Historical Determinism, Structuralism, and the Role of Contingency in History

Pt 3 on historical laws and teleology

Continuing our look at history as a discipline, let’s return to the question of historical determinism, and whether or not there are “laws'' in history. Recently, we’ve talked about why the 19th century had an overly triumphal view of history that was shattered by WW I, and how Herbert Butterfield critiqued the teleology of Whig History.

But we haven’t proven that there aren’t general laws in history yet. Maybe the science-envy of the 19th century wasn’t misplaced after all? After all, plenty of successful innovations have followed numerous false-starts, and the tools of empirical research and quantitative analysis have significantly aided our understanding of many endeavors.

Determinism -

Americans don’t always look for large forces that can shape and determine outcomes. The narrative of a frontier society founded upon a revolutionary break from the old world (which traditionally invites immigrants to come to America and reinvent themselves anew) has an imaginative hold on the national mythos. Arguably, inhabitants in much of the rest of the world might more readily intuit just how powerfully their histories have been shaped by very large forces, which are usually outside of their control.

And at more than just a first glance, you can find a lot of evidence for large scale trends and fixed forces that defy easy contravention. Geography, economics, culture, technological trends, and much more can all exert a surprising amount of persistence in a society for a remarkably long time. Even individual lives are measurably influenced by their environment; children raised in poverty are more likely to stay poor themselves, while the children of parents with doctorates are much more likely to be academically successful (and both examples are not simply determined by parental genetics). In the face of such large forces, individual agency can seem rather insignificant.

Arguably, the influence of geography upon history remains much underappreciated, especially in a modern world where we rely so much on the written world to shape our perceptions of reality, and where we think technology has flattened and shrunk the world. You can actually take quite a few places in the world, and seem to explain much, if not the majority, of their history simply through geography. Ancient Egypt and the Nile river is the classic example and perhaps clearest example here.

You could plausibly claim that Great Britain’s relatively lack of an internal standing army (not needed when you have the world’s greatest navy) gave the government less leverage over its populace, leading to greater liberties and lower taxes, which were then carried over as cultural attitudes to the American colonies, creating America’s fondness for smaller government and lower taxes. Russia, on the other hand, has always needed a strong central ruler to maintain any kind of order or defense in the face of numerous foes from all directions, meaning that Russia will always need something approximating the Czars if it is to exist at all. The Sahara desert, lack of good ports, tsetse fly belt, and Nile river cataracts all contributed to cut Sub-Saharan Africa off from much of the rest of world for long periods of its history, leading to less economic and political development. Asian cultures which grow rice are more communal and less individualistic than Western cultures that grow grain.

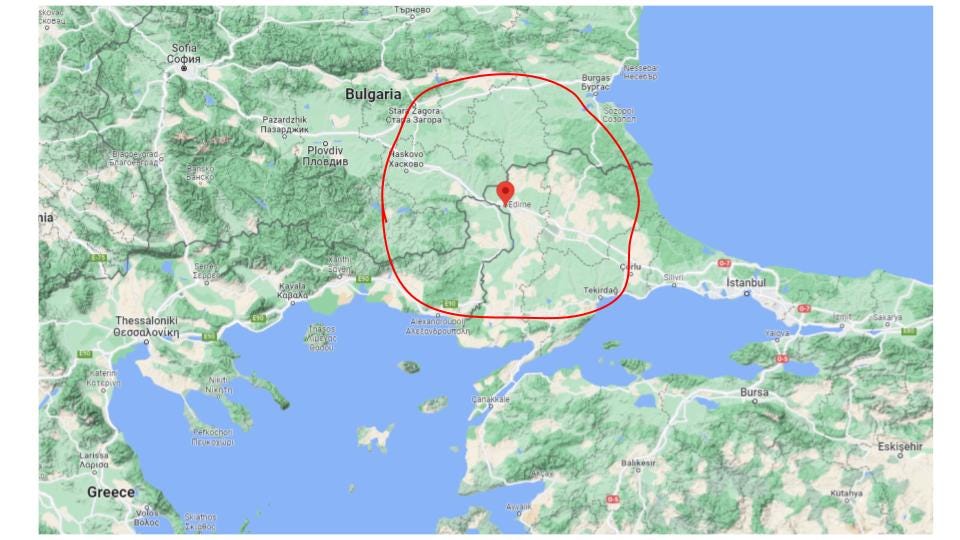

Military history has been much less susceptible to the notion that the world has “shrunken,” and that geography no longer matters. John Keegan described the area in the Balkans around Adrianople (Edirne, Turkey) as “the most contested spot on the globe,” and listed 15 separate major battles fought near there, as armies throughout history tried to move through the major land routes between Europe and Asia Minor. Much of the current Russia-Ukraine conflict can be interpreted through the geographic need for Russia to extend its borders as far from its heartland as possible, and off of the easily traversable plains of the Western Steppe.

