghost-written by Madison and Hamilton. He has no law or proclamation equal to the Emancipation Proclamation, although he did proclaim the first national Thanksgiving.

Yes, George Washington gave up power after the Revolutionary War, and then retired after two terms as President. In other words, his most famous accomplishments are for what he didn’t do.

How does Washington compare to the rest of the Founding Fathers? Most of the other tier-one figures were men of ideas and letters. Franklin, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton, were all prodigious intellects in various ways. Although he was very intelligent, and possessed great practical wisdom, Washington could appear under-educated, as he himself was aware of. He had much less formal schooling than many of the other Founding Fathers, and as Ron Chernow puts it, he regretted and was anxious over his relative lack of Latin, Greek, and French. John Adams even once snobbishly disparaged him as “too illiterate, unlearned, unread for his station and reputation.”2

Notice that Washington chairs the Continental Congress. His job is to play referee and keep order, not be the architect and weaver of ideas. So what makes Washington so special, and why the reverence and awe surrounding him?

I have obviously been a bit provocative so far, and have downplayed Washington’s record somewhat unfairly, in trying to draw out a contrast. Because while a revisionist historical narrative could talk down Washington’s record into something pedestrian, it’s very clear that the reverence and awe around George Washington was not a hagiographic halo constructed after the fact, but a very real and present thing throughout his life.

From an early age, important figures gravitated towards Washington and marked him out as special. He was welcomed into the social circle around and mentored by the Fairfaxes, one of the leading families of the Virginia aristocracy.3 In his twenties, he was given command of colonial troops along the frontier.4 As a twenty-one year-old lieutenant-colonel, he was respected by his men even while holding them to high standards of dress and discipline.

Despite his outward composure, Washington’s inner personality was anything but cool. He possessed very strong feelings and a massive temper when roused.5 But he wrestled his emotions down and usually mastered them, with the same willpower that held a freezing and demoralized army together even as their terms of enlistments expired and the Continental Congress dithered about pay. During the French and Indian ambush of Braddock’s column at the Monongahela, Washington had two horses shot out from under him, and received four bullet holes through his hat and coat.6 As one of the few senior unwounded officers remaining after the battle, Washington road forty miles through the night to relay orders, all the while still weak from fever and dysentary.7 Washington’s considerable willpower was matched by his remarkable physical strength and stature, hardened by the rigors of life in the saddle as a surveyor.8 You can find other great leaders who led men successfully at a young age, often dashing figures like Alexander or Charles XII of Sweden, inspiring men through charisma and raw talent. But even as a young man, George Washington led like an old one. And he merely led instead of ruled, because he first ruled himself.9

It is this level of character and self-possession which stood out to everyone Washington met, and which built his reputation. His greatness and fame came from within himself, rather than simply his ability to seize the moment. His natural character and integrity more than anything else rallied others towards him, as during the Newburgh Conspiracy, when Washington’s act of pulling out his glasses and begging their pardon so humbled his mutinous officers: “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for, I have grown not only gray, but almost blind in the service of my country.”10 It’s not so much that Washington amassed a record of grand and glorious accomplishments, as that, time and again, everyone looked at him and said, “that is a man I want to follow.” And rather than for his ideas or words, his fellow citizens honored him “Father of his country,” for his very personage. The greatness of George Washington…was being George Washington.

Washington, A Life. Ron Chernow, 45. Chernow includes a quote from Sir Horace Walpole about the so-called “Jumonville incident,” in which Walpole said that, “The volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire.”

Chernow, 13.

Chernow, 16.

Chernow, 38.

Chernow, 14.

Chernow, 61.

Chernow, 60.

I recall a story once of Washington breaking up a fight by riding into the brawl, grabbing two of the ringleaders by the collar, and physically lifting each of them off their feet. Another feat of strength was recounted by visitors to Mt. Vernon, who were amusing themselves by throwing an iron bar as far as they could across the lawn. Washington joined them and, “requested to be shown the pegs that marked the bounds of our efforts; then, smiling, and without putting off his coat, held out his hand for the missile. No sooner … did the heavy iron bar feel the grasp of his mighty hand than it lost the power of gravitation, and whizzed through the air, striking the ground far, very far, beyond our utmost limits. We were indeed amazed, as we stood around, all stripped to the buff, with shirt sleeves rolled up, and having thought ourselves very clever fellows, while the colonel, on retiring, pleasantly observed, ‘When you beat my pitch, young gentlemen, I’ll try again.”

When Benjamin West told King George III that Washington planned to resign his commission and return home at the end of the war, the King scoffed and said, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” Well then.

Contrast this with Napoleon’s confrontation with Marshall Ney and the regiment sent to arrest him upon his return from Elba. There was incredible bravery and ego, in Napoleon’s brazen “If there is one among you who wants to kill his general, his Emperor, here I am.”

I was looking for a source to learn more about history, trying online but you just happened to be answes to my prayers.

Jefferson writes of Washington, after slighting his intellect, that "perhaps the strongest feature in his character was prudence, never acting until every circumstance, every consideration was maturely weighed; refraining if he saw a doubt, but, when once decided, going through with his purpose whatever obstacles opposed. his integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives of interest or consanguinity, of friendship or hatred, being able to bias his decision. he was indeed, in every sense of the words, a wise, a good, & a great man."

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-07-02-0052

Matt Spalding argues in an essay in this volume that we don't understand Washington anymore because we don't understand prudence or magnanimity anymore:

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Leisure_with_Dignity/nQXsEAAAQBAJ?hl=en