How Boethius Regained His Citizenship

On the Republic of the Mind in the Consolation of Philosophy

In my series on liberal education, I referenced education as forming a sort of civic body offering “membership into that polis wherein all citizens are free, and freely educated.” I’d been thinking this through chiefly in a historical and institutional sense over several months while chipping away at the essay, but it turns out I could’ve just gone back and reread Boethius and saved myself much time and effort. In The Consolation, Lady Philosophy invokes the political imagery of a community of educated and self-mastered individuals to refer to Boethius as a philosopher. The fact that I spent months thinking through the problem from a historical and institutional sense, only to arrive at the same answer, feels like a proper Boethian unfolding of fortune and Providence in harmony.

As an aside, if you are not familiar with Boethius and The Consolation of Philosophy, I cannot recommend it highly enough. The Consolation is one of my very favorite books to teach each year, and has generated the best and deepest conversations with students I’ve ever had. I think it’s especially good for teenagers to read, as it offers a powerful frame for thinking about suffering, emotions, reason, and cultivating agency in one’s life. It’s also one of the most important books of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Along with works like Augustine’s City of God, and Macrobius’ Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, it’s essential for unlocking an understanding of the medieval imagination, and the medieval understanding of the cosmos that Dante ultimately unveils in The Divine Comedy. Alfred the Great worked on his own translation of the book into Anglo-Saxon (from what I understand, it’s a very different work in many ways), and C.S. Lewis is reputed to have said that in order to understand the Middle Ages, one must read Boethius. For that matter, the moral, providential, and cosmological visions of Lewis and Tolkien are undergirded by Boethius’s concepts of free-will, fortune, and providence. If you read Boethius, you’ll appreciate Lewis’ Narnia Chronicles all the more, and you’ll see exactly what Lewis is doing in his misnamed space trilogy (it’s a celestial trilogy). Tolkien’s Middle-Earth also turns on this interplay of free-will, chance (“if chance you call it” as Gandalf says), Providence, and the fact that even when Evil thinks it’s playing its own tune, it’s merely riffing on Illuvatar’s grand theme.

Anicius Manlius Boethius (480-524) was a late Roman senator, consul, and philosopher, who served in the court of the Ostrogoth king Theodoric the Great. While technically occurring after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Ostrogothic Italy remained essentially Roman in its culture and civic life, with the Gothic kings claiming legitimacy as rulers of Italy on behalf of the Eastern Roman Empire at Constantinople. It was for his alleged intriguing with the Eastern Empire that Boethius was ultimately overthrown by his court rivals, accused of treason, and sentenced to house arrest, before his eventual execution. While in prison, Boethius wrote The Consolation of Philosophy as a dialogue between himself and the personification of Philosophy, as a way of working through his suffering and misfortune. The entire work is richly deserving of a much longer treatment.

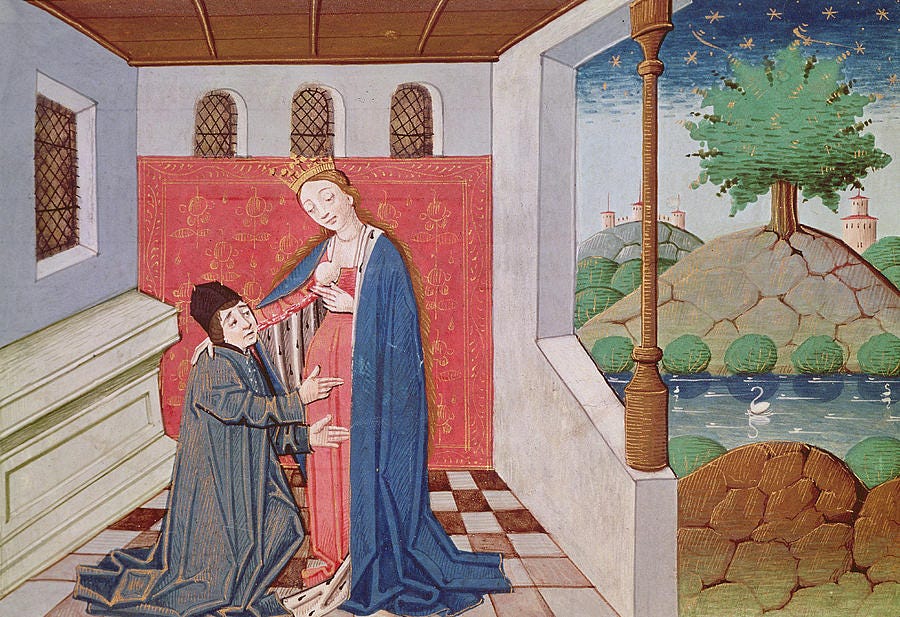

As The Consolation opens, Lady Philosophy appears in Boethius’ room, chases out the seductive muses of poetry who have been stoking Boethius’ passions with false comfort, and uses the fold of her imperishable robes (wrought with her own hands long ago in Athens) to wipe away the tears of worldly concern that cloud Boethius’ eyes, preventing him from recognizing his old teacher. Boethius asks Lady Philosophy why she has come down from heaven to join him in his “lonely place of banishment,” and if she is to “suffer false accusation along with me?”1 Philosophy scoffs at this, saying that attacks at the hands of fools are nothing serious, and mentions other persecuted philosophers, including Socrates and Seneca.2

Asking Boethius the philosophical version of a physician’s “tell me where it hurts,” Philosophy inquires into the cause of his unhappiness. Boethius launches into a “long and noisy display of grief,” as he pours out his sob story, relating how fortunate he’d been as a statesman and aristocrat, and how unfair his betrayal was at the hands of his court enemies.3

After listening to Boethius’ pity-party, Lady Philosophy begins her diagnosis, complete with a “well, this is even worse than I thought” comment. She tells Boethius that, yes, he is in fact banished and exiled, but not in the way he thinks:

“It is not simply a case of your having been banished far from your home; you have wandered away yourself, or if you prefer to be thought of as having been banished, it is you yourself that have been the instrument of it. No one else could ever have done it. For if you remember the country you came from, it is not governed by majority rule like Athens of old, but, if I may quote Homer, ‘One is its lord and one its king;’ and rather than having them banished, He prefers to have a large body of subjects. Submitting to His governance and obeying His laws is freedom. You seem to have forgotten the oldest law of your community, that any man who has chosen to make his dwelling there has the sacred right never to be banished. So there can be no fear of exile for any man within its walls and moat. On the other hand, if anyone stops wanting to live there, he automatically stops deserving it.

And so it is not the sight of this place which gives me concern but your own appearance, and it is not the walls of your library with their glass and ivory decoration that I am looking for, but the seat of your mind. That is the place where I once stored away–not my books, but–the thing that makes them have any value, the philosophy they contain.”4

Yes, Boethius is exiled and in prison, but he banished himself when he let outside passions and worldly concerns unseat Reason as the ruler of his mind. Losing his composure and self-control, he became captive to his sufferings and misfortune, wallowing in bitterness and recriminations. This is a punishment and exile which ultimately only Boethius could sentence upon himself.

The prison and banishment imagery for being held sway by the passions and emotions works well. You can see it in every toddler’s outburst when they don’t get what they want, and we can probably all remember times we were overwhelmed by strong emotions and grievances which we couldn’t shake off (or worse, didn’t want to shake off). In Latin, the passions (Passio as a noun, Patior as a verb) were often expressed in the passive voice. Passions aren’t things we do; they are things which happen to us, as when we say “I couldn’t help myself, something came over me.” You can probably see why this ground offers fruitful discussion with high school sophomores.

However, I want to turn back to the political imagery Lady Philosophy uses, describing philosophy as membership in a community. Twice in Book One of The Consolation, Philosophy refers to this country having walls and ramparts behind which the educated can defend themselves, evoking the imagery of a city. She also refers to other philosophers as her own, clearly linking them together under a common identity. This polis even has political parties and factional strife, as Philosophy’s robes are torn in places where the Stoics and Epicureans have fought over her, taking away only fragments of the Truth.5 It’s easy enough for us to understand philosophers as being vaguely united in a common bond, as individuals engaged in the same project, even when spread out across time and place. But for modern audiences, our social and political identities are not strongly linked to membership in a city, whereas to an ancient audience, allusions to a civic body and the physical walls of a city as a place of refuge would carry much more weight.

Also, Lady Philosophy is clearly positioned as the head or patroness of this community, similar to the patron deity of an ancient city-state (you can’t be a good Athenian without worshipping Athena). When she first appears to Boethius and angrily chases out the muses of poetry, Lady Philosophy refers to Boethius possessively, saying that if the muses had seduced any normal man, “it would matter little to me–there would be no harm done to my work. But this man has been nourished on the philosophies of Zeno and Plato.”6 Philosophy has come to rescue one of her own citizens.7

I don’t think we should automatically view Lady Philosophy’s patron status as suggestive of Boethius being a closet pagan, or a pure Neoplatonist. Modern views on religion tend to flatten out the spiritual realm and imagine One God alone, whereas the ancient and medieval cosmos was alive with spirits and powers. Even if Boethius is still perhaps a cult-member of Philosophia, the entire point of the work is to show how all things and all powers move in harmony under direction of Providence. Boethius’ cosmos is far too large for just Lady Philosophy, who is herself one celestial magistrate among many.

The civic imagery of a res publica of the mind isn’t accidental, or just a rhetorical flourish to make Boethius feel less lonely. This community is ruled by reason, and submitting to its laws is freedom, which even at the individual level echoes the entire harmonious ordering of the cosmos. Once again, ancient and medieval audiences, who constantly associated the soul with cities, would have immediately understood this connection. This theme is echoed in Plato’s Republic and the tiers of souls, and in Renaissance humanists who saw the geometric outlines of cities as having symbolic significance.

Reason is the faculty which can apprehend Truth and align the soul towards its proper end. Ultimately, Lady Philosophy will re-teach Boethius that a Providential Divine Love rules and orders all things in the universe, and that governing the soul through Reason will bring it in harmony with Providence.8 Boethius’ original failure to do this was the source of his misery, which stemmed from placing his happiness in things subject to Fortuna (whom we still call “Lady Luck”).

This corrective process is clearest at the individual level of one soul reaching up to apprehend and harmonize with the Divine, but it’s also a civic and communal process, because the soul is a microcosm of the city, which is in turn a microcosm of the cosmos. And in fact, this adds a poignant layer of irony to Boethius’ wandering astray; distracted by his temporal citizenship as a Roman, he lost sight of his higher citizenship as a philosopher.

What then ought we to do with this vision of a Boethian civic-cosmos as it might relate to education? On one level, we might conclude that this is an interesting and elegant metaphor, is very helpful for understanding the pre-modern world, and leave it there. But in jumping to esoteric metaphors and models of the universe, we might overlook the very basic fact that this notion of a citizen body of philosophers simply…works. As in, it heals Boethius.

One cannot imagine Boethius being able to write The Consolation of Philosophy without either first overcoming the suffering and anguish of exile and imprisonment, or as the writing process being the cathartic exercise itself. Much of what makes imprisonment such a punishment in the first place is, along with the loss of liberty, the public shame and social isolation of being cut off from the world. Within a prison community, extra punishment is often doled out via solitary confinement. One of the greatest acts of charity is visiting the imprisoned.

Within Boethius’ isolation, however, Reason manifested itself as a condescending act of mercy and solace, in so doing restoring Boethius’ membership in another community, one not constrained by physical barriers. With his citizenship regained, Reason liberated Boethius to pursue his philosophical inquiry throughout the rest of the book. It’s fitting that, like so many other great works of classical philosophy, The Consolation is composed as a dialogue.

That is, a conversation.

All quotes from the Penguin Classics edition of The Consolation, translated by Victor Watts, copyright 1999. Quote from BK I, pg. 7.

Consolation, BK I, pg. 8

BK I, pg. 16.

BK I, pg. 17.

BK I, pg. 8.

BK I, pg. 5.

There are very clear parallels to Dante here, with Vergil and Beatrice.

The entire Divine Comedy leads up to this point, where Dante finally beholds the Beatific Vision which loves and orders all of Reality.