Putting too much emphasis on national or cultural stereotypes is fraught with peril, but it should be obvious that the cultural patterns of French cooking or German engineering might rub off on someone raised in those environments. At least some of America’s dynamism, tolerance for failure, and even levels of violence, can be traced back to the history of an immigrant population made up of individualistic risk-takers. Almost by definition, most of the cautious and orderly folks stayed in the Old World. The very nature of America’s revolutionary impulse towards remaking ourselves may be…geographically and genetically determined.

Structural theories of history -

Determinist narratives don’t just work with geography or environment; there are plenty of apparent trends that seem almost “law” worthy in human societies. At least as early as Plato and Polybius, ancient writers noticed apparent cyclical patterns (anacyclosis) that could be mapped onto historical states; a cycle of regime change as states passed from monarchy, to aristocracy, democracy, and then anarchy, before the process began anew.1 Polybius and Aristotle could both point to concrete examples showing the pattern at work, and a version of this survives in popular fears about “good men, good times, bad men, bad times,” decadence.2

Early and Medieval Christians actually developed the practice of interpreting history in stages into a high art. Augustine most famously divided history into six/seven stages that mirrored the days of creation in Genesis, and versions of this delineation remained popular through the Reformation. Joachim of Fiore popularized a division of history into three ages (corresponding with the Trinity), and other writers found all sorts of complicated symbols and parallels in the Bible and church tradition that they used to map onto their own day and age. Indeed, the very notion of an “end times” and Day of Judgment that History is working towards (with endless debate about the exact mechanics and details) is arguably still at the root of our modern linear conception of history.

In fact, the revolutionary spirit of first the Bastille, and then later Hegel and Marx, simply takes this Christian providential framework, and turns the Day of Judgment into a human event, a case of immanentizing the eschaton.

Speaking of the Marxists…for the last couple of posts on this topic I’ve occasionally mentioned them as one of the arch examples of teleological and triumphal “Capital H” history, and yet they’ve mostly survived criticism so far, while we’ve talked about the end of triumphalism and collapse of Whig history during and after WWI.

Unlike Whig history, Marxist history actually gained strength after WWI. Prior to the Great War, Marx’s prophecies of the coming Workers Paradise had not panned out. But with the rise of the Soviet Union and the seeming success of central planning in the face of the economic chaos of the 1920’s, Marxism got a new lease on life. Institutionally, Marxist scholarship gained in strength throughout the mid-20th century. Even as Reagan was cheerfully talking about morning in America, it was not hard to find even non-Marxist experts and academics in America still prophesying that central planning could match western capitalism.

These days, there are not many old-fashioned Marxist true-believers left; the eschaton has not immanentized. Yet critical interpretations of history and society using versions of Marx’s views on class conflict and materialism are still easy to find; one can still have a Marxist view of history without expecting history to End anytime soon. In fairness, there ought not to be anything wrong in interpreting history through the lens of class and group conflict when the situation actually calls for it. This issue, as with most any ideological theories, is when adherents start jamming square pegs into round holes with their evidence.

Modeling complex systems -

Geographic forces and ideological theories of history can be incredibly useful tools for understanding history, and the average American is probably a little too unaware of how much historical forces and trends have shaped and influenced their lives without their having much say in the matter. Culture war fights about structural “isms” of oppression generate far more heat than light, but the basic idea that past conditions will have present repercussions (poor neighborhoods will remain poor, groups with less access to opportunity, infrastructure, and education, will have a harder time of things, etc.) is actually something that most people can probably come to agree on fairly easily, if only it could be stripped of its partisans priors and baggage. Granted, what to do about historical and systematic inequalities is another matter.

And yet, we cannot go very far in deriving general laws and principles about history from these broad trends and forces, for two reasons.

The first reason is that human societies are incredibly complex systems, and defy easy modeling. It was understandable that social scientists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries hoped that scientific laws for human society could be find, similar to those of Isaac Newton, but even as the early Progressives and central planners were laying out their spreadsheets, Einstein and the hard sciences were moving away from Newton, and into relativity and quantum mechanics. Ideas like Chaos Theory (popularized by Michael Crichton in Jurassic Park)3 have popularized the idea that very complicated systems behave in extremely unpredictable ways.

In The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb offers a thought experiment using billiard balls to illustrate how difficult it can be to predict events that rapidly multiply in difficulty (the original calculations were done by mathematician Michael Berry):

“If you know a set of basic parameters concerning the ball at rest, can compute the resistance of the table (quite elementary), and can gauge the strength of the impact, then it is rather easy to predict what would happen at the first hit. The second impact becomes more complicated, but possible, you need to be more careful about your knowledge of the initial states, and more precision is called for. The problem is that to correctly compute the ninth impact, you need to take into account the gravitational pull of someone standing next to the table…and to compute the fifty-sixth impact, every single elementary particle of the universe needs to be present in your assumptions! An electron at the edge of the universe, separated from us by 10 billion light-years, must figure in the calculations, since it exerts a meaningful effect on the outcome.”4

Note that we haven’t even begun to worry about a scenario where some balls are already moving, and that this is for a very simple system that’s mostly closed, where almost every immediate variable is known and controlled. But it gets worse. Even if we had a supercomputer powerful enough to model an entire economy, we’d still be met with the problem of human agency and free will.

Human behavior can be moderately predicted according to statistical data sets. Education, health, wealth, religion, etc., can all offer predictive power on a simple bell curve, with a few outliers at each end. But just knowing the overall behavior of a group doesn’t actually tell us much about actual individuals in the group; we don’t know who in the group will end up in the 40th or 60th percentiles. And while the “tails” at each end of the bell-curve are small, the impact of individuals in those ranges can be tremendous (in what Nassim Taleb calls “extremistan”), precisely because they become so non-representative. A person in the 99th percentile may die in a random car crash, live a life as an unrecognized genius, be a successful professional who ultimately leaves little impact, or be Alexander the Great himself. The range of possible outcomes is vast, and seemingly unpredictable.

Perhaps we say it doesn’t matter so much, because of our big trends and forces in terms of geography and environment. And I would agree that large trends and forces can significantly shape and constrain human agency and choice. Napoleon was lucky to be born in a time when politics and war would enable his stunning campaigns of maneuver with massed armies, in a way that wouldn’t have been possible two centuries previously. Yet just because we can say “the conditions were more likely to produce a Napoleon in 1800 than in 1600” doesn’t begin to account for the myriad number of variables we’d need to account for in assessing the different possible outcomes. You could run the life of Napoleon a hundred times and get vastly different outcomes for both Napoleon and Europe in many of them (and, actually, we can’t run that simulation a hundred times, which is precisely the problem).

The role of contingency -

Ultimately, history is both shaped by trends and forces, but also contingent upon chance and human agency. Sometimes, the outcome of a war appears predetermined by the relative strength and resources of both sides, and other times Alexander the Great barely survives the Battle of the Granicus River because a Persian axe blow came within seconds of changing history.5 On paper, Allied men and material made ultimate victory in the Second World War appear foregone, but in June of 1940, with some voices in the British cabinet urging negotiated settlement with Hitler, Winston Churchill’s personal leadership and vision really mattered. Even if Allied victory was largely predictable, the shape and subsequent reverberations of that victory were highly contingent upon the personal relationships and decisions of all the major figures. What if Roosevelt hadn’t been so taken in with “Uncle Joe,” and, like Churchill, been more wary of the USSR? What if Truman had decided not to drop the Bomb, or what if the Japanese Emperor hadn’t personally intervened to force Japan’s surrender? Statistical models can usually predict the outcome of the World Series with greater than 50/50 accuracy, but the games still need to be played.

We can look at trends and patterns, and say, “based on historical examples and conditions, a certain range of outcomes might be more or less likely,” but we should always be wary of the quality of our inputs, and even a simple bell-curve model where rare events occasionally happen will have dramatically outsized effects. If a great pandemic occurs once a century, and has a 1% of happening every year, it would be possible to predict something like Covid, but that would still leave us not knowing who would be the President of America, or the state of society and technology, making the actual strangeness of the year 2020 impossible to predict. Unless we can generate a theory or supercomputer that can model the entire universe, and also account for human agency and will, we are not likely to find true “laws” of history in the same way that Newton developed laws of physics. Maybe the Medieval theories of history dependent upon Providence were on to something.

I’m simplifying a bit between the two versions, which are slightly different. Polybius has alternating good and bad versions of each stage; monarchy (then tyranny), aristocracy (then oligarchy), and democracy (followed by ochlocracy).

I won’t really get into this trope here, as it might make for a good post at a later date, but I think this meme should be treated carefully, and is, at the very least, not clear cut. Its use often obscures more than it helps.

Just because I don’t want to put out an air of false mastery, I’ll be quick to say that my detailed knowledge of Chaos Theory doesn’t go much beyond what I read Jurassic Park in the first place).

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan, Random House, NY, 2010. Kindle Location 3628

Figures like Alexander the Great and Ghengis Khan are excellent examples of how individual agency can shatter the course of large and impersonal trends. It would’ve been easy to predict a continued world where Greek culture and the Persian empire coexisted, or one where the various steppe nomad tribes continued to swirl around the periphery of the settled Eurasian kingdoms. It would probably flatter both conquerors greatly to know how their very persons defy attempts at prediction.