Last time, we looked at the famous George Santayana quote about repeating history by failing to study it. While there’s much to be said for this approach to studying history, it also has some serious limitations and pitfalls. In this post, I’d like to offer a different framework for studying history, one which does include “learning historical lessons,” but goes further, and is in fact the special and unique domain of history as a field of study.

The notion of learning and applying lessons is actually a general feature of all philosophical disciplines, and is not unique to history. When we read Shakespeare, Plato, or Livy and use these works to “better ourselves,” we engage in much the same type of enterprise, just across different sub-fields of philosophy. Learning from Othello is functionally quite similar to learning from any real historical character. What differs is the domain of content.

The special provenance of history is the past, so we’ll start very simply by looking at the implications of that domain. The word itself was first used to refer to the study of the past by Herodotus, who applied the Greek word “historia,” which simply means “inquiry.” For Herodotus, his inquiry was the cause of the Greco-Persian Wars (which he actually tried to trace back to the Trojan War and the kidnapping of Helen). The first task of history is to posit “what happened, and why?”

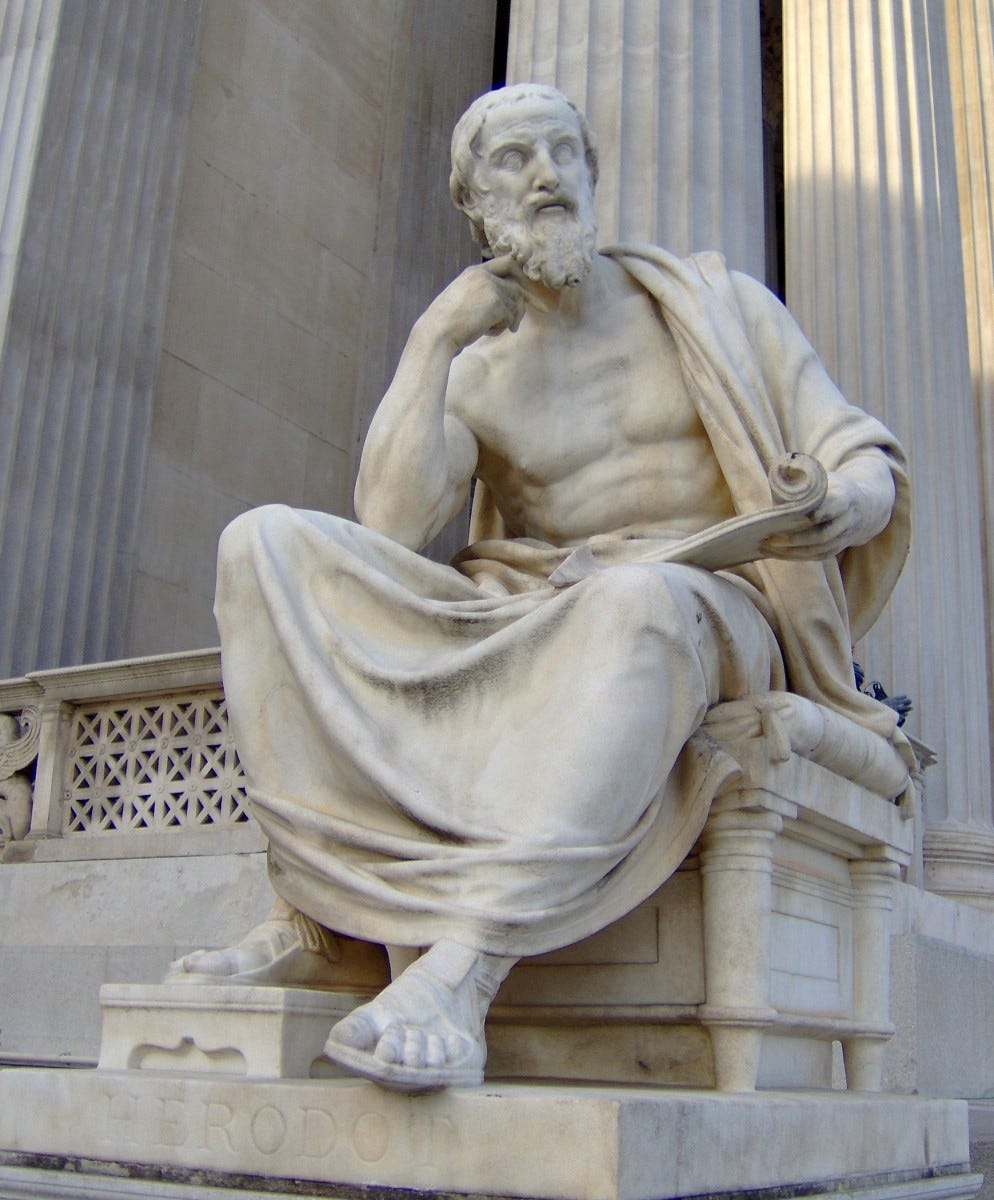

In its simplest form, historical inquiry starts from looking at the world around us, or something we encounter in it, and asking “what and why is this?” Implicit in this question is the causal relationship between past and present, as historical inquiry tries to uncover a chain of events which can explain the origin or nature of present circumstances. As geometry studies objects in relation to the three spatial dimensions, history focuses on the fourth dimension (time).

The special task of history, then, is to tell us how the past creates the present.

As with the “historical lessons” model of historical study, the inquiry model is also something we constantly use in our daily lives. When we first meet a person, or encounter something unknown to us, part of our attempt to get to know the subject is to find out personal history or backstory. Consider a time when you learned about someone’s personal life story, and discovered a key piece of context that made their personality snap into clearer focus. If you meet someone who seems rather frightened of bear attacks and think “hmm, must be a story there,” you are beginning the process of historical inquiry. Note also the word “story” gets at the nature of history as piecing together narrative, which is a fundamental human trait for understanding reality. Models of historical causality, like mathematical equations and empirical observations, are essentially fancy ways of telling a story.

- The past creates in the present tense

There’s an odd bit of grammar in the idea of the past “creating” the present, but I use it deliberately. The past didn’t simply “create” (using the past tense) present circumstances. We should very much think of past events as continuing to create in the present tense. Events and individuals are shaped and molded by chains of causality which, while lying in the past, continue to reverberate in the present. While we only experience instantaneous moments in the present, we are creatures who exist in time, and true understanding of ourselves requires seeing ourselves across that fourth dimension. Just as our bodies literally are what we eat, so too are we the present result of past influences, as anyone who has trouble shrugging off a traumatic experience can attest. This is as true for individuals as it is for entire civilizations.

Contemplate the impact of past influences on our lives long enough, and you might even feel a bit trapped by them, as past events dictate present circumstances and bound off our future possibilities. A near all-nighter spent binging Netflix instead of doing homework will create a different range of available choices and possible outcomes for the next day, no matter how much we might later wish differently. The greater shape of our lives can be powerfully dictated by large and impersonal events that we have little control over.

Imagine a crop failure in Eastern Europe sometime in the late 19th century, which spurred a family to immigrate to America through Ellis Island. Sometime later, the family moves to Detroit to take advantage of work in the nascent automobile industry. Personal experience with automobiles as a child nudges a member of the family to study engineering in college, and then move out to the West Coast during the Second World War to work in the growing aerospace industry. Half a century later, members of the family move to the Sun Belt in the American South to take advantage of better economic and business opportunities. Along the way, generations of individuals in this family will have all manner of life decisions (potential jobs, schools, spouses, health outcomes, etc.) impacted by a myriad number of variables, which may range from giant systemic trends in global macro-economics, down to the most improbable random chance. The same individual life may seem both entirely predictable, and genuinely one-in-million.

- Integrating the two historical approaches

If we ground the study of history as the story of how the past creates the present, then the “historical lessons” model of history is not rendered invalid, though it may show itself to be more of a secondary benefit (at times at least). When faced with a future decision or action, history doesn’t simply offer examples of “what has happened in previous situations that look superficially similar.” It can also directly help answer the question of “what is this situation and where did it come from?” Notice that this also, just as with the “historical lesson” model of history, can help improve our decision making and judgment.

The direct “historical inquiry” approach can also help address some of the pitfalls of “historical lessons'' that we talked about last time. Again, we find humility making an appearance, reminding us that each situation and event is distinct, and subject to a unique combination of large forces and contingency, which may limit just how far any particular historical lesson ought to be applied. As with appeasing Hitler and Saddam Hussein, the differences may be more important than the similarities. Also, the task of following the historical record from the past to the present puts the event in its proper context to begin with, helping cut down on the dangers of historical cherry-picking and motivated reasoning. Motivated reasoning is still a pitfall to beware of, as there is always a danger of reading into the historical record the explanations or motivations we want to find in the first place.

The fact that historical inquiry begins with some form of “what and why is this?” question, means that we expect our answers about the past to have some bearing on the present. This can be a pitfall, as we have to always remember that, unlike our historical actors, we usually know how the story ends. It requires a greater leap of historical imagination to put ourselves inside the minds of human actors who don’t already know the outcomes of their own decisions, and we have to remember that contingency means that historical events didn’t inevitably have to turn out one way or another. What decision was “correct” in one situation may not have worked in another, even when most other variables are the same or similar (in baseball, a manager calling a sacrifice bunt that ended up working, doesn’t necessarily mean it was the correct call based on the odds).

It can also be a disservice to the past if we treat it as a mere tool for the present; there is value in studying past events for their own intrinsic worth and merit. Past actors weren’t doing things simply for our own sake, and are not abstract pieces of data for a model or simulation. The historical record is full of real people of real moral worth and dignity, doing compelling things worth studying for no other reason than the sense of satisfaction and pleasure it can reward us with. The past can inspire, enliven, succor, warn, and give hope to us. Here, the “historical lessons” model of history as a subset of human philosophy should dramatically return for a moment and take its proper and deserved place in the spotlight. In the classical tradition, humans ultimately aspire, through all our tools and disciplines, to the transcendentals of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty (sometimes expressed as Unity). Although understanding the human record is fraught with myriad uncertainties, history can occasionally leap upwards from the particular and contingent, and offer glimpses of the general and universal.

This ability to teach universal truths is hard-won, and rarely achieved. Most of the time, when someone says, “history teaches us that….” whatever follows is likely to be at best a generalization of only limited utility, and often just a cherry-picked series of observations in service of someone’s pet theory.

- Studying the past in order to become a free individual

Let’s close by returning to the task of understanding the present, and dwell on the fact that each of us is a person of individual agency, but acting in the context of a huge number of influences and forces which beat upon us. Everything about us, from our ideas and assumptions about the world, down to our physical, mental and emotional habits, quirks, and tastes, aren’t simply the outcomes of our own opinions and decisions. Our patterns of speech are the result of centuries of linguistic drift and development. Our political ideas are generally borrowed (often half-understood at best) second or third-hand from an incongruous mix of past thinkers who were themselves responding to an entirely different set of ideas and arguments in a very different historical context. Even our tastes in food and fashion are shaped and constrained by culture, economic trends, and the influential decision-makers that we may know nothing about. And all these things also apply to our parents and friends in their influence upon us as well. If you dwell on it long enough, you may start to wonder just how “free” we really are, if the range of choices available to us are sharply limited by forces outside our control. We don’t choose our parents or what language we speak as children, and many of our childhood habits and tastes can only be changed later with great effort. A person on a subway is “free” to get off the train, but only at a narrow set of predetermined stops.

The terms “classical” and “liberal arts” education are sometimes used as complements to one another. In the classical world, a “liberally educated” individual meant a free individual; in contrast to one who received training in the “servile” arts, generally versions of manual labor. To have “libertas” meant that one was a free citizen (usually in a city-state), thereby owning property and having the privileges and duties that came with citizenship. But more deeply, to be “free” in this context also meant that an individual had mastery and agency over their own lives, in contrast to a slave, or other individual who lacked citizenship status. So, to receive a “liberal education” may have simply meant “the type of education given to free individuals,” but it also meant “education designed to make you free;” to make you a better citizen, and someone with more agency over one’s own life. The ultimate expression of this was probably the philosophical training represented by Socrates, or the Stoics or Epicureans. To have knowledge about the world, to know how to speak well, to understand the influences upon you, and to have the power to act against them or with them, were all marks of the flourishing and free individual.

Becoming a free human being, then, requires knowledge of how our present selves and present world have been created. The more we understand how the past creates our present, the more power we have in it. History is an essential part of becoming an educated, and free, individual